Abstract

Background. Endocan (endothelial cell-specific molecule-1) is a soluble dermatan sulfate proteoglycan of the extracellular matrix released into the circulation by vascular endothelial cells and involved in vascular processes in which endothelial cell activation occurs. In this study, we aimed to evaluate serum and urinary endocan levels in children with hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) during the acute disease and follow-up period, compared with controls, and to evaluate associated clinical and laboratory parameters.

Methods. Children were evaluated in three groups: HUS patients in the active stage (Group 1, HUS-active stage, n=15), HUS patients followed until the resolution of active disease (Group 2, HUS-follow-up, n=10) and healthy controls (Group 3, n=15). Clinical parameters and renal outcomes were compared between the groups based on serum and urinary endocan levels.

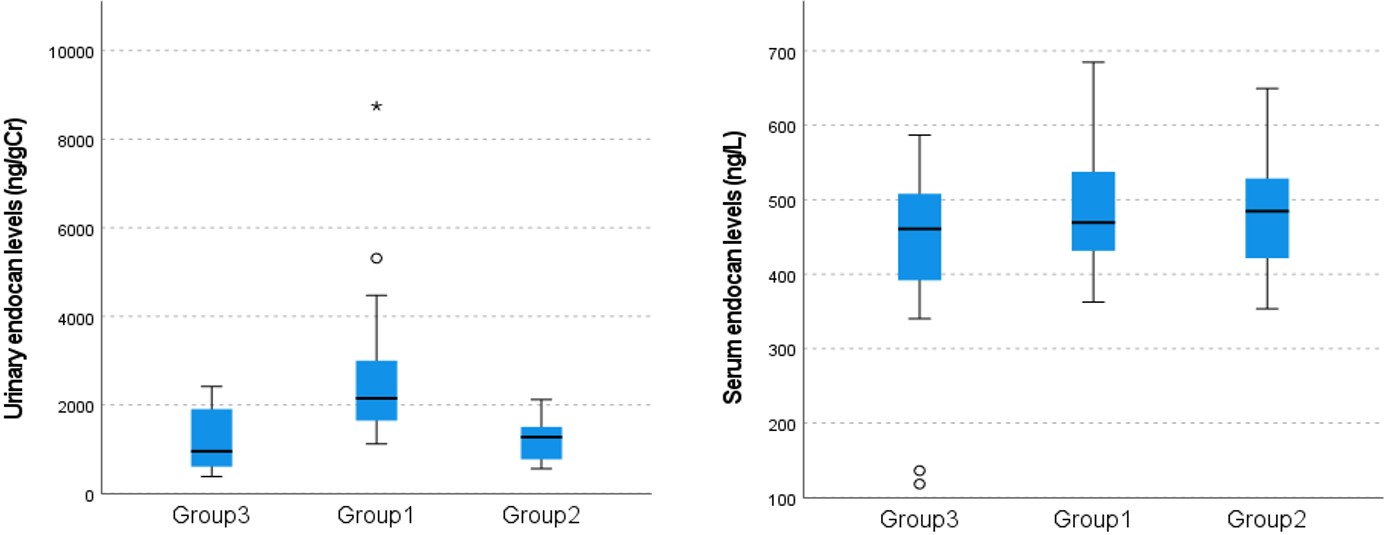

Results. The pairwise group comparisons of the urinary endocan levels (median; Q1-Q3) revealed statistically significant differences between Group 1 (2148; 1592-3068 ng/gCr) and Group 2 (1274; 733-1565 ng/gCr), and between Group 1 and Group 3 (954; 517-1966 ng/gCr) (P<0.01), but not between Group 2 and Group 3 (P>0.05). The serum endocan level showed no statistically significant difference between the groups (p>0.05). When all groups were evaluated together, urinary endocan level showed positive correlations with white blood cell counts (r= 0.63, P<0.001), and with lactic dehydrogenase (r= 0.51, P<0.001), blood urea nitrogen (r= 0.48, P<0.05) and serum creatinine levels (r= 0.50, P<0.001). However, urinary endocan levels showed negative correlations with hemoglobin (r= -0.57, P<0.001) and platelet levels (r= -0.37, P<0.05), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (r= -0.45, P<0.001). The urinary endocan levels of patients with HUS decreased significantly during follow-up (P<0.05).

Conclusions. Our findings suggested that urinary endocan levels were significantly elevated in HUS patients in the active stage. In addition, several important laboratory parameters in the HUS clinic were associated with urine endocan levels.

Keywords: hemolytic uremic syndrome; endocan; endothelial damage; children

Introduction

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is a thrombotic microangiopathy, and it is characterized by hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute kidney injury (AKI).1,2 It is more common in children under five years old, with an incidence of 5-6/100,000. In HUS, microthrombi formed due to vascular damage, causes platelet aggregation and ultimately leads to thrombocytopenia. At the same time, hemolytic anemia occurs with damage to erythrocytes as they pass through thrombosed vessels. These events result in ischemic organ damage, especially in the kidneys. HUS presents with general disease symptoms, hematological findings, signs of AKI and extrarenal findings such as seizures, colitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, elevated liver enzymes, and myocardial dysfunction.2 In 2016, the International Consensus proposed a new classification system for HUS.3

Endocan (endothelial cell-specific molecule-1) is a 50-kDa soluble proteoglycan consisting of dermatan sulfate and a mature polypeptide of 165 amino acids.4,5 It is expressed in vascular endothelial cells, pulmonary capillaries, kidneys (glomerular endothelial cells and tubular epithelial), cardiomyocytes, digestive system, liver, brain, thyroid gland, thymus, epididymis, skin, and lymph nodes.6,7 Endocan is involved in various vascular processes that regulate endothelial activation, endothelial permeability, and cellular adhesion and proliferation.8 Endocan may be an independent predictor or a new prognostic biomarker in immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy7 cardiovascular events due to chronic kidney disease (CKD)9, chronic renal allograft injury10, coronary artery diseases11, cancers12 and diabetic nephropathy.13 Although endocan is present in extremely low concentrations in body fluids, it can be easily detected due to its stability in physiological conditions. Therefore, it can be a non-invasive diagnostic and prognostic marker in various systemic and renal diseases.4

Developing clinical prediction scores and rapid diagnostic tools is essential for early identification of patients with HUS and timely initiation of targeted therapies.² However, to date, no specific biomarker has been identified that can guide hospitalization decisions or reliably assess disease severity in children with HUS. Although endocan is associated with many diseases, no study has evaluated its relationship with HUS. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate serum and urinary endocan levels in children with HUS during the acute disease and follow-up period, compared to controls; and to evaluate associated clinical and laboratory parameters.

Material and Methods

Patients and study design

This study was prospectively conducted in the pediatric nephrology clinic of Atatürk University Faculty of Medicine in 2021 and 2022. Pediatric patients included in the study were evaluated in three groups: a) HUS patients in active stage (Group 1, HUS-active stage, n=15), b) HUS patients who could be followed until the resolution of active disease (Group 2, HUS-follow-up, n=10) and c) healthy controls (Group 3, n=15). The patients’ age, sex, weight, and vital signs were recorded. Hematological and biochemical tests were performed. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Schwartz formula.14 AKI was staged according to the KDIGO study.15 The diagnosis of HUS was based on the presence of the triad of renal dysfunction showing an elevated serum creatinine level for age and height, hemolytic anemia (hemoglobin <8 g/dL or hematocrit <30%), and thrombocytopenia (platelet count <150x109/L).2

The clinical severity of HUS was evaluated on the following six items, with a score assigned to each item: 1) Prolonged anuria (longer than two weeks); 2) Kidney replacement therapy (KRT) requirement; 3) KRT lasting longer than four weeks; 4) Diagnosis of atypical HUS (aHUS), Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome (SP-HUS), cobalamin C-HUS, or atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) with diacylglycerol kinase epsilon (DGKE) gene variant; 5) Stage 3 AKI in the acute phase of the disease; and 6) Non-renal organ involvement (pancreatitis, elevated liver enzymes, colitis, cholecystitis, myocardial dysfunction, rhabdomyolysis, ulcerative-necrotic skin lesions, seizure, lethargy, and coma).1,2 Urinary blood and protein measurements were performed semi-quantitatively using the photometric method in a fully automated H-800 Dirui urine analyzer (DIRUI, H-800, China). The patients were treated following the most recent guidelines and discharged from the hospital upon clinical improvement.2,16,17

Sample collection and storage

Blood and urine samples were collected from all patients: Group 1 within the first 48 hours of admission (mean: 2.0±0.3 days), Group 2 during follow-up (mean: 2.2±0.7 months after the first admission), and Group 3 during the whole study period. Blood samples (3.5 mL) were collected into biochemistry tubes, and urine samples (5 mL) were collected into sterile urine tubes. The blood samples were kept at room temperature for 20 minutes, and then centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 15 minutes. Serum samples obtained after centrifugation were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and aliquoted. The urine samples were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 15 minutes, and then the supernatant was transferred to microcentrifuge tubes and aliquoted. The aliquoted serum and urine samples were stored in an ultra-low temperature freezer at -80 °C until the study day.

Analyte assay techniques

For the measurement of serum and urine endocan levels, the BT LAB enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Bioassay Technology Laboratory, Cat. No. E3160Hu, lot no. 202205005, China) was used. The experimental steps in the kit insert were applied to the automatic ELISA reader device, and the samples were analyzed with the ELISA method using the automatic Dynex ELISA reader device (Dynex Technologies Headquarters, Chantilly, USA). The results were expressed as ng/L. The sensitivity of the ELISA kit was 2.56 ng/L, and its detection range was 5-2,000 ng/L. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were below 4% and 10%, respectively. Urine creatinine levels were determined through the kinetic colorimetric measurement using the Jaffe method on the Roche Cobas c702 device (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Urine creatinine was measured in the same urine specimens. The urine endocan level was expressed relative to the creatinine concentration: endocan/creatinine (ng/gCr).

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS v. 25.0 for Windows software (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The chi-square test was used to assess the sex distribution among the study groups. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine the normality of the data. For nonparametric data, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the means and medians of two groups. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare group means. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Duncan or Kruskal-Wallis tests (adjusted by the Bonferroni correction). The Spearman rho correlation test was applied to evaluate relationships among all continuous variables, both across the total sample and within groups. The results are shown as mean ± standard deviation or median (Q1-Q3), depending on data distribution. An alpha significance level of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics committee approval

This study was conducted after receiving ethical approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Atatürk University Faculty of Medicine (2021/06-55). Written consent was obtained from the parents of the patients/healthy controls.

Results

All Group 1 patients had clinical and laboratory findings consistent with HUS. Hemoglobin (Hb) and serum endocan levels were normally distributed (P>0.05), whereas the other analyzed characteristics were not (P<0.01). The demographic characteristics and the blood and urine results of the groups are given in Table I. The pairwise group comparisons of median urinary endocan levels revealed significant differences (P<0.01) between Group 1 and Group 2, and between Group 1 and Group 3, but not between Group 2 and Group 3 (P>0.05). Although the mean serum endocan level was higher in Group 1, the difference between groups was not statistically significant. (P>0.05) (Table I, Fig. 1). There was also no significant correlation between the serum endocan levels and urinary endocan levels in all groups (r=0.29, P>0.05)

|

Data are presented as n (%), mean±SD or median (Q1-Q3). a,bThe difference between means/medians with the same letter is not significant, but the difference between means/medians with different letters is significant. BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; SD, standard deviation; Q1, 25th percentile; Q3, 75th percentile; WBC, white blood cell. |

||||

| Table I. Demographic characteristics and laboratory findings of the study groups. | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (month) |

|

|

|

|

| Body weight (kg) |

|

|

|

|

| Female sex |

|

|

|

|

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) |

|

|

|

|

| WBC (N: 4.5–13.5 ×103μL) |

|

|

|

|

| Hemoglobin (N: 12–16 g/dL) |

|

|

|

|

| Platelet (N: 150–450 x103/μL) |

|

|

|

|

| LDH (N: < 248 U/L) |

|

|

|

|

| BUN (N: 7-17 mg/dL) |

|

|

|

|

| Cr (N: 0.4-1.2 mg/dL) |

|

|

|

|

| Serum endocan (ng/L) |

|

|

|

|

| Urinary endocan (ng/gCr) |

|

|

|

|

Most of the laboratory parameters in Group 1 differed significantly from those in the other groups (Table I). When all groups are evaluated together, the mean urinary endocan level positively correlated with most laboratory parameters (Table II). In Group 1, the serum and urinary endocan levels did not show a statistically significant correlation with the clinical severity score (r= 0.16, P=0.117; and r= 0.05, P=863), hypertension (r= -0.03, P=0.908; r= 0.36, P=0.187), urine protein (r= 0.32, P=0.250; and r= -0.19, P=0.497) and urine blood positivity (r= 0.40, P=0.143; and r= -0.23, P=0.408), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (r= 0.31, P=0.417; r= 0.05, P=0.898), C-reactive protein (CRP, r= -0.46, P=0.117; r= 0.05, P=0.972), respectively. Distribution of the clinical severity score and AKI stages of patients in Group 1 (n=15) is presented in Table III. In Group 1, patients with stage III AKI had a significantly higher mean serum endocan level (546.2±89.32 ng/L), when compared to Group 1 patients with stage I (363.3±1.20 ng/L) and stage II (419.3±28.38 (ng/L) AKI (P<0.05). No statistically significant difference was observed between urinary endocan levels according to AKI stages (P>0.05) (Table III). When Group 1 patients with (n=5) and without (n=10) hypertension were compared, there was no statistical difference in terms of serum (means±SD: 496.2±97.48 vs. 496.5±112.28 ng/L, P=0.953) and urine (medians [Q1-Q3]: 2238.2 [2005.8-4891.9] vs. 1767.4 [1399.8-2965.9] ng/gCr; P=0.206) endocan levels. There was no significant difference in serum (means±SD: 506.0±78.09 vs. 485.4±133.67 ng/L; P=0.463) and urinary (medians [Q1-Q3]; 1644.7 [1307.2-2837.8] vs. 2274.4 [1863.6-4471.9] ng/gCr; P=0.094) endocan levels in patients who needed KRT compared to those who did not need KRT.

| *: P<0.05, **: P<0.01. AKI, acute kidney injury; Cr, creatinine. | ||

| Table II. Correlation coefficients and significance levels in the parameters analyzed in the study groups. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

| General | ||

| White blood cell count |

|

|

| Hemoglobin level |

|

|

| Platelet count |

|

|

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

|

|

| Serum creatinine level |

|

|

| Blood urea nitrogen level |

|

|

| Lactate dehydrogenase level |

|

|

| Group 1 | ||

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

|

|

| Stage of AKI in the acute phase of the disease |

|

|

| Group 2 | ||

| The time taken until urine sample collection |

|

|

| Group 3 | ||

| White blood cell count |

|

|

| Serum endocan level |

|

|

|

a,bWhile there is no significant difference between the means indicated with the same letter, there is a significant difference between the means indicated with different letters. *P<0.05 &Patients received 1 point for each present parameter, and the clinical severity score was determined by summing all scores. AKI, acute kidney injury; HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; SD, standard deviation. |

|||||

| Table III. Distribution of Group 1 (n=15) patients in terms of clinical severity score and AKI stage. | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Acute kidney injury | Stage I |

|

|

|

|

| Stage II |

|

|

|

|

|

| Stage III |

|

|

|

|

|

| Parameters of clinical severity& | Stage III AKI in the acute phase of the disease |

|

|

||

| KRT requirement |

|

|

|||

| Diagnosis of atypical HUS |

|

|

|||

| Anuria > 2 weeks |

|

|

|||

| Non-renal organ involvement |

|

|

|||

| KRT > 4 weeks |

|

|

|||

| Clinical severity score | Score 0 |

|

|

||

| Score 1 |

|

|

|||

| Score 2 |

|

|

|||

| Score 3 |

|

|

|||

| Score 4 |

|

|

|||

| Score 5 |

|

|

|||

Discussion

HUS is a thrombotic microangiopathy characterized by thrombocytopenia, intravascular hemolysis and AKI.18 Although HUS has various etiological causes, including environmental triggers or genetic mutations, all forms of HUS present with endothelial damage, in which there are microvascular lesions characterized by the formation of fibrin and platelet-rich thrombi.2 Non-invasive diagnosis of various kidney diseases remains a challenge in clinical practice. Blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine levels and proteinuria are the commonly practiced diagnostic parameters to evaluate kidney pathologies; however, they are not specific.4 The diagnostic methods for AKI due to many causes, including HUS, are mainly based on serum creatinine measurement. However, the decreased sensitivity and specificity of this marker, which does not always reflect the extent of renal parenchymal destruction, has led to the evaluation of alternative markers associated with inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, such as endocan.19

In the current study, although the mean serum endocan level was higher in Group 1, mean serum endocan levels showed no statistically significant difference between the groups (P>0.05). However, the mean urinary endocan level in Group 1 patients was significantly higher than in the other groups (P<0.05). Our findings suggest that urinary endocan levels may provide more valuable information than serum endocan levels in patients diagnosed with HUS. Also, higher urine endocan levels may indicate the active stage of the disease.

There is limited data on the metabolism and excretion of circulating endocan. Normally, endocan cannot pass through the negatively charged basement membrane in a healthy glomerulus, due to the presence of highly negatively charged dermatan sulfate, an essential component of endocan.7 It is unclear whether the increase in serum endocan levels in renal diseases is due to increased production or decreased renal clearance. In addition, it remains unclear whether the increase in urinary endocan levels results from the release of this molecule from damaged renal tubular cells or from its leakage from plasma due to an impaired glomerular basement membrane.4,9 In the literature, studies investigating serum endocan levels are more common than those investigating urinary endocan levels. In these studies, serum endocan levels were found to be significantly higher in many diseases.7,9-11,13,19-24 In our study, urinary endocan levels were significantly higher in patients with HUS. This finding suggests that endocan release into the urine may differ from endocan release into the circulation due to impaired glomerular permeability caused by endothelial damage in HUS.

Lee et al.7 found that serum and urinary endocan levels were higher in adult patients with IGA nephropathy than in healthy controls. In the same study, plasma endocan levels did not differ significantly across CKD stages. However, patients with higher serum endocan levels had unfavorable renal outcomes. Urinary endocan levels were also higher in patients with poor renal function. In another study of adult patients, plasma endocan concentrations were significantly higher in CKD patients than in controls. They became progressively higher throughout the CKD stages. Plasma endocan concentrations were negatively correlated with eGFR and positively correlated with high-sensitivity CRP.9 As we did not have any patient with CKD as a result of HUS, we could not make an evaluation to determine the relation of endocan and the presence of CKD in children with HUS.

Since inflammation and endothelial dysfunction are involved in the pathogenesis of AKI, it has been assumed that elevated serum endocan levels may reflect renal dysfunction in this patient group.4 In our study, stage III AKI was detected in 10 of 15 patients in Group 1. The mean serum endocan level was significantly higher in 10 patients with AKI III than in the other five patients with AKI I and II (P<0.05). Furthermore, serum endocan levels were positively correlated with AKI stages (r=0.59, P<0.05). This finding suggests that serum endocan level may be used to determine patients with high AKI stage during the active stage of HUS.

Rahmania et al.24 evaluated the predictive value of endocan in the requirement of KRT in a group of intensive care patients with AKI. They found higher serum endocan and creatinine levels in those who required RRT. In our study, KRT was needed in 8 of 15 patients in the active disease group (Group 1). There was no significant difference in serum and urinary endocan levels between the patients who needed KRT and those who did not. This difference may result from the sample differences since our sample did not include KRT patients requiring intensive care.

In Group 1, the serum and urinary endocan levels did not show a statistically significant correlation with the clinical severity score (P>0.05). These findings may be explained by the small number of patients included in the study and the low mean clinical severity score (2.20±1.56) in Group 1.

The clinical diagnosis of HUS is based on the triad of anemia (hemoglobin <8 g/dL), thrombocytopenia (platelets < 150 × 109/L), renal dysfunction, including hematuria, proteinuria, and an elevated serum Cr level.25 Elevated white blood cell (WBC) count (greater than 20,000 per mm3), and hematocrit (greater than 23%) are other risk factors for mortality and long-term complications from HUS.26 In our study, when all groups were analyzed together, mean urinary endocan levels showed significant positive correlations with WBC count, and with lactate dehydrogenase, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine levels, and significant negative correlations with hemoglobin level, platelet count, and eGFR. Taken together, these findings indicate that several key laboratory parameters relevant to the diagnosis and follow-up of HUS are closely associated with urinary endocan levels.

This study has certain limitations. One significant limitation is the small sample size, which was a result of the rarity of HUS cases. Therefore, larger-scale, multicenter clinical studies are needed to provide more meaningful insights into the applicability of endocan as a marker in the diagnosis, follow-up and prognosis of HUS patients.

In conclusion, urinary endocan levels were significantly higher in HUS patients in the active phase. The urinary endocan level may provide more valuable information than the serum endocan level in the clinical follow-up of patients with HUS. Also, serum endocan level may be used to evaluate AKI level during the active stage of HUS. We believe this study will guide future research investigating the long-term prognostic value of endocan in patients with HUS and exploring its potential as a target marker for the treatment and diagnosis of HUS.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Atatürk University Faculty of Medicine (date: September 30, 2021, number: 2021/06-55). Written consent was obtained from the parents of the patients and healthy controls.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Cody EM, Dixon BP. Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am 2019; 66: 235-246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2018.09.011

- Manrique-Caballero CL, Peerapornratana S, Formeck C, Del Rio-Pertuz G, Gomez Danies H, Kellum JA. Typical and Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome in the Critically Ill. Crit Care Clin 2020; 36: 333-356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2019.11.004

- Loirat C, Fakhouri F, Ariceta G, et al. An international consensus approach to the management of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in children. Pediatr Nephrol 2016; 31: 15-39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-015-3076-8

- Nalewajska M, Gurazda K, Marchelek-Myśliwiec M, Pawlik A, Dziedziejko V. The Role of Endocan in Selected Kidney Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21: 6119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176119

- Sarrazin S, Adam E, Lyon M, et al. Endocan or endothelial cell specific molecule-1 (ESM-1): a potential novel endothelial cell marker and a new target for cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006; 1765: 25-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2005.08.004

- Zhang SM, Zuo L, Zhou Q, et al. Expression and distribution of endocan in human tissues. Biotech Histochem 2012; 87: 172-178. https://doi.org/10.3109/10520295.2011.577754

- Lee YH, Kim JS, Kim SY, et al. Plasma endocan level and prognosis of immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2016; 35: 152-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.krcp.2016.07.001

- Leite AR, Borges-Canha M, Cardoso R, Neves JS, Castro-Ferreira R, Leite-Moreira A. Novel Biomarkers for Evaluation of Endothelial Dysfunction. Angiology 2020; 71: 397-410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319720903586

- Yilmaz MI, Siriopol D, Saglam M, et al. Plasma endocan levels associate with inflammation, vascular abnormalities, cardiovascular events, and survival in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2014; 86: 1213-1220. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2014.227

- Su YH, Shu KH, Hu CP, et al. Serum Endocan correlated with stage of chronic kidney disease and deterioration in renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 2014; 46: 323-327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.10.057

- Çimen T, Efe TH, Akyel A, et al. Human Endothelial Cell-Specific Molecule-1 (Endocan) and Coronary Artery Disease and Microvascular Angina. Angiology 2016; 67: 846-853. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319715625827

- Huang X, Chen C, Wang X, et al. Prognostic value of endocan expression in cancers: evidence from meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther 2016; 9: 6297-6304. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S110295

- Lv Y, Zhang Y, Shi W, et al. The Association Between Endocan Levels and Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Am J Med Sci 2017; 353: 433-438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjms.2017.02.004

- Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, et al. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20: 629-637. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2008030287

- Kellum JA, Lameire N, Aspelin P, et al. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2012; 2: 1-138. https://doi.org/10.1038/kisup.2012.2

- Igarashi T, Ito S, Sako M, et al. Guidelines for the management and investigation of hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin Exp Nephrol 2014; 18: 525-557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-014-0995-9

- Sheerin NS, Glover E. Haemolytic uremic syndrome: diagnosis and management. F1000Res 2019; 8: F1000 Faculty Rev-F1000 Faculty1690. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.19957.1

- Jokiranta TS. HUS and atypical HUS. Blood 2017; 129: 2847-2856. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-11-709865

- Samouilidou E, Athanasiadou V, Grapsa E. Prognostic and Diagnostic Value of Endocan in Kidney Diseases. Int J Nephrol 2022; 2022: 3861092. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3861092

- Azimi A. Could “calprotectin” and “endocan” serve as “Troponin of Nephrologists”? Med Hypotheses 2017; 99: 29-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2016.12.008

- Raptis V, Bakogiannis C, Loutradis C, et al. Levels of Endocan, Angiopoietin-2, and Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1a in Patients with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease and Different Levels of Renal Function. Am J Nephrol 2018; 47: 231-238. https://doi.org/10.1159/000488115

- Samouilidou E, Bountou E, Papandroulaki F, Papamanolis M, Papakostas D, Grapsa E. Serum Endocan Levels are Associated With Paraoxonase 1 Concentration in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. Ther Apher Dial 2018; 22: 325-331. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-9987.12654

- Oka S, Obata Y, Sato S, et al. Serum Endocan as a Predictive Marker for Decreased Urine Volume in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. Med Sci Monit 2017; 23: 1464-1470. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.900693

- Rahmania L, Orbegozo Cortés D, Irazabal M, et al. Elevated endocan levels are associated with development of renal failure in ARDS patients. Intensive Care Med Exp 2015; 3(Suppl 1): A264. https://doi.org/10.1186/2197-425X-3-S1-A264

- Liu Y, Thaker H, Wang C, Xu Z, Dong M. Diagnosis and Treatment for Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Associated Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Toxins (Basel) 2022; 15: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins15010010

- Boyer O, Niaudet P. Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome in Children. Pediatr Clin North Am 2022; 69: 1181-1197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2022.07.006

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.