Graphical Abstract

Abstract

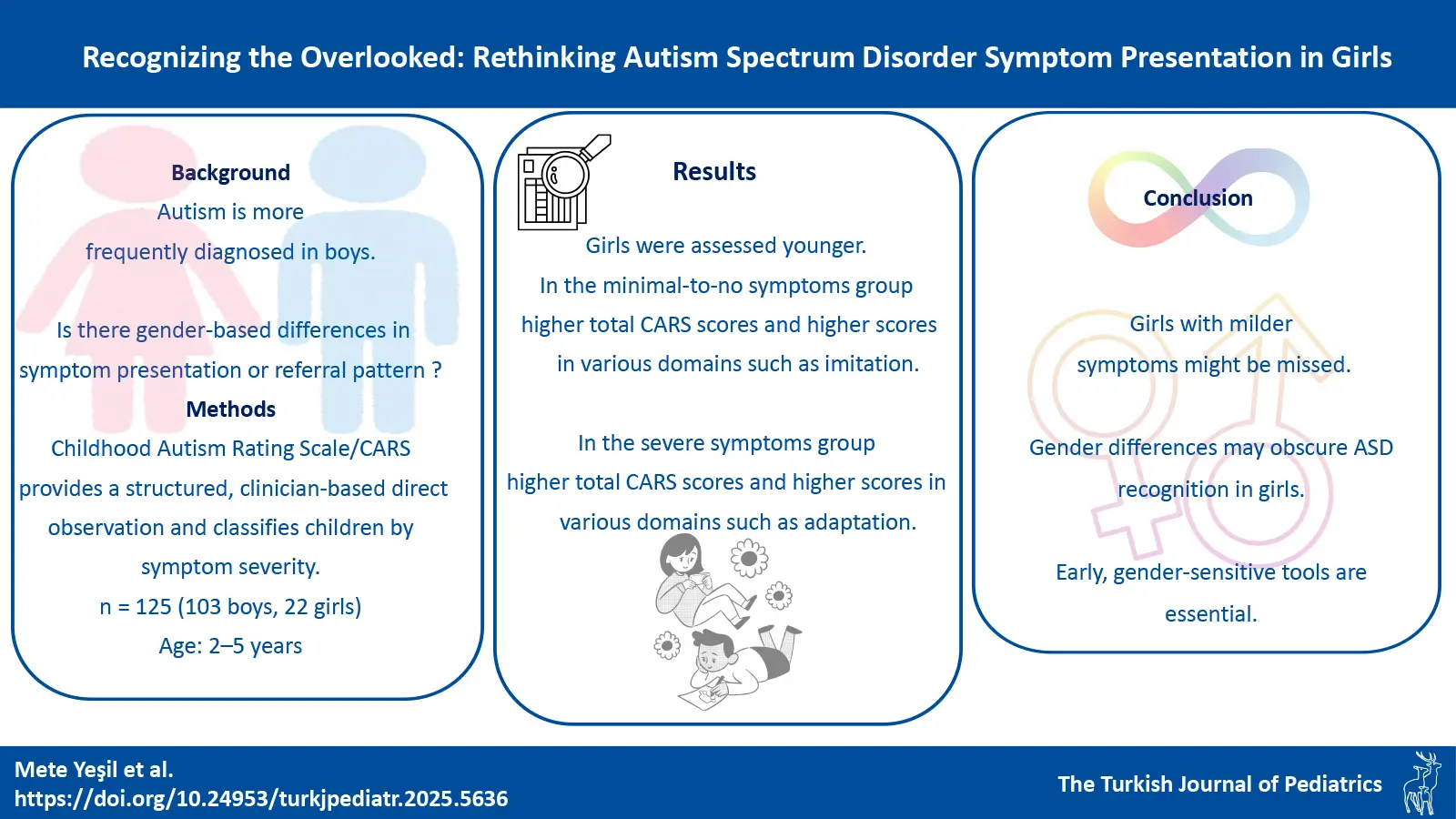

Background. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is more frequently diagnosed in boys than in girls, possibly due to gender-based differences in symptom presentation or referral patterns. This study investigates gender-related variations in symptom severity and clinical presentation among preschool children referred for suspected ASD.

Methods. This study included 125 children (boys: n=103; girls: n=22) aged 2–5 years suspected of having ASD. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) was used to evaluate autism-related symptoms, focusing on presenting complaints and gender-specific differences in nonverbal communication and social interaction.

Results. Girls had a significantly younger median age at assessment (28 months) compared to boys (33 months, p=0.03). In the minimal to no symptoms group, girls had significantly higher total CARS scores (median 26 vs. 22.5, p < 0.001) and elevated ratings in domains such as nonverbal communication (p=0.03), relationship to people (p=0.01), imitation (p < 0.001), and visual response (p < 0.001). In the severe group, girls also showed significantly higher scores in adaptation to change, taste, smel, and touch response and use, and fear or nervousness. Effect sizes ranged from small to strong. A negative correlation was found between assessment age and total CARS score (r= –0.45, p < 0.01), particularly among girls.

Conclusion. This study highlights that girls may exhibit more prominent symptoms by the time they are referred for clinical evaluation, raising concerns about missed or delayed recognition of milder symptom profiles.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, sex characteristics, female, child, preschool, diagnosis

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is an early-onset neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by difficulties in social interaction and communication skills, as well as restricted and repetitive behaviors.1 In recent years, the prevalence of autism has significantly increased, based on data from 2016, ASD prevalence estimates stand at 18.5 per 1000 (1 in 54) children by the age of 8, with rates among boys being 4.3 times higher than among girls.2

The difference in prevalence between boys and girls may be attributed to factors such as gender bias in diagnosis or genuinely better adaptation/compensation in girls. Considering that diagnosis heavily relies on a comprehensive assessment of personal history and direct observation of behaviors, and early diagnosis and intervention are critical in autism, the disproportionate diagnosis in males compared to females emerges as an issue warranting closer scrutiny. Several hypotheses have been formulated to explore whether male-specific risk factors and female-specific protective factors underlie this bias. However, it is important to note that the male risk and female protective factors are not mutually exclusive. It is suggested that both may contribute to the discrepancy observed in ASD diagnosis.3 Research indicates that a greater number of concurrent behavioral or cognitive difficulties may need to be present in girls for the disorder to be identified.4 While in girls, ASD incidence remained low until age 10, then increased, peaking in early adolescence; for boys, incidence sharply increased from birth, peaking at age 4, remaining steady until age 15, then declining. It is also supported by some evidence that adult women are seeking and receiving autism diagnoses to a greater extent than men.5,6 It is possible that females have been even more disregarded at a younger age compared to their male counterparts, and indeed, current evidence supports the existence of a “female-typical autism presentation”.4 Understanding how sex and gender affect clinical presentation, biology, developmental trajectory, and treatment response is not only crucial for accurate diagnostic assessment but also effective intervention planning, and promoting societal gender equity.7

While recent literature increasingly addresses gender differences in autism, there remains a critical gap in identifying the more subtle and subthreshold symptom presentations often observed in girls. These may include milder or masked social communication difficulties and fewer observable restricted behaviors, particularly during early childhood.8,9 Such nuanced presentations may not meet the conventional diagnostic threshold, yet still cause functional impairment and delay in intervention.4,10 Standardized diagnostic tools, predominantly validated in male populations, may overlook these less overt manifestations, contributing to the underrecognition of ASD in females.

In this study, our aim was to investigate whether there were gender-related differences in the presenting complaints and observational assessments using standard measures among children suspected of having ASD, including those with subtle symptoms, given the critical importance of early diagnosis. We hypothesized that symptom severity and presentation patterns would differ between girls and boys, particularly across ASD severity strata, as measured by item-level scores on a standardized assessment.

Materials and Methods

To investigate sex differences in core symptoms and referral characteristics of ASD, we enrolled children with suspected ASD who were assessed using the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hacettepe University, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants and study procedure

The target population of the study consisted of children who were assessed using the CARS. These children had initially been referred to the Division of Developmental Pediatrics by general pediatricians or family physicians. In our division, developmental pediatricians perform the initial clinical evaluation using a structured form that encompasses detailed information on developmental milestones, behavioral concerns, and family observations. Following this evaluation, the CARS is administered to children for whom autism-related signs or parental concerns raise suspicion of ASD. In this context, children aged 24-60 months who were evaluated using CARS at the Hacettepe University İhsan Doğramacı Children’s Hospital, Division of Developmental Pediatrics between December 2020 and December 2023 were included in the study, The exclusion criteria included: (1) a history of receiving special education for more than one month, (2) a history of other neurological or genetic disorders, such as Rett syndrome, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, or severe head injury, (3) hearing or visual impairment.

The participants’ basic sociodemographic data, presenting complaints, and CARS scores were obtained retrospectively from the patient records. The CARS assessment is based on inter-rater agreement between two observers, who evaluate the child–caregiver dyad through a mirrored playroom and also engage directly with the child and caregiver through structured interaction and interview. This scale was developed in 1971 by Schopler and Reichler to diagnose and assess autism. This scale consists of 15 items and is completed by clinicians based on interviews with families, gathering information from relevant individuals, and observing the child. The items include relationship to people, imitation, emotional response, body use, object use, adaptation to change, visual response, listening response, taste, smell, and touch response and use, fear or nervousness, verbal communication, nonverbal communication, activity level, level and consistency of intellectual response, and general impressions. A total score on the scale ranging from 30 to 36.5 indicates mild-to-moderate autism, while a score between 37 and 60 indicates severe autism. The validity and reliability study of the Turkish version was conducted.11,12

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 19.0 software (SPSS Inc). The normality of continuous data was assessed using both statistical tests and visual methods such as histograms and Q-Q plots. Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables are summarized using numbers and percentages. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Differences in continuous variables among independent groups were assessed using the independent samples t-test for two groups. The Mann-Whitney U test compared continuous variables that were not normally distributed. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient evaluated correlations between non-normally distributed variables. A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The study included 125 patients. Table I presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants, showing no significant differences between girls (n=22) and boys (n=103) in terms of gestational age, maternal age, and paternal age. However, there was a statistically significant difference in the assessment age (p=0.03), with girls having a median age of 28 months and boys 33 months. Other factors, such as maternal and paternal education levels, and birth order, were similarly distributed between genders.

|

*p < 0.05. Statistical tests: Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparisons of non-normally distributed continuous variables (assessment age and gestational age). Independent samples t-test was used for normally distributed continuous variables (maternal and paternal age). Categorical variables (parental education, birth order) were compared using chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. Effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d for parametric comparisons and r for non-parametric tests. Effect sizes are reported as r for non-parametric tests, Cohen’s d for parametric comparisons, and Cramér’s V for categorical variables. IQR: interquartile range, SD: standard deviation. |

|||||

| Table I. Basic sociodemographic characteristics. | |||||

| Variable |

|

|

|

|

|

| Assessment age (months); median (IQR) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gestational age (weeks), median (IQR) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Maternal age (years), mean ± SD |

|

|

|

|

|

| Maternal education, n (%) |

|

|

|||

| < High school |

|

|

|

||

| ≥ High school |

|

|

|

||

| Paternal age (years), mean ± SD |

|

|

|

|

|

| Paternal education, n (%) |

|

|

|||

| < High school |

|

|

|

||

| ≥ High school |

|

|

|

||

| Birth order, n (%) |

|

|

|||

| First |

|

|

|

||

| Second |

|

|

|

||

| Others |

|

|

|

||

Speech delay was the primary complaint in 95.2% of girls (n=20) and 81.6% of boys (n=84), with no significant difference between groups. Non-response to name was reported as the main complaint in 9.8% of all cases (n=12), while lack of eye contact appeared as the primary complaint in 7.4% (n=9), with no significant difference observed based on gender (p > 0.05).

Among the girls who participated in the study, 50% (n=11) and 51.5% (n=53) of the boys had minimal to no symptoms of ASD according to CARS. There was no significant gender difference in the ASD severity group distributions (p>0.05, Table II).

|

*p<0.05. Data presented as median (interquartile range). All comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test due to the small sample sizes and non-normal distribution of the data. Effect sizes are reported as r. CARS: Childhood Autism Rating Scale. |

||||||||||||

| Table II. Autism spectrum disorder related symptoms according to gender and severity of autism. | ||||||||||||

|

(CARS score 15-29.5) |

(CARS score 30-36.5) |

(CARS score 37-60) |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Assessment age (months) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CARS Scores | ||||||||||||

| 1. Relationship to people |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Imitation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Emotional response |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. Body use |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5. Object use |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6. Adaptation to change |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7. Visual response |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 8. Listening response |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 9. Taste, smell, and touch response and use |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 10. Fear and nervousness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 11. Verbal communication |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 12. Nonverbal communication |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 13.Activity level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 14.Level and consistency of intellectual response |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 15. General impressions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total Scores |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When evaluating autism symptoms according to severity and gender, it was found that in the group with minimal to no symptoms of ASD, the median total CARS score for girls was significantly higher than that for boys (26 vs. 22.5; p=0.00), with a large effect size (r=0.819). The median assessment age for girls in this group was also significantly lower (28 vs. 34 months; p=0.02). Girls showed significantly higher scores on CARS items 1, 2, and 7, with moderate to strong effect sizes (r=0.524, 0.404, and 0.394, respectively). Although not all comparisons reached statistical significance, items 5, 8, and 12 also demonstrated moderate effect sizes, suggesting meaningful differences. Furthermore, correlation analyses revealed that younger assessment age was associated with higher scores on items 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 12, and 15, as well as the total CARS score (r= –0.37, –0.41, –0.30, –0.34, –0.27, –0.34, –0.32, –0.45 respectively; p < 0.05). Similarly, among girls with severe symptoms, it was noted that their scores on items 6, 9, 10, and total scores of the CARS were significantly higher than those of boys. These differences had small to moderate effect sizes (r=0.25–0.31, Table II).

Discussion

During toddlerhood, the earliest stage for diagnosing autism in children, understanding gender differences is crucial.13 In this study, children aged 2-5 years who were suspected of having ASD based on parental concern and clinical observation were systematically evaluated, and it was found that some autism symptom scores were found to be higher in girls across varying severity levels, with different symptoms being more pronounced in each group. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate gender-related symptom differences assessed via the CARS in a preschool-aged clinical population in Türkiye.

There is conflicting evidence regarding whether boys and girls with ASD exhibit differences in symptom severity. Cognitive differences may complicate the comparison of symptoms since symptom severity often correlates with impairment levels. Despite controlling for IQ, studies have produced inconsistent results. While some research indicates similar scores in observational assessments, other studies have identified sex-related differences in ASD symptom severity and profiles, even when IQ is accounted for.14 In this study, girls in both the minimal to no symptoms group and the severe symptoms group had significantly higher total scores than boys, while no significant difference was observed in the moderate symptom group.

When examining gender differences in ASD symptoms, communication skills emerge as one of the most notable areas of difference. While typically developing girls have been shown to have better early communication skills, such as better receptive language skills and using more words for communication compared to boys during the infant period, this slight advantage isn’t observed in the ASD group.15 During the toddlerhood period, studies have reported variable results depending on whether they rely on observational data or parent reports. While parents often report that girls with ASD reach language milestones earlier, findings from direct clinical measurements of language in children diagnosed during toddlerhood demonstrate similar or worse linguistic and verbal abilities compared to boys. Additionally, it has been shown that the acquisition of gestures and pragmatics was more impaired in the female subgroup than in the male subgroup of children with ASD, aged between 2 and 7 years old.16 In our study, the finding that the nonverbal communication scores of girls were higher than those of boys in the minimal to no symptoms of ASD group not only aligns with the literature but also points to a very important and distinct aspect. Given that girls are generally expected to perform better in communication domains, the fact that those who did seek hospital evaluation still exhibited higher symptom scores may indicate a selection bias.

Another significant symptom domain believed to vary by gender notable findings concerns repetitive and restrictive behaviors. While data suggest a higher prevalence of these behaviors in males among older age groups, studies similar to ours have reported no significant gender differences in children under six years of age.17 Conversely, data from the Autism Treatment Network suggest that females under six years old, with at least average IQ, do not consistently display significantly fewer stereotyped behaviors compared to their male counterparts.18 The tendency for girls to engage in gender-typical play may lead to these behaviors being overlooked in girls during toddlerhood.19

Girls are often diagnosed later and at lower rates than boys, and some studies suggest that they may exhibit more complex or subtle social communication profiles.13 In our data, girls with minimal to no symptoms scored higher than boys in several areas including nonverbal communication, relationship to people, imitation, and visual response. This observation suggests that girls with subtler symptoms — who may still be experiencing challenges — might not have been referred for clinical assessment at all, potentially representing only the tip of the iceberg. While our findings are preliminary and limited to a small clinical sample, they align with this perspective and may contribute to a better understanding of gender-related presentation differences. These observations highlight the need for future research on the development of diagnostic tools that are better attuned to gender-related nuances.

This study is particularly valuable as it includes a detailed assessment of subthreshold ASD symptoms in girls. It provides a structured comparison across symptom severity levels and incorporates item-level analysis using standardized tools, which strengthens the internal consistency of findings. Moreover, it is one of the few studies focusing on early clinical presentation in a preschool-aged sample, a period when timely recognition is especially critical for developmental outcomes. Studies from Turkey specifically investigating gender-related symptom differences in early childhood autism remain scarce. One early study compared clinical features of autistic girls and boys and suggested that girls may present with distinct symptom profiles, but national literature has offered limited updates since. Our findings aim to contribute updated and contextually relevant evidence to this underexplored area.20

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample consisted of clinically referred children, which limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader population. In the minimal to no symptoms group, girls had a younger median age, and there was a negative correlation between age and symptom severity, suggesting the need for further analysis. Although girls in this group were significantly younger at the time of assessment, this may reflect earlier referral due to more overt concerns rather than underrecognition. However, this pattern may also mask the risk that girls with milder symptom profiles are overlooked entirely, a possibility that underscores the complexity of interpreting gender-related diagnostic trends. Due to the small sample size and non-normal distribution, advanced statistical tests could not be performed. Although the CARS is a widely used and validated tool, it may not be sensitive enough to detect mild or subtle symptoms, especially in girls. Additionally, other standardized diagnostic instruments were not available in our clinic during the study period, which limits the assessment to a single scale. Despite the limited number of female participants in our, the female-to-male ratio (approximately 1:5) reflects the gender distribution commonly reported in clinical ASD samples.2 Although we focused on symptom severity to examine gender-related differences, the smaller number of girls in each severity range limited the statistical power of our analyses. This remains an important limitation, and future studies with larger and more balanced samples are needed to confirm and build upon these findings. Nevertheless, the study’s focus on early clinical presentation and its attempt to explore symptom variability among early ages contribute valuable insights to the literature and may inform future gender-sensitive assessment strategies. In light of these limitations, future studies with larger and more balanced samples, ideally drawn from population-based cohorts, are needed to more effectively address the research question

In summary, our findings suggest that girls may be referred for clinical evaluation only when their symptoms are more pronounced. In the group with minimal to no symptoms, girls had significantly higher total scores and elevated ratings in domains such as nonverbal communication, imitation, and social interaction. These results point to a potential referral bias and underscore the risk that milder difficulties in girls may go unnoticed. Although the sample size was limited, particularly for females, this study highlights the importance of early, gender-sensitive approaches and calls for further research using larger and more balanced samples.

Given the critical importance of early diagnosis, it is essential that girls are not overlooked, ensuring they gain timely access to interventions, which is of significant importance for society as a whole.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Hacettepe University (2023/04-18).

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and statistical manual. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: APA; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Shaw KA, Maenner MJ, Baio J, et al. Early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 years - early autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, six sites, united states, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ 2020; 69: 1-11. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6903a1

- Werling DM, Geschwind DH. Understanding sex bias in autism spectrum disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110: 4868-4869. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1301602110

- Hull L, Petrides K, Mandy W. The female autism phenotype and camouflaging: a narrative review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2020; 7: 306-317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00197-9

- Happé FG, Mansour H, Barrett P, et al. Demographic and cognitive profile of individuals seeking a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in adulthood. J Autism Dev Disord 2016; 46: 3469-3480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2886-2

- Dalsgaard S, Thorsteinsson E, Trabjerg BB, et al. Incidence rates and cumulative incidences of the full spectrum of diagnosed mental disorders in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2020; 77: 155-164. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3523

- Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes PJ, et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet 2020; 396: 565-582. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0

- Natoli K, Brown A, Bent CA, Luu J, Hudry K. No sex differences in core autism features, social functioning, cognition or co-occurring conditions in young autistic children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 2023; 107: 102207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2023.102207

- Fulton AM, Paynter JM, Trembath D. Gender comparisons in children with ASD entering early intervention. Res Dev Disabil 2017; 68: 27-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.07.009

- Stephenson KG, Norris M, Butter EM. Sex-based differences in autism symptoms in a large, clinically-referred sample of preschool-aged children with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord 2023; 53: 624-632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04836-2

- İncekaş Gassaloğlu S, Baykara B, Avcil S, Demiral Y. Validity and reliability analysis of Turkish version of childhood autism rating scale. Turk Psikiyatri Derg 2016; 27: 266-274.

- Blanco MB, Dausmann KH, Faherty SL, et al. Hibernation in a primate: does sleep occur? R Soc Open Sci 2016; 3: 160282. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160282

- McFayden TC, Putnam O, Grzadzinski R, Harrop C. Sex differences in the developmental trajectories of autism spectrum disorder. Curr Dev Disord Rep 2023; 10: 80-91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-023-00270-y

- Zwaigenbaum L, Bryson SE, Szatmari P, et al. Sex differences in children with autism spectrum disorder identified within a high-risk infant cohort. J Autism Dev Disord 2012; 42: 2585-2596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1515-y

- Reinhardt VP, Wetherby AM, Schatschneider C, Lord C. Examination of sex differences in a large sample of young children with autism spectrum disorder and typical development. J Autism Dev Disord 2015; 45: 697-706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2223-6

- Xiong H, Liu X, Yang F, et al. Developmental language differences in children with autism spectrum disorders and possible sex difference. J Autism Dev Disord 2024; 54: 841-851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05806-6

- Van Wijngaarden-Cremers PJ, van Eeten E, Groen WB, et al. Gender and age differences in the core triad of impairments in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord 2014; 44: 627-635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1913-9

- Knutsen J, Crossman M, Perrin J, Shui A, Kuhlthau K. Sex differences in restricted repetitive behaviors and interests in children with autism spectrum disorder: an autism treatment network study. Autism 2019; 23: 858-868. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318786490

- Harrop C, Green J, Hudry K; PACT Consortium. Play complexity and toy engagement in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder: do girls and boys differ? Autism 2017; 21: 37-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315622410

- Akçakın M. Sex differences in autism [Otizmde cinsiyet farklılıkları]. Turk J Child Adolesc Ment Health 2002; 9: 3-15.

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.