Graphical Abstract

Abstract

Background. Inherited renal hypomagnesemia is rare but may indicate an underlying genetic condition, and it should be considered when evaluating unexplained hypomagnesemia. 17q12 deletion syndrome, a recurrent microdeletion including HNF1B (hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 beta) and neighboring genes such as LHX1 (LIM homeobox 1) and ACACA (acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha), is associated with renal magnesium wasting, neurodevelopmental deficits, and multi-organ involvement. However, spinal cord anomalies, particularly syringomyelia, have not been reported to date.

Case Presentation. A 12-year-old girl was referred to our pediatric nephrology department with frequent urination. Her medical history included neurodevelopmental delay, scoliosis, and behavioral abnormalities. Laboratory tests showed a serum magnesium level of 1.5 mg/dL and an elevated fractional urine magnesium excretion of 4.1%. Serum glucose, aspartate transaminase, and alanine transaminase were mildly elevated. There were no structural anomalies on urinary ultrasound and cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Radiological investigations revealed thoracolumbar scoliosis on spinal X-ray and a central syrinx extending from T3 to T6 levels on thoracic spinal MRI. Chromosomal microarray analysis identified a 1.4 Mb deletion at chromosome 17q12, which contains the HNF1B gene, confirming the diagnosis of 17q12 deletion syndrome. Oral magnesium supplementation was initiated, and the patient was referred to a multidisciplinary care team.

Conclusions. This case highlights the importance of considering genetic etiologies, particularly 17q12 deletion syndrome, in children presenting with persistent hypomagnesemia and neurodevelopmental delay. Recognizing electrolyte imbalances, despite the absence of renal structural abnormalities, and identifying coexisting spinal cord anomalies, such as syringomyelia, may guide timely genetic evaluation and enable earlier diagnosis.

Keywords: 17q12 deletion, case report, HNF1B, hypomagnesemia, syringomyelia

Introduction

Hypomagnesemia is commonly observed in hospitalized patients, typically due to inadequate dietary intake or excessive gastrointestinal or renal losses. Although inherited forms of renal hypomagnesemia are rare, they are clinically significant and should be considered in cases of persistent and unexplained hypomagnesemia.1 One such genetic cause is 17q12 deletion syndrome, involving haploinsufficiency of the HNF1B (hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 beta) gene.2

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain HNF1B-related renal magnesium wasting. HNF1B is known to regulate the expression of key distal convoluted tubule transporters and channels involved in magnesium reabsorption, including TRPM6 (transient receptor potential melastatin 6), FXYD2 (FXYD domain-containing ion transport regulator 2), and KCNJ16 (potassium inwardly rectifying channel subfamily J member 16). Reduced transcriptional activity of these genes due to HNF1B haploinsufficiency impairs active magnesium transport, leading to renal magnesium loss and hypomagnesemia.2

Beyond HNF1B, the recurrent 17q12 microdeletion typically includes 15–20 protein-coding genes, such as LHX1 (LIM homeobox 1), ACACA (acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha), and ZNHIT3 (zinc finger HIT-type containing 3). The combined loss of these neighboring genes may contribute to the neurodevelopmental and other extrarenal features of the syndrome.2-4

The clinical phenotype of 17q12 deletion syndrome is markedly heterogeneous. It may involve structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney and urinary tract (including hydronephrosis, polycystic kidney disease, or hypoplastic/dysplastic kidneys), metabolic disturbances such as hyperuricemia and maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 5 (MODY5), genital anomalies, hepatic disorders (e.g., liver cysts, hypertransaminasemia), and various neurodevelopmental or neuropsychiatric disorders, including developmental delay, intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and other psychiatric conditions.2,3

While renal, hepatic, and neurodevelopmental abnormalities are well-established in 17q12 deletion syndrome, spinal cord anomalies, particularly syringomyelia, have not been reported to date. Here, we describe a pediatric patient with hypomagnesemia and neurodevelopmental delay, who was ultimately diagnosed with 17q12 deletion syndrome, presenting with coexisting thoracolumbar scoliosis and spinal syringomyelia.

Case Presentation

A 12-year-old girl was referred to our pediatric nephrology department in December 2023 due to frequent urination. She had no polyuria, polydipsia, urinary tract infections, urine incontinence, or constipation. Her medical history included intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder, with ongoing care and treatment from pediatric psychiatry and neurology, in which she was prescribed sertraline and risperidone.

She was born at term by cesarean section, with a birth weight of 2300 g, and did not require neonatal critical care. There was no parental consanguinity, and the family history was unremarkable. She started walking at 12 months and spoke her first words at 18 months; however, by the age of 4 years, she was unable to build meaningful sentences.

On physical examination, she exhibited developmental delay with cognitive and social deficits compared to her age-matched peers. No apparent dysmorphic features were noted other than prominent auricles. Her weight was 34 kg (SD score: -1.56) and height was 150 cm (SD score: -0.48), corresponding to a body mass index (BMI) of 15.1 kg/m2 (SD score: -1.75). Blood pressure was 105/62 mmHg (systolic 53rd percentile, diastolic 51st percentile). Thoracolumbar scoliosis was observed. Neurological, cardiovascular, and abdominal examinations were otherwise unremarkable.

Laboratory findings revealed a serum glucose level of 141 mg/dL (postprandial), creatinine 0.55 mg/dL, sodium 137 mmol/L, potassium 3.7 mmol/L, chloride 100 mmol/L, calcium 9.1 mg/dL, phosphorus 3.8 mg/dL, and magnesium 1.5 mg/dL (reference range, 1.6–2.1 mg/dL). Blood gas analysis demonstrated a pH of 7.46 and a bicarbonate level of 26.2 mmol/L. Complete blood count was within normal limits except for a mildly decreased platelet count (131×10³/µL). Liver enzymes were mildly elevated with aspartate transaminase (AST) 28 IU/L and alanine transaminase (ALT) 37 IU/L. Urinalysis showed a pH of 5.5, specific gravity of 1.006, and no evidence of hematuria, proteinuria, or sediment abnormalities. Spot urine analysis revealed an elevated fractional excretion of magnesium (FeMg) of 4.1% and a normal calcium-to-creatinine ratio of 0.23 mg/mg.

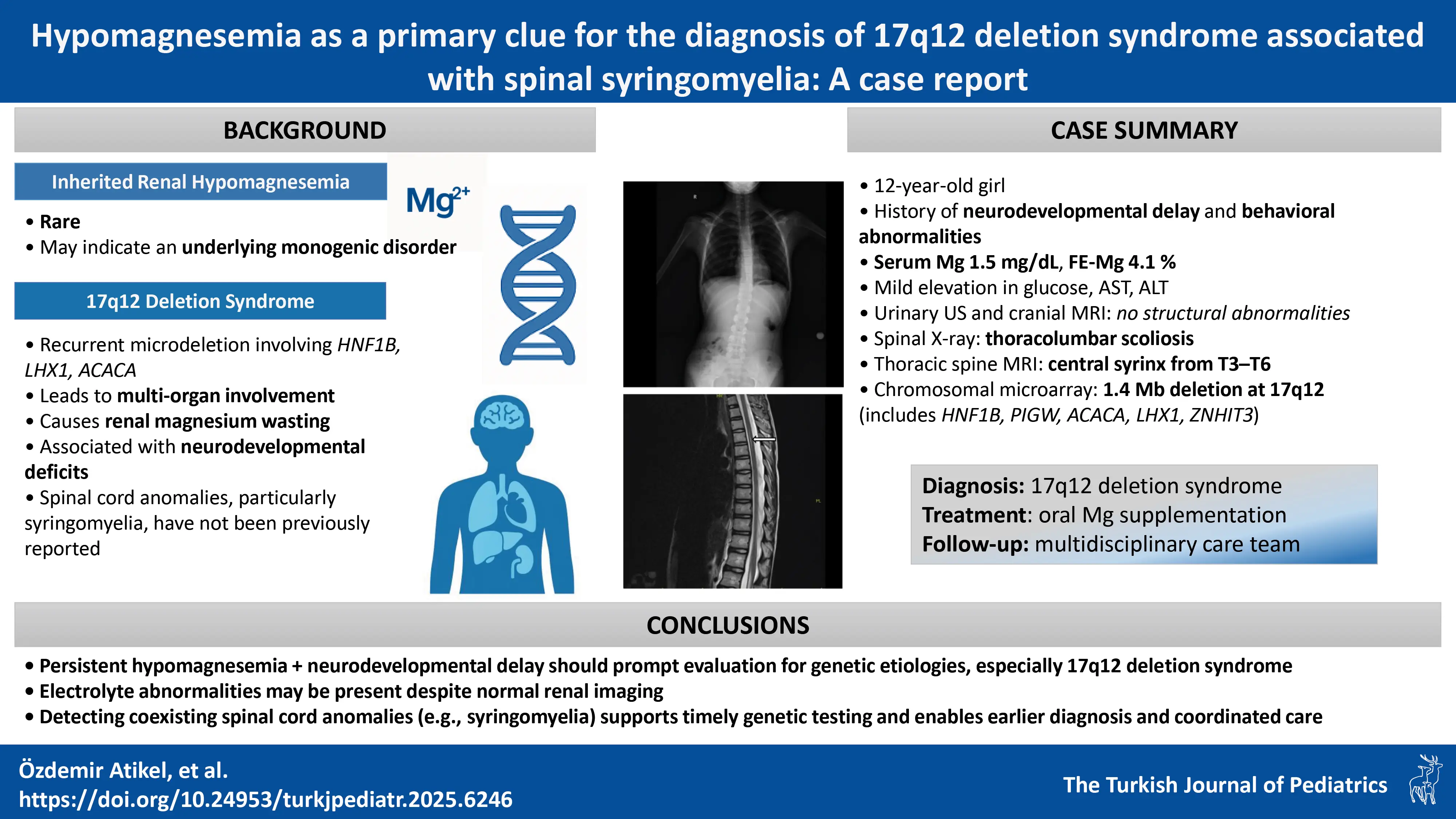

The patient, who had been previously followed by pediatric neurology, was noted to have borderline serum magnesium levels (1.7 mg/dL) approximately one year earlier, along with mildly elevated AST (51 IU/L) and ALT (45 IU/L) levels. Thyroid function tests; vitamin B12, folic acid, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels; carnitine-acylcarnitine analysis by tandem mass spectrometry; urinary organic acid analysis; and serum lactate, pyruvate, and ammonia levels were all within normal limits. Urinary, hepatobiliary, and suprapubic pelvic ultrasonography findings were normal. Scoliosis radiography confirmed thoracolumbar scoliosis (Fig. 1a). Brain MRI showed no abnormalities. Cervical MRI revealed loss of cervical lordosis, while thoracic MRI demonstrated a central syrinx in the spinal cord extending from the T3 to T6 levels (Fig. 1b).

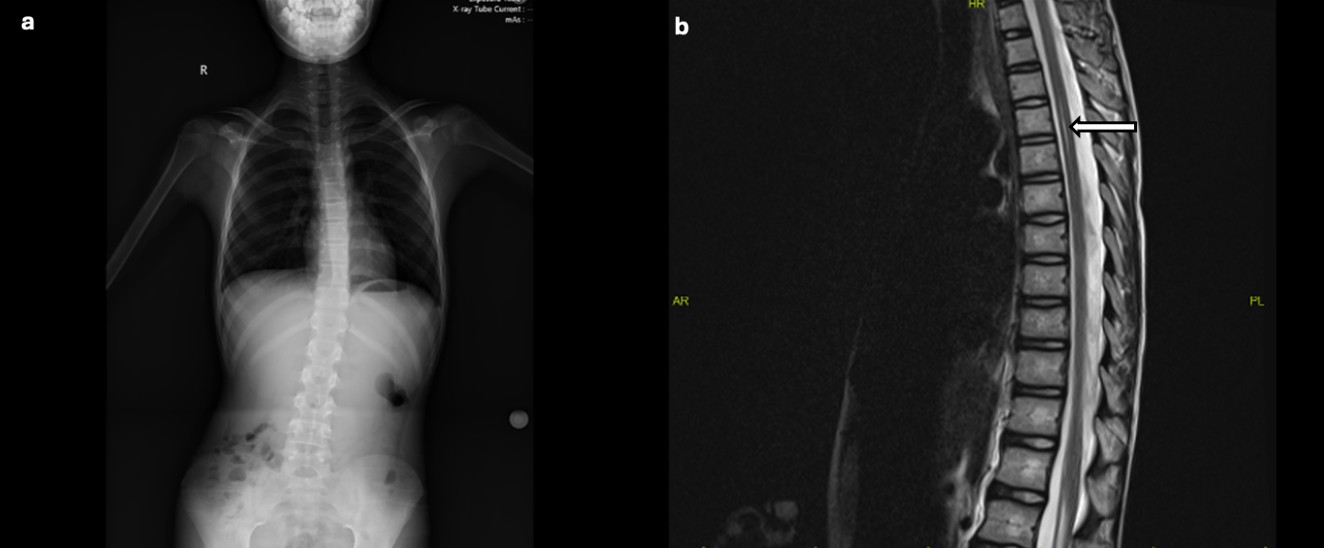

She was started on oral magnesium supplementation and referred to the medical genetics department for further evaluation. Chromosomal microarray analysis was performed on genomic DNA extracted from peripheral blood samples using the Qiagen DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Variant annotation was based on the GRCh38 (hg38) human genome reference, and interpretation followed the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) standards. The analysis identified a heterozygous 1.4-Mb deletion at 17q12 (arr[GRCh38] 17q12(36459737_37889808)x1), encompassing several genes including HNF1B, PIGW (phosphatidylinositol-glycan biosynthesis class W protein), ACACA, LHX1 and ZNHIT3. The microarray profile is shown in Fig. 2a, and the schematic representation of all genes within this region is displayed in Fig. 2b.

Following the confirmation of 17q12 deletion syndrome, pediatric endocrinology and gastroenterology consultations were added to her ongoing multidisciplinary follow-up under pediatric neurology, psychiatry, and nephrology. At the most recent follow-up visit in April 2025, her weight was 40 kg (SD score: -2.44), height was 154 cm (SD score: -1.18), and BMI was 16.8 kg/m2 (SD score: -1.95). Blood pressure was 110/65 mmHg. Laboratory tests demonstrated a serum glucose of 104 mg/dL (fasting), insulin level of 6 µIU/mL, and a HOMA-IR index of 1.54. Serum creatinine was 0.61 mg/dL, uric acid 5.6 mg/dL, and magnesium 1.9 mg/dL. Other electrolytes, as well as blood pH and bicarbonate levels, were within normal limits. Liver function tests showed mildly increased levels of AST (47 IU/L), ALT (59 IU/L), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT: 104 IU/L). The lipid profile, including total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), and triglycerides, was normal (151/70/71/48 mg/dL, respectively). Urinalysis showed a pH of 5.5, a specific gravity of 1.022, no proteinuria, no glucosuria, and 5 erythrocytes per high-power field. A summary of the initial and follow-up laboratory findings is presented in Table I.

| ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase. | ||

| Table I. Summary of initial and follow-up laboratory findings. | ||

| Parameter |

|

|

| Serum magnesium (mg/dL) |

|

|

| Fractional excretion of magnesium (%) |

|

|

| Serum potassium (mmol/L) |

|

|

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) |

|

|

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dL) |

|

|

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) |

|

|

| Serum glucose (mg/dL) |

|

|

| AST / ALT (IU/L) |

|

|

| GGT (IU/L) |

|

|

| Serum sodium (mmol/L) |

|

|

| Serum chloride (mmol/L) |

|

|

| Blood pH |

|

|

| Serum bicarbonate (mmol/L) |

|

|

| Serum uric acid (mg/dL) |

|

|

| Urine calcium / creatinine ratio (mg/mg) |

|

|

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardians for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Discussion

The 17q12 deletion syndrome is a recurrent multigenic microdeletion encompassing approximately 15 protein-coding genes including HNF1B, PIGW, ACACA, LHX1 and ZNHIT3.3,4 This chromosomal abnormality results in a heterogeneous phenotype involving renal, urogenital, metabolic, neurodevelopmental and psychiatric abnormalities. In our patient, the two main clinical findings, persistent hypomagnesemia and neurodevelopmental delay, reflect this dual renal and neurological involvement.3

In 17q12 deletion syndrome, prenatal imaging may reveal renal anomalies such as increased echogenicity and poor corticomedullary differentiation, whereas postnatal findings may identify renal hypoplasia, dysplasia, multicystic dysplastic kidney, or renal agenesis.3 Other urinary tract anomalies reported in this syndrome include horseshoe kidney, ureteropelvic junction obstruction, isolated hydronephrosis, and hydroureter. Tubulointerstitial disease may manifest with impaired urine-concentrating capacity, unremarkable urinary sediment, minimal proteinuria, hyperuricemia, hypomagnesemia and hypokalemia.3 In our patient, renal ultrasonography revealed no structural abnormalities; however, persistent hypomagnesemia and elevated urinary magnesium excretion suggested functional tubular impairment. This finding is consistent with previous observations in HNF1B-related disease, where renal magnesium wasting has been reported in up to 62% of patients despite normal renal imaging.5

Even in the absence of renal malformations, 17q12 deletion syndrome should be considered as a possible etiology in children presenting with neurodevelopmental disorders and electrolyte disturbances. Hypomagnesemia, in particular, served as the biochemical marker that prompted genetic investigation in our patient. We initially suspected Gitelman syndrome based on the presence of hypomagnesemia and mild metabolic alkalosis; however, the lack of hypocalciuria and only borderline hypokalemia pointed to an alternative diagnosis. HNF1B haploinsufficiency is known to impair distal tubular magnesium reabsorption, leading to renal magnesium wasting, mild hypokalemia, and metabolic alkalosis, often resembling a Gitelman-like tubulopathy.6 Although classical findings such as severe hypokalemia or obvious metabolic alkalosis were not prominent in our patient, persistent hypomagnesemia and elevated fractional renal magnesium excretion were suggestive of distal tubular dysfunction, ultimately leading to the diagnosis of 17q12 deletion syndrome. Psychotropic medications such as sertraline and risperidone have been reported to influence magnesium homeostasis, but current evidence suggests they do not cause clinically relevant magnesium depletion. Experimental and clinical data indicate that these agents may even increase intracellular magnesium concentrations and support neurochemical stability through modulation of glutamate and GABAergic pathways.7,8 In our patient, the persistence of hypomagnesemia with elevated FeMg, despite ongoing psychotropic therapy and in the absence of other implicated drugs, supports a renal magnesium-wasting mechanism secondary to HNF1B haploinsufficiency rather than a medication effect. Although higher fractional excretion of magnesium (FeMg) values have been reported in severe renal magnesium-wasting states, milder elevations, such as the 4.1% observed in our patient, can still indicate renal loss, particularly in early or partial distal convoluted tubule dysfunction. The persistently low serum magnesium and absence of extrarenal losses further support a renal etiology. Nutritional status was also reviewed to exclude dietary magnesium deficiency; the patient had no signs of malnutrition or poor intake, making inadequate magnesium intake an unlikely cause.

Neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric manifestations are also common in 17q12 deletion syndrome and include developmental delay, intellectual disability, ASD, ADHD, and, less frequently, anxiety, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.3 Our patient exhibited moderate neurodevelopmental delay and ASD features beginning in early childhood, requiring ongoing evaluation by pediatric psychiatry and neurology. Although brain MRI findings were normal, her clinical features are consistent with previous reports indicating that functional or ultrastructural brain alterations, rather than major anatomic defects, may underlie the neurological manifestations of 17q12 deletion syndrome.9 Milone et al.9 described nonspecific brain abnormalities in affected patients, including ventricular dilatation, white-matter signal changes, hippocampal atrophy, and corpus callosum agenesis or thinning. These reports support that normal neuroimaging does not exclude neurocognitive dysfunction in 17q12 deletion syndrome. The loss of other genes within the 17q12 interval, particularly LHX1 and ACACA, may underlie the neurodevelopmental and extrarenal manifestations through disruption of neuronal differentiation and metabolic pathways.⁴ LHX1 encodes a LIM-homeodomain transcription factor essential for neuronal differentiation and early embryonic patterning, whereas ACACA participates in fatty-acid metabolism and neuronal energy homeostasis.4 Haploinsufficiency of these genes likely contributes to the neurodevelopmental phenotype observed in our patient, supporting a multigenic rather than a single-gene pathogenesis.

Neuroimaging findings in our patient included loss of cervical lordosis and a thoracic spinal cord syrinx extending from T3 to T6. Although such findings have not been routinely reported in association with 17q12 deletion syndrome, they may represent underrecognized aspects of its broader neurodevelopmental phenotype. Existing literature has focused mainly on brain malformations. The coexistence of spinal syringomyelia in our patient therefore may reflect an underrecognized manifestation of the broader neurodevelopmental phenotype associated with 17q12 deletion syndrome. Several mechanisms may be proposed: (1) loss of neurodevelopmentally relevant genes within the deleted 17q12 interval, such as LHX1, which plays a role in neuronal patterning and differentiation; (2) altered cerebrospinal fluid dynamics due to subtle maldevelopment of the spinal canal or hindbrain structures, even in the absence of Chiari malformation; or (3) an incidental finding unrelated to the microdeletion. Given the single-case nature of this report, causality cannot be established, and further studies are required to clarify this potential association. Our case and these hypotheses highlight the potential importance of performing spinal imaging in selected patients with 17q12 deletions, especially in those with neuromotor or postural anomalies such as scoliosis.

Beyond the renal phenotype, HNF1B acts as a key transcriptional regulator during organogenesis of the pancreas, liver, and genitourinary tract.2,3 Its haploinsufficiency may disrupt pancreatic β-cell differentiation and hepatobiliary development, leading to mild hyperglycemia, elevated liver enzyme levels, and, in some cases, reproductive tract anomalies. These mechanisms account for the broad systemic manifestations observed in 17q12 deletion syndrome.2,3 Mildly elevated glucose and liver enzyme levels in our patient necessitated consultation with endocrinology and gastroenterology teams, and inclusion in a structured multidisciplinary monitoring program to anticipate future endocrine and metabolic complications, including the development of MODY5.

In conclusion, this case highlights the importance of considering 17q12 deletion syndrome in children presenting with hypomagnesemia and neurodevelopmental delay, even in the absence of structural renal or cerebral anomalies. The coexistence of thoracolumbar scoliosis and spinal syringomyelia in our patient further emphasizes the phenotypic diversity of this syndrome. Early recognition of 17q12 deletion syndrome enables effective management, genetic counseling, and coordinated multidisciplinary follow-up. Serum magnesium measurement should be included in the diagnostic assessment of children with developmental delays, cognitive impairment, or autism spectrum disorder, especially when accompanied by subtle electrolyte abnormalities. Clinicians should remain alert for persistent hypomagnesemia as a potential early clue to underlying syndromic conditions such as 17q12 deletion syndrome.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardians for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Knoers NV. Inherited forms of renal hypomagnesemia: an update. Pediatr Nephrol 2009; 24: 697-705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-008-0968-x

- Sánchez-Cazorla E, Carrera N, García-González MÁ. HNF1B transcription factor: key regulator in renal physiology and pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2024; 25: 10609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms251910609

- Mitchel MW, Moreno-De-Luca D, Myers SM, et al. 17q12 Recurrent Deletion Syndrome. 2016 Dec 8 [Updated 2025 Aug 14]. In: Adam MP, Bick S, Mirzaa GM, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK401562/

- Clissold RL, Hamilton AJ, Hattersley AT, Ellard S, Bingham C. HNF1B-associated renal and extra-renal disease-an expanding clinical spectrum. Nat Rev Nephrol 2015; 11: 102-112. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2014.232

- Faguer S, Decramer S, Chassaing N, et al. Diagnosis, management, and prognosis of HNF1B nephropathy in adulthood. Kidney Int 2011; 80: 768-776. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2011.225

- Adalat S, Hayes WN, Bryant WA, et al. HNF1B mutations are associated with a Gitelman-like tubulopathy that develops during childhood. Kidney Int Rep 2019; 4: 1304-1311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2019.05.019

- Nechifor M. Interactions between magnesium and psychotropic drugs. Magnes Res 2008; 21: 97-100.

- Nechifor M. Magnesium in psychoses (schizophrenia and bipolar disorders). In: Vink R, Nechifor M, editors. Magnesium in the Central Nervous System. Adelaide (AU): University of Adelaide Press; 2011. https://doi.org/10.1017/UPO9780987073051.023

- Milone R, Tancredi R, Cosenza A, et al. 17q12 recurrent deletions and duplications: description of a case series with neuropsychiatric phenotype. Genes (Basel) 2021; 12: 1660. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12111660

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.