Graphical Abstract

Abstract

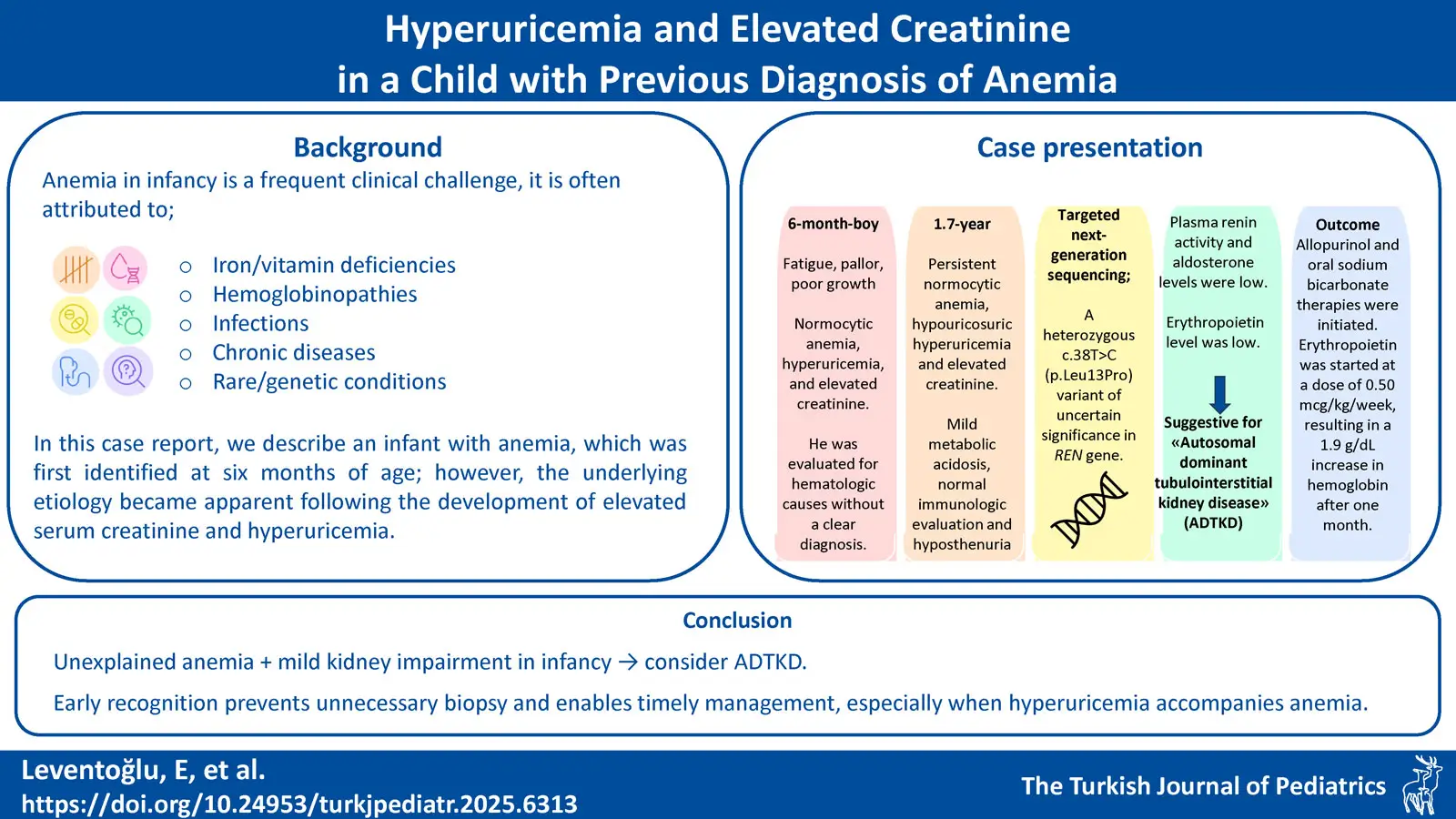

Background. Anemia in infancy is a frequent clinical challenge, often attributed to nutritional deficiencies. However, persistent or unexplained anemia warrants further investigation. In this case report, we describe an infant in whom anemia was first identified at six months of age; however, the underlying etiology became apparent only after the development of elevated serum creatinine and hyperuricemia.

Case Presentation. We present a 1.7-year-old boy with persistent normocytic anemia, hyperuricemia, and elevated creatinine, initially evaluated for hematologic causes without a clear diagnosis. Despite normal growth, laboratory findings revealed hypouricosuria, hyposthenuria, and mildly decreased kidney function. Imaging and immunologic work-up were unremarkable. Due to multisystem involvement, genetic testing was performed and identified a heterozygous variant in REN gene, suggesting a potential link to autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease (ADTKD). Due to persistent anemia refractory to iron therapy, erythropoietin was initiated at a dose of 0.50 µg/kg/week, resulting in a 1.9 g/dL increase in hemoglobin after one month. The family was appropriately informed about the chronic nature of the kidney disease, and a lifelong follow-up strategy was established.

Conclusion. This case underscores the importance of considering ADTKD in pediatric patients presenting with unexplained anemia and mild kidney impairment, even in the absence of a family history. Early diagnosis can prevent unnecessary procedures such as kidney biopsy, allow the timely initiation of supportive treatments, and improve long-term outcomes. Pediatricians, pediatric hematologists and pediatric nephrologists should be aware of this diagnostic possibility, particularly when anemia is accompanied by hyperuricemia and elevated creatinine in infancy.

Keywords: anemia, glomerular filtration rate, REN gene, renin-angiotensin system

Introduction

Anemia is a condition characterized by a deficiency of healthy red blood cells (RBCs) in the body and is among the most common hematological conditions in children, affecting more than 269 million children worldwide.1 According to the World Health Organization, the prevalence of anemia in children under five years of age was approximately 40% in 2019.2 The most common etiological cause in this age group is iron deficiency due to inadequate intake, which accounts for 25–50% of cases.3 In addition, hemoglobinopathies, particularly sickle cell disease and thalassemia, constitute clinically significant causes, with a reported prevalence ranging from 6% to 9%.4 Moreover, deficiencies of vitamins such as vitamin B12 and folate, infectious diseases including malaria and schistosomiasis, chronic blood loss, inflammatory conditions or chronic kidney diseases (CKD) represent important etiological factors for anemia in childhood.4 During infancy, clinical signs suggestive of CKD include feeding difficulties, failure to thrive, developmental delay, polyuria, polydipsia, recurrent vomiting or episodes of dehydration, electrolyte disturbances and hypertension. Regarding anemia, it usually appears in children with CKD stage 3 and becomes more common and clinically significant in advanced stages.5,6 Whatever the cause, it can lead to a reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of cells, causing clinical symptoms of anemia in infants such as fatigue, pallor, poor growth and failure to thrive.7

In rare types of anemia that do not fit previously described etiological categories, a group of patients remain undiagnosed despite comprehensive diagnostic evaluations. However, advances in targeted next-generation sequencing have facilitated the identification of the underlying genetic cause in more than 60% of such cases.8 In this case report, we describe an infant in whom anemia was first identified at six months of age; however, the underlying etiology was identified through genetic analysis only after the development of elevated serum creatinine and hyperuricemia.

Case Presentation

A 1.7-year-old boy with anemia was referred to the department of pediatric nephrology for hyperuricemia and elevated creatinine. He was born full term from an uneventful pregnancy from unrelated parents. There was no family history of hematological or nephrological diseases. His birth weight was 3.4 kg at 39 weeks of gestation. There was no history of jaundice in the neonatal period. He was breastfed for the first 6 months of his life, received oral iron prophylaxis. There was no infection or symptoms of fever, rash, dysuria, hematuria, vomiting or bloody stools in his medical history, however, normocytic anemia was noticed when he presented with fatigue, pallor and poor growth at the age of 6 months.

At the age of 6 months, white blood cell (WBC) count was 9870/μL, hemoglobin (Hb) 7.1 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 90.2 fL, thrombocyte count 378000 /μL, and reticulocyte ratio 1.2%. In the peripheral smear, erythrocytes had normochromic normocytic appearance. There were no blasts; platelets were abundant and clustered. Serum iron level was slightly low (28 μg/dL), but total iron binding capacity, ferritin, folate and vitamin B12 levels were normal. Direct Coombs test was negative and haptoglobin was normal. Fecal occult blood was negative. In serum biochemistry, there was no elevated lactate dehydrogenase or hyperbilirubinemia, however, serum creatinine (0.71 mg/dL; normal range: 0.15-0.34 mg/dL)9 and uric acid levels (6.9 mg/dL normal range: 2.7-4.5 mg/dL)10were high. Hemoglobin high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), osmotic fragility test, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, pyruvate kinase, and 5’ nucleotidase levels were normal. Bone marrow aspiration was normocellular, normoblastic erythropoiesis was present, and no dysplasia was observed in normoblasts. The etiology of anemia could not be elucidated, and the patient was followed up with 2 mg/kg elemental iron daily.

At the time of referral to pediatric nephrology, physical examination showed normal growth with a body weight of 10 kg (10-25th percentiles) and a height of 79 cm (10-25th percentiles). His blood pressure was 80/50 mmHg (<90th percentile). Skin thickness and turgor were normal but markedly pale. Liver or spleen was not palpable. He had anemia (Hb 7.7 g/dL, MCV 85.5 fL, RBC 2.75 x106/µL, RDW 13.3%), but WBC and platelet count were normal. Kidney function tests showed elevated serum creatinine and reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (0.83 mg/dL and 39 mL/min/1.73m2, respectively). He had hyperuricemia (8.8 mg/dL). Serum electrolyte and albumin levels were normal. Blood gas analysis showed pH 7.33 and HCO3 19.2 mmol/L with negative base excess and normal anion gap. Urinalysis showed a pH of 6.5, specific gravity of 1002, and did not show hematuria/proteinuria or glycosuria. Spot urine uric acid was 5.5 mg/dL (normal range 37-97 mg/dL) and fractional excretion of uric acid was as low as 4.59%.11 Urine output was 4.4 mL/kg/hr. In the immunologic evaluation, serum complement levels were normal. Antinuclear antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and anti-double-stranded DNA were all negative (Table I). Ultrasonography showed normal-sized kidneys with normal parenchymal echogenicity. Renal Doppler ultrasound was normal. The genetic examination was performed due to persistent anemia, elevated creatinine, hypouricosuric hyperuricemia and hyposthenuria. Targeted next-generation sequencing revealed a heterozygous c.38T>C (p.Leu13Pro) variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in REN gene. The REN gene encodes the renin protein, and the variant was inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Segregation analysis revealed that the variant was not present in either parent, indicating that the identified REN variant arose de novo. In analyses evaluating the clinical concordance of the identified variant, the patient’s plasma renin activity was 1.1 ng/mL/h (normal range 2.9 to 24 ng/mL/h) with a low serum aldosterone level. Also, erythropoietin level was 2.9 mU/mL (normal range: 4-21 mU/mL). Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease (ADTKD).12

| ANA: anti-nuclear antibody, ANCA: anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody, Anti-dsDNA: anti-double stranded deoxyribonucleic acid, C3: Complement 3, C4: Complement 4, DBP: Diastolic blood pressure, eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate, FeUA: Fractional excretion of uric acid, MCV: Mean corpuscular volume, N/A: not available, RBC: Red blood cell, RDW: Red cell distribution width, SBP: Systolic blood pressure. | |||

| Table I. Clinical characteristics and laboratory results of the patient | |||

|

|

|

|

|

| Age (year) |

|

|

|

| Anthropometric measurements | |||

| Height, cm (percentile) |

|

|

|

| Weight, kg (percentile) |

|

|

|

| Blood pressure | |||

| SBP, mmHg (percentile) |

|

|

|

| DBP, mmHg (percentile) |

|

|

|

| Blood | |||

| Hemoglobulin (g/dL) |

|

|

|

| MCV (fL) |

|

|

|

| RBC (106/µL) |

|

|

|

| RDW (%) |

|

|

|

| White blood cell (/µL) |

|

|

|

| Platelets (/µL) |

|

|

|

| Creatinine (mg/dL) |

|

|

|

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) |

|

|

|

| Uric acid (mg/dL) |

|

|

|

| Albumin (g/dL) |

|

|

|

| Calcium (mg/dL) |

|

|

|

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) |

|

|

|

| Magnesium (mg/dL) |

|

|

|

| Sodium (mmol/L) |

|

|

|

| Chloride (mmol/L) |

|

|

|

| Potassium (mmol/L) |

|

|

|

| pH |

|

|

|

| HCO3 (mmol/L) |

|

|

|

| Base excess (mmol/L) |

|

|

|

| Anion gap (mEq/L) |

|

|

|

| C3 (mg/dL) |

|

|

|

| C4 (mg/dL) |

|

|

|

| ANA |

|

|

|

| ANCA |

|

|

|

| Anti-ds DNA |

|

|

|

| Plasma renin activity (ng/mL/h) |

|

|

|

| Aldosterone (ng/dL) |

|

|

|

| Erythropoietin (mU/mL) |

|

|

|

| Urine | |||

| pH |

|

|

|

| Density |

|

|

|

| Protein/creatinine (mg/mg) |

|

|

|

| Leucocyte (/HPF) |

|

|

|

| Erythrocyte (/HPF) |

|

|

|

| Uric acid (mg/dL) |

|

|

|

| FeUA (%) |

|

|

|

As the patient had not yet developed significant hypotension or hyperkalemia, a high-sodium diet or fludrocortisone therapy was not initiated at this stage. However, allopurinol and oral sodium bicarbonate therapies were initiated. Due to persistent anemia refractory to iron therapy, erythropoietin was initiated at a dose of 0.50 µg/kg/week, resulting in a 1.9 g/dL increase in hemoglobin after one month. The patient’s clinical features and laboratory values at the time of initial referral to pediatric nephrology and at the end of the 9-month follow-up period are shown in Table I.

Written informed consent was obtained from parents for the use of clinical and laboratory data for this publication.

Discussion

Autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease is characterized by a bland urinary sediment and a gradual progression of CKD and eventually necessitates kidney replacement therapy. The most common causes of ADTKD include mutations in UMOD, MUC1, and REN genes.12 In a study by Živná M et al., pathogenic variants were identified in the UMOD gene in 38% of cases, in the MUC1 gene in 21%, and in the REN gene in only 3% of cases.13 Pathogenic mutations in the REN gene lead to a reduction in the production and secretion of both wild-type prorenin and renin. Therefore, all affected patients exhibit low plasma renin and aldosterone levels.14

Fatigue, refusal to feed, and failure to thrive can be seen even in the infantile period in ADTKD caused by REN mutation. Early onset anemia, increased serum creatinine, decreased eGFR, hyperuricemia, mild hyperkalemia and acidosis are usually present.15 Most patients develop kidney failure after the age of 35.14 However, due to the rarity of the disease, the age of diagnosis may be delayed up to 57 years despite symptoms and signs at an early age.16 Consistent with previously reported cases of ADTKD, our patient also exhibited hallmark features including anemia, hyperuricemia, and elevated serum creatinine. Although the diagnosis might appear somewhat delayed by a few months, it was established at the remarkably early age of 1.7 years, highlighting the potential for early detection when clinical and laboratory findings are carefully integrated and evaluated in the context of ADTKD. A non-specific kidney biopsy may also be performed in the diagnosis of ADTKD.17 However, we believe that genetic analysis should be prioritized before considering interventional procedures such as kidney biopsy, particularly when there is a family history of CKD consistent with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. In our patient, the symptoms and findings were highly consistent with ADTKD, however there was no history of kidney disease in his family. This case highlights that when clinical and laboratory findings are highly consistent with our preliminary diagnosis, genetic testing should be performed appropriately, even in the absence of a family history.

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system plays a critical role in the diagnosis and pathophysiology of CKD. It regulates glomerular filtration pressure and fluid-electrolyte balance in the kidneys. Renin secreted by juxtaglomerular cells converts angiotensinogen to angiotensin I. Angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor that is subsequently formed, stimulates aldosterone secretion. As a result, glomerular pressure increases, and sodium retention and potassium excretion occur in the distal tubules. However, renin levels do not always increase in CKD; they may increase in the early stages, decrease in the advanced stages, or be characteristically low in genetic disorders. Therefore, measuring renin-angiotensin-aldosterone activity or monitoring its effects is important in CKD for both diagnosis and prognosis.18 In REN mutation, the decrease in eGFR may be due to insufficient renin production during embryonic development and less kidney mass than it should be. Decreased renin levels disrupt local renin-angiotensin-aldosterone activity and glomerular hemodynamic regulation. Insufficient angiotensin II cannot balance afferent and efferent arteriolar tone, leading to decreased filtration pressure, hypoperfusion, and eventual ischemia. Therefore, scar tissue forms, eGFR declines, and CKD progresses. The REN mutation also impairs sodium reabsorption in the distal tubule and collecting ducts, inhibiting potassium and hydrogen ion excretion, leading to hyperkalemia and non-anion gap metabolic acidosis in the long term. The stress and inflammation that develop due to intracellular ion imbalance increase interstitial fibrosis and structural damage. In addition, uric acid excretion from the kidney decreases, and serum uric acid levels rise. This accelerates oxidative stress and fibrosis, deepens tubulointerstitial damage, and causes CKD progression.14 In ADTKD, patients often present with polyuria and accompanying polydipsia due to impaired sodium reabsorption in the kidney and tubular-interstitial damage, increasing fluid loss. The presence of hyposthenuria and polyuria in our patient confirms a reduced capacity of the kidney to concentrate urine.19 The cause of anemia in these patients is also due to decreased renin production, which leads to decreased erythropoietin levels.10 The renin-angiotensin system is involved in erythropoiesis, mainly through angiotensin II, which can stimulate erythroid progenitor cells and increase erythropoietin production. Angiotensin II also directly interacts with hypoxia-inducible factor 1, which regulates erythropoiesis, further stimulating erythropoietin secretion. As a result, the hemoglobin levels are typically between 8 and 11 g/dL in the case of the REN mutation.20

Early diagnosis of ADTKD caused by REN mutations is crucial for implementing targeted interventions that may prevent or delay the progression of CKD. Controlling hyperkalemia, hyperuricemia, metabolic acidosis, correcting anemia, and carefully monitoring kidney function can slow disease progression and preserve kidney function in the long term.21 In our patient, the diagnosis was made at an early age of 1.7 years. Even after a follow-up period of 9 months, appropriate management has already resulted in improved kidney function, demonstrating the benefits of early and targeted intervention. Unlike most other forms of CKD, individuals with REN gene mutations should not be put on a low-sodium diet. Increased sodium intake helps to improve blood pressure and lower serum potassium levels. In addition, fludrocortisone can alleviate the clinical effects of hypoaldosteronism, such as hyperkalemia and acidemia.22 Anemia responded well to erythropoietin treatment, not to iron therapy.23 Although hyperuricemia begins in the infantile period, it can occur in adolescence in untreated cases of gout, which can be easily prevented by daily allopurinol administration.20,22 Since our patient had not yet developed marked hypotension or hyperkalemia, a high-sodium diet or fludrocortisone therapy was not initiated at this stage. Allopurinol, oral sodium bicarbonate and erythropoietin therapies were initiated after the diagnosis. The family was appropriately informed about the chronic nature of the kidney disease, and a lifelong follow-up strategy was established.

This case report has several limitations. The most important of these is that the REN variant identified in the genetic analysis is classified as a VUS. Its pathogenicity has not been definitively established, and there are no functional studies confirming its clinical effect. According to gnomAD, this variant is ultra-rare, with a total allele frequency of 0.00025%, and no homozygous cases have been reported.24 The detailed clinical and laboratory data of this young patient, who is highly consistent with ADTKD, provide valuable information. The high concordance of the patient’s clinical and laboratory features with ADTKD and the ultra-rare nature of the variant strongly suggest that this REN variant may have pathogenic potential. Furthermore, as the report describes a single patient, the findings may not be generalizable to all individuals with the REN mutation. Also, our patient was diagnosed at our center nine months ago and is still being followed; therefore, the relatively short follow-up period limits the assessment of the long-term progression of CKD.

In conclusion, this case underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in the evaluation of infants presenting with persistent anemia and subtle signs of systemic involvement. The coexistence of anemia, hyperuricemia, and elevated serum creatinine—despite an initially unremarkable workup—highlights the multisystemic nature of certain hereditary kidney disorders. Early collaboration between pediatric hematology, nephrology, and genetics was instrumental in establishing the diagnosis, thereby avoiding unnecessary invasive procedures such as a kidney biopsy. Prompt recognition and genetic confirmation of conditions like ADTKD not only allow for targeted interventions—including erythropoietin therapy and uric acid–lowering agents—but also enable appropriate family counseling and long-term disease monitoring. This case illustrates how early and coordinated evaluation across specialties can lead to timely diagnosis, improved clinical outcomes, and a better understanding of disease progression in complex pediatric presentations.

Ethical approval

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patient included in the study for the use of patient data for scientific and academic purposes, provided that the identity information of the patients remained confidential.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Raleigh MF, Yano AS, Shaffer NE. Anemia in infants and children: evaluation and treatment. Am Fam Physician 2024; 110: 612-620.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Monitoring health and health system performance in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: core indicators and indicators on the health-related sustainable development goals 2019. Cairo, Egypt: World Health Organization; 2020. Available at: https://applications.emro.who.int/docs/EMHST245E.pdf

- Gedfie S, Getawa S, Melku M. Prevalence and associated factors of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia among under-5 children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Pediatr Health 2022; 9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X221110860

- Liu Y, Ren W, Wang S, Xiang M, Zhang S, Zhang F. Global burden of anemia and cause among children under five years 1990-2019: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Front Nutr 2024; 11: 1474664. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1474664

- Libudzic-Nowak AM, Cachat F, Pascual M, Chehade H. Darbepoetin alfa in young infants with renal failure: single center experience, a case series and review of the literature. Front Pediatr 2018; 6: 398. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2018.00398

- Endrias EE, Geta T, Israel E, Belayneh Yayeh M, Ahmed B, Moloro AH. Prevalence and determinants of anemia in chronic kidney disease patients in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2025; 12: 1529280. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2025.1529280

- García Díaz FJ, Moreno Ortega M, Beth Martín L, Delgado Pecellín I. Severe anemia in infants: don’t miss the clues. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2023; 62: 1449-1451. https://doi.org/10.1177/00099228231160673

- Shefer Averbuch N, Steinberg-Shemer O, Dgany O, et al. Targeted next generation sequencing for the diagnosis of patients with rare congenital anemias. Eur J Haematol 2018; 101: 297-304. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.13097

- Boer DP, de Rijke YB, Hop WC, Cransberg K, Dorresteijn EM. Reference values for serum creatinine in children younger than 1 year of age. Pediatr Nephrol 2010; 25: 2107-2113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-010-1533-y

- Wilcox WD. Abnormal serum uric acid levels in children. J Pediatr 1996; 128: 731-741. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70322-0

- Farid S, Latif H, Nilubol C, Kim C. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced fanconi syndrome. Cureus 2020; 12: e7686. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7686

- Devuyst O, Olinger E, Weber S, et al. Autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019; 5: 60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0109-9

- Živná M, Kidd KO, Barešová V, Hůlková H, Kmoch S, Bleyer AJ. Autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease: a review. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2022; 190: 309-324. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.32008

- Živná M, Kidd K, Zaidan M, et al. An international cohort study of autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease due to REN mutations identifies distinct clinical subtypes. Kidney Int 2020; 98: 1589-1604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.06.041

- Schaeffer C, Olinger E. Clinical and genetic spectra of kidney disease caused by REN mutations. Kidney Int 2020; 98: 1397-1400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.08.013

- Clissold RL, Clarke HC, Spasic-Boskovic O, et al. Discovery of a novel dominant mutation in the REN gene after forty years of renal disease: a case report. BMC Nephrol 2017; 18: 234. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-017-0631-5

- Ma J, Hu Z, Liu Q, Li J, Li J. Case report: a potentially pathogenic new variant of the REN gene found in a family experiencing autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease. Front Pediatr 2024; 12: 1415064. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2024.1415064

- Cianciolo G, Provenzano M, Hu L, et al. RAASi, MRA and FGF-23 in CKD progression: the usual suspects? Minerva Urol Nephrol 2025; 1-12. https://doi.org/10.23736/S2724-6051.25.06082-3

- Schaeffer C, Izzi C, Vettori A, et al. Autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease with adult onset due to a novel renin mutation mapping in the mature protein. Sci Rep 2019; 9: 11601. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48014-6

- Zivná M, Hůlková H, Matignon M, et al. Dominant renin gene mutations associated with early-onset hyperuricemia, anemia, and chronic kidney failure. Am J Hum Genet 2009; 85: 204-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.07.010

- Econimo L, Schaeffer C, Zeni L, et al. Autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease: an emerging cause of genetic CKD. Kidney Int Rep 2022; 7: 2332-2344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2022.08.012

- Bleyer AJ, Zivná M, Hulková H, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of a family with a dominant renin gene mutation and response to treatment with fludrocortisone. Clin Nephrol 2010; 74: 411-422. https://doi.org/10.5414/cnp74411

- Beck BB, Trachtman H, Gitman M, et al. Autosomal dominant mutation in the signal peptide of renin in a kindred with anemia, hyperuricemia, and CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2011; 58: 821-825. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.06.029

- Global Core Biodata Resource. Genome aggregation database (gnomAD™). SNV:1-204154978-A-G(GRCh38). Available at: https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/variant/1-204154978-A-G?dataset=gnomad_r4 (Accessed on Sep 14, 2025).

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.