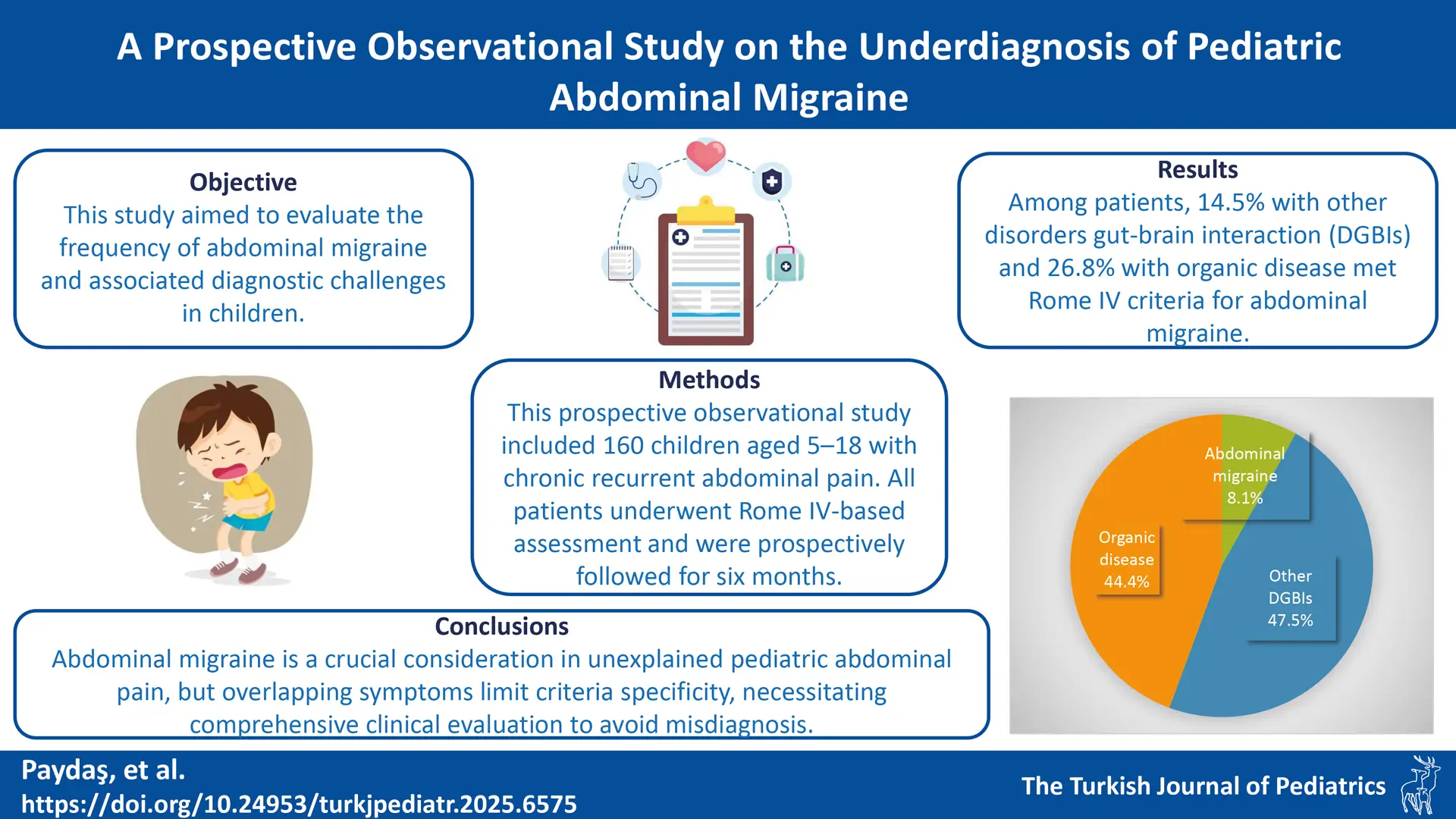

Graphical Abstract

Abstract

Background. Abdominal migraine is often considered a rare cause of chronic abdominal pain in children, but its true prevalence in specialized care and the specificity of current diagnostic criteria are not well understood. We aimed to determine the frequency of abdominal migraine in a tertiary pediatric gastroenterology clinic and to evaluate the diagnostic challenges posed by symptom overlap.

Methods. In this prospective study, 160 children (ages 5–18 years) with chronic recurrent abdominal pain were evaluated and followed for six months. Following comprehensive clinical, laboratory, and endoscopic assessments, patients were assigned to one of three final diagnostic groups: abdominal migraine, other disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI), or organic disease.

Results. The cohort of 160 patients was predominantly female (62.5%; mean age 11.6 ± 4.0 years). Abdominal migraine was the final diagnosis in 8.1% (n=13) of patients. Compared to the other groups, abdominal migraine was characterized by significantly longer pain duration (p = 0.001) and a higher prevalence of stress as a trigger. A key finding was the high rate of diagnostic overlap: 14.5% of patients with other DGBIs and 26.8% of patients with organic disease also fulfilled the Rome IV criteria for abdominal migraine. In these cases, a comprehensive evaluation identified a more appropriate primary diagnosis.

Conclusions. Abdominal migraine is a key diagnosis for unexplained pediatric abdominal pain, but its criteria lack specificity due to symptom overlap. A definitive diagnosis, therefore, requires a thorough clinical evaluation that extends beyond a symptom-based checklist to prevent misdiagnosis.

Keywords: abdominal migraine, abdominal pain, children, functional gastrointestinal disorders, disorders of gut-brain interaction

Introduction

Chronic abdominal pain, defined as at least two episodes of pain severe enough to affect daily activities over two months, is a common pediatric complaint, affecting an estimated 9–15% of children and adolescents.1,2 Given that up to 80% of cases lack a demonstrable organic cause, the diagnosis often falls under disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI).3 DGBIs are understood to arise from complex mechanisms, including visceral hypersensitivity, motility disorders, and dysfunctions in the intestinal sensory and motor systems, with a prevalence ranging from 3–16% depending on the population studied.4,5 The diagnostic framework for these conditions, the Rome criteria, was first established in the 1980s and most recently updated in 2016 as the Rome IV criteria.6

Abdominal migraine, a specific DGBI subtype, occurs in 0.2–4.1% of children.7 It is defined by recurrent, paroxysmal episodes of severe, acute abdominal pain that is typically periumbilical, midline, or diffuse and lasts for at least one hour. These episodes are often accompanied by symptoms such as pallor, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, headache, and photophobia. According to the Rome IV criteria, the symptoms must occur on multiple occasions over at least six months, with a return to baseline health between attacks, and cannot be attributed to another medical condition after a thorough evaluation.8

The impact of DGBIs on children is significant, leading to a lower quality of life, increased school absenteeism, and more frequent hospitalizations, with symptoms persisting into adulthood for up to one-third of patients.9,10 While early diagnosis can mitigate these effects, abdominal migraine remains frequently underdiagnosed.11 Current management is often multimodal, involving psychological therapies, dietary changes, and neuromodulation, reflecting the limited pharmacological options available for children.5This study was therefore designed to determine the frequency of abdominal migraine in children presenting with chronic abdominal pain at a tertiary care clinic. We aimed to highlight its role as an essential differential diagnosis and investigate the factors contributing to its potential underdiagnosis.

Materials and Methods

Study design and data collection

This prospective, cross-sectional study was conducted at a pediatric gastroenterology outpatient clinic between November 2021 and November 2022. The study protocol adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the local institutional ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all legal guardians and assent from participants where appropriate. We prospectively enrolled children aged 5–18 years who presented with chronic, recurrent abdominal pain. Patients were excluded if they had a pre-existing organic disease known to cause abdominal pain, such as inflammatory bowel disease, familial Mediterranean fever, or chronic hepatobiliary or renal conditions.

Over a six-month period, 602 patients were screened for abdominal pain. From this initial pool, 442 were excluded: 26 had inflammatory bowel disease, 328 were being managed for gastritis or gastroesophageal reflux, and 88 had experienced symptoms for less than the required two-month duration. The final study cohort comprised 160 patients with recurrent abdominal pain of at least two months’ duration without a clear organic etiology at enrollment.

Data collection and follow-up

At the initial visit, participants’ guardians completed a structured questionnaire detailing demographic information, clinical symptoms, and family medical history. All patients were evaluated using the Rome IV criteria, and the presence of clinical alarm features (e.g., weight loss, nocturnal symptoms) was documented. Data on comorbid conditions, medication history, and factors reported to trigger or alleviate pain were also collected.

Participants were followed prospectively for six months. During this period, we recorded clinical outcomes, laboratory results, imaging findings, and, when clinically indicated, endoscopic and histopathological data. At the conclusion of the six-month follow-up, a final diagnosis was established for each patient. Based on this diagnosis, patients were stratified into three distinct groups for analysis:

- Group 1: Abdominal migraine

- Group 2: Other DGBIs (e.g., functional dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome)

- Group 3: Organic disease (diagnosed during the follow-up period)

A comparative analysis of demographic, clinical, and diagnostic findings was then performed across these three groups.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses of the study were performed using SPSS 27.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) software. The descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± SD or median (Q1-Q3) for numerical variables as necessary, and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. The normality of the continuous variables was checked by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The comparison between study groups (abdominal migraine, other DGBIs and organic disease) was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD post-hoc test or Kruskal-Wallis test with K-W critical difference pairwise comparison for non-normally distributed variables. Chi-square test was employed to determine the relationships between categorical variables. In all analyses, p < 0.05 value was considered a statistically significant result for 5% type-I error.

Results

Patient demographics and diagnostic stratification

The study cohort comprised 160 pediatric patients with chronic recurrent abdominal pain. The majority were female (62.5%) with a mean age of 11.56 ± 3.98 years (range: 5–18 years) (Table I). After a six-month evaluation, patients were assigned to one of three diagnostic groups (Table II): Group 1 (abdominal migraine; 8.1%, n=13), Group 2 (other DGBIs; 47.5%, n=76), and Group 3 (organic disease; 44.4%, n=71). Patients in Group 3 were significantly older than those in Group 2 (p < 0.001), but no other significant demographic differences were found.

| IBD = Inflammatory bowel disease; SD = Standard deviation; a Q1 = 1st quartile; Q3 = 3rd quartile; b Patients could present with multiple alarm features; therefore, percentages for specific features are calculated from the total cohort (N = 160) and do not sum to 43.1%. | |

| Table I. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort | |

| Characteristic |

|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female |

|

| Male |

|

| Age (years), mean ± SD |

|

| Anthropometric z-scores | |

| Weight, mean ± SD |

|

| Height, mean ± SD |

|

| Body mass index, median [Q1, Q3]a |

|

| Pain localization, n (%) | |

| Periumbilical |

|

| Epigastric |

|

| Widespread |

|

| Other |

|

| Not specified |

|

| Pain duration | |

| Duration (minutes), median [Q1, Q3]a |

|

| Distribution by duration, n (%) | |

| < 1 hour |

|

| 1-72 hours |

|

| > 72 hours |

|

| Alarm features, n (%) | |

| Patients with alarm symptoms |

|

| Specific features reportedb | |

| Family history of IBD, celiac, or peptic ulcer |

|

| Nocturnal diarrhea |

|

| Arthritis symptoms |

|

| Gastrointestinal bleeding |

|

| Growth retardation |

|

| Other (fever, vomiting, weight loss, etc.) |

|

|

a The sum of specific diagnoses may exceed the subtotal for the category as some patients had more than one organic disease; b Helicobacter pylori–positive and –negative gastritis were combined into a single category. NOS: Not otherwise specified. |

||

| Table II. Final diagnoses of patients stratified by category (N = 160) | ||

| Diagnostic category and specific diagnosis |

|

|

| Organic diseasesa |

|

|

| Chronic gastritisb |

|

|

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

|

|

| Celiac disease |

|

|

| Familial Mediterranean fever |

|

|

| Alkaline reflux gastritis |

|

|

| Duodenitis |

|

|

| Lactose intolerance |

|

|

| Disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI) |

|

|

| Functional abdominal pain–NOS |

|

|

| Functional dyspepsia |

|

|

| Irritable bowel syndrome |

|

|

| Abdominal migraine |

|

|

| Functional constipation |

|

|

Pain triggers and alleviating factors

Abdominal pain characteristics of the whole cohort are summarized in Table I. Specific triggers for abdominal pain were identified in 45.0% (n=72) of patients. Dietary factors were the most common trigger (30.6%), with spicy foods, acidic beverages, and fatty foods frequently implicated. Other reported triggers included hunger (4.4%), constipation (4.4%), and stress (3.8%). Factors providing pain relief were reported by 26.3% of patients, with defecation being the most frequent (13.8%), followed by the use of proton pump inhibitors (6.3%).

Medical history and comorbidities

A personal history of migraine was rare (1.9%), but a family history was noted in 26.3% (n=42) of the cohort. Among patients diagnosed with abdominal migraine, none had a personal history of migraine, though 38.5% reported a positive family history. The majority of patients (85.6%) had no comorbid conditions. For the 23 patients with comorbidities, these included allergic/immunological disorders (3.1%), neurological conditions (2.5%), and renal disorders (2.5%). In patients with conditions like familial Mediterranean fever or nephrolithiasis, the chronic abdominal pain was determined to be unrelated to their primary disease.

Laboratory and endoscopic findings

Upper endoscopy was performed in 33.8% (n=54) of patients, prompted by alarm symptoms (n=21) or severe dyspeptic complaints (n=33). Pathological findings were identified in 90.7% (n=49) of these procedures, with erythematous and nodular gastritis being the most common endoscopic abnormalities. Histopathological analysis confirmed chronic gastritis as the most frequent diagnosis. Serological screening for celiac disease via anti-endomysial and anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies yielded positive results in a small number of cases (2.5% and 2.3%, respectively).

Comparative analysis across diagnostic groups

As detailed in Table III, the clinical features of abdominal pain varied significantly across the groups.

| Within a row, values that do not share a common superscript letter (a, b, c) are significantly different from each other based on post-hoc pairwise comparisons (p < 0.05); *p < 0.05 based on the chi-square test; **p < 0.05 based on the Kruskal-Wallis test; DGBI: Disorders of gut-brain interaction; PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; Q1: 1st quartile; Q3: 3rd quartile. | ||||

| Table III. Comparison of abdominal pain characteristics across diagnostic groups. | ||||

| Characteristic |

|

|

|

|

| Localization, n (%) |

|

|||

| Periumbilical |

|

|

|

|

| Epigastric |

|

|

|

|

| Duration of pain (minutes), median [Q1, Q3] |

|

|

|

|

| Duration, categorical, n (%) |

|

|||

| < 1 hour |

|

|

|

|

| 1–72 hours |

|

|

|

|

| Patients with alarm signs, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| Pain triggers, n (%) | ||||

| Eating |

|

|

|

|

| Stress |

|

|

|

|

| Pain relievers, n (%) | ||||

| Defecation |

|

|

|

|

| PPI use |

|

|

|

|

Duration and localization: Pain episodes in the abdominal migraine group (Group 1) were significantly longer than in Groups 2 and 3 (p = 0.001). Pain localization also differed (p < 0.001), with periumbilical pain being most common in the DGBI groups (Groups 1 and 2) and epigastric pain predominating in the organic disease group (Group 3).

Triggers and relief: Pain triggered by eating was significantly less frequent in Group 1, whereas stress-induced pain was more prevalent. Defecation provided relief most often in Group 2, while relief from proton pump inhibitors was a feature of Group 3 (p = 0.001).

Laboratory parameters: No significant differences were observed between groups regarding personal or family history of migraine. A comparison of laboratory parameters revealed statistically significant differences only in aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase levels. However, as all values remained within the normal reference range for children, these findings were not considered clinically significant.

Overlap of diagnostic criteria

A crucial finding was the high percentage of patients in other groups who met the formal criteria for abdominal migraine. Among patients ultimately diagnosed with another DGBI (Group 2) or an organic disease (Group 3), 14.5% and 26.8%, respectively, fulfilled all Rome IV criteria for abdominal migraine. In these patients, the diagnosis of abdominal migraine was ultimately excluded after a comprehensive clinical evaluation identified a more appropriate primary diagnosis.

Discussion

This study offers new insights into the prevalence and diagnostic challenges of abdominal migraine in pediatric patients with chronic abdominal pain. Our findings demonstrate that abdominal migraine accounts for 8.12% of chronic abdominal pain cases in a tertiary care setting, which is notably higher than the 1-4.5% prevalence reported in population-based studies.12 This discrepancy suggests that abdominal migraine may be underdiagnosed in general practice, supporting our hypothesis that this condition is “more than rare” in specialized gastroenterology clinics.

Most significantly, our study reveals critical limitations in the current diagnostic approach. While 15% (n=24) of our cohort initially met Rome IV criteria for abdominal migraine, only 8.12% (n=13) received this final diagnosis after comprehensive clinical evaluation. This finding highlights the need for careful clinical judgment beyond the algorithmic application of symptom-based criteria and raises important questions about their specificity.

Chronic abdominal pain affects an estimated 9-15% of children and adolescents.2 While some studies report higher prevalence in girls aged 9-10 years, others suggest equal sex distribution.13,14,15 A recent Turkish study reported a mean age of 11.26 ± 3.80 years with 67% female predominance.16 Our findings are consistent with these reports, demonstrating 62.5% female predominance and a mean age of 11.5 years.

Patients diagnosed with abdominal migraine in our cohort had a mean age of 10 years, with no significant differences in anthropometric parameters compared to other groups. Although abdominal migraine affects both sexes, literature reports a marked female predominance (1.6:1 ratio) with a prevalence among school-aged children of 1-4.5%.2,12 Previous studies suggest abdominal migraine predominantly affects children aged 3-10 years, with a mean age of 7 years and bimodal peaks at ages 5 and 10.7,17,18 The earlier peak may coincide with school entry as a potential stressor, though the underlying mechanism remains unclear.7

Pain characteristics and duration

While reports of pain duration in abdominal migraine vary from 60 minutes to an average of 17 hours, our results offer important clarification.17,19 We found that pain episodes in our abdominal migraine patients lasted approximately three hours on average significantly longer than in other diagnostic groups. This finding establishes pain duration as a useful distinguishing feature.

Our findings also revealed distinct trigger patterns that may aid in differential diagnosis. Stress was a significantly more prevalent trigger in the abdominal migraine group (30.8%) compared to eating-related pain (7.7%). This pattern suggests that stress sensitivity may be more characteristic of abdominal migraine than dietary sensitivity. While certain foods and stress are known triggers, our data suggest stress may be a more diagnostically significant factor.14,20 Given that anxiety and depression are common in children with functional abdominal pain and that psychological distress increases the likelihood of symptoms persisting into adulthood, these findings emphasize the importance of assessing psychosocial factors.8

Comorbidity patterns and novel associations

In our cohort, 85.6% of patients had no comorbidities. Among those who did, we identified a higher prevalence of renal disease in patients with abdominal migraine a novel finding. A 2022 study linked migraine headaches in children with chronic kidney disease to improved homeostasis post-transplantation.21 Although no direct association with abdominal migraine has been reported, our finding suggests possible shared pathophysiological mechanisms that merit investigation in larger cohorts.

Diagnostic considerations and organic disease prevalence

While organic causes are identified in approximately 5-10% of children with chronic abdominal pain, the majority are diagnosed with functional abdominal pain.22 A Turkish study reported that 68.3% of such patients were diagnosed with functional pain, while 31.7% had an identifiable organic cause after full evaluation.16 Our cohort demonstrated a higher frequency of organic disease (44.37%), which may be attributed to the referral pattern to our gastroenterology clinic, where patients predominantly present with alarm symptoms or suspected organic pathology. This higher organic disease rate in our population strengthens our findings, as it demonstrates that abdominal migraine diagnosis remained robust even in a population with high organic disease prevalence.

Population-based studies indicate that the abdominal migraine phenotype consists of poorly localized, midline, periumbilical (65-80%), or diffuse (16%) pain.12 Pain localization in our study most commonly involved the periumbilical area (69.2%), consistent with previous studies.12,23 However, group-specific differences were noted: patients with abdominal migraine frequently reported diffuse pain, while epigastric pain was more common among those with organic disease. Such findings are consistent with diagnostic criteria for abdominal migraine, which describe pain as periumbilical, midline, or diffuse. The high frequency of gastritis in the organic disease group may explain the predominance of epigastric pain in this subset.

Diagnostic challenges and criteria limitations

Our study has revealed significant diagnostic challenges: a substantial portion of patients with other functional disorders (14.5%) and organic disease (26.8%) met the full Rome IV criteria for abdominal migraine. This reveals significant limitations in the current diagnostic framework. Based on our findings, a definite diagnosis requires more than fulfilling symptom-based criteria. We propose that a definite diagnosis must include: (1) complete exclusion of organic pathology; (2) consideration of the overall clinical picture, not just isolated symptoms; (3) evaluation of response to migraine-specific therapy where appropriate; and (4) longitudinal follow-up to ensure diagnostic stability.

The Rome IV criterion stating that “symptoms cannot be explained by another medical condition after appropriate evaluation” proves crucial but requires careful interpretation. In our experience, this criterion necessitates a comprehensive assessment that goes beyond routine laboratory and imaging studies to include detailed evaluation of psychosocial factors, dietary patterns, and family history.

Our findings suggest that the current Rome IV criteria, while useful as screening tools, lack the specificity required for definitive diagnosis in complex clinical scenarios. This is particularly noteworthy given the established co-occurrence of multiple DGBI in individual patients.24 In these cases, although patients met the abdominal migraine criteria, their primary complaints were attributed to other DGBI. The resulting high rate of false-positive diagnoses (46% of patients meeting criteria did not receive the final diagnosis) indicates that fulfilling diagnostic criteria does not equate to a confirmed diagnosis. We propose that future diagnostic criteria should incorporate stronger emphasis on characteristic pain patterns and duration, more specific requirements for associated symptoms, clearer guidelines for excluding overlapping functional disorders, and integration of family history weighting in diagnostic algorithms.

Impact on clinical management

The diagnosis of abdominal migraine fundamentally alters the therapeutic approach compared to other functional gastrointestinal disorders. While traditional functional abdominal pain management focuses on dietary modifications, stress reduction, and symptomatic treatment, abdominal migraine diagnosis opens avenues for migraine-specific interventions including prophylactic medications, lifestyle modifications targeting migraine triggers, and specialized neurological follow-up.10 In our cohort, patients with abdominal migraine demonstrated distinct clinical patterns: longer pain duration, greater stress sensitivity, and reduced food-related triggers compared to other functional disorders. These characteristics should guide clinicians toward more targeted interventions, including stress management techniques, sleep hygiene optimization, and consideration of migraine prophylaxis in severe cases. On top of that, the diagnosis carries important prognostic implications, as these patients require monitoring for potential evolution to classical migraine during adolescence, with evolution rates ranging from 25-70%.12 This necessitates long-term follow-up strategies that differ significantly from typical functional abdominal pain management protocols.

Relationship with migraine headaches

The relationship between abdominal migraine and classical migraine headaches represents one of the most intriguing aspects of this condition. In a prospective study of school-aged children (5-15 years), approximately 4.1% were diagnosed with abdominal migraine. In particular, children with migraine headaches were twice as likely to experience abdominal migraine, and vice versa.3 Our findings provide additional context to this relationship: among patients with chronic abdominal pain, 1.9% had a personal history of migraine while 26.25% reported a family history of migraine. Family history of migraine was present in 38.46% (n=5) of patients diagnosed with abdominal migraine. This familial clustering is consistent with existing literature, which reports migraine family history in 65-90% of abdominal migraine cases compared to approximately 20% in controls.12

This disconnect between family history and personal migraine history in our abdominal migraine patients suggests several possibilities: (1) abdominal migraine may represent an earlier manifestation of migraine diathesis that precedes headache development, (2) genetic predisposition to migraine may manifest differently in pediatric populations, or (3) current diagnostic approaches may miss subtle migraine headache symptoms in children presenting primarily with abdominal complaints. Therefore, existing studies indicate a high prevalence of family history of migraine among children diagnosed with either abdominal migraine or migraine headaches.25 Based on these data, we suggest that clinicians should inquire about personal and family history of migraines in patients with chronic abdominal pain, which may improve diagnostic accuracy and lead to more effective management.

The concept of abdominal migraine as a “migraine equivalent” or precursor syndrome has important clinical implications. Episodic syndromes associated with migraine—including abdominal migraine, cyclic vomiting syndrome, and infantile colic—are characterized by periodic symptoms in children with positive family histories of migraine and normal interictal neurological examinations.26 These children face an increased risk of developing migraine during adolescence (25-70%, depending on the syndrome).12 Up to 70% of patients later diagnosed with migraine retrospectively report a history of childhood “migraine equivalents,” with abdominal migraine being the most common.27

While literature indicates that 58–70% of children with abdominal migraine also experience migraine headaches, none of our patients had a personal history of migraine, despite a high prevalence of family history. This pattern suggests these children may be in a pre-headache phase of migraine evolution, with important clinical implications: they require neurological monitoring and may benefit from early prevention strategies given their increased risk of developing migraine in adulthood.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. Its questionnaire-based design introduces potential recall bias. Stress, as a trigger of abdominal pain, was assessed subjectively based on patients’ past experiences and was not evaluated using a standardized scale. The single-center, tertiary care setting may limit the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, the small sample size of the abdominal migraine group restricts the statistical power of some observations, such as the association with renal disease, and requires cautious interpretation. Finally, treatment outcomes were not assessed, as the study’s objective was prevalence and characterization.

Clinical implications

This study demonstrates that abdominal migraine is a common and distinct clinical entity. Even when patients meet diagnostic criteria, a thorough evaluation to exclude organic pathology is essential. Clinicians should consider abdominal migraine as a key differential diagnosis in children with persistent abdominal pain, particularly when there is a family history of migraine or a pattern of stress-related triggers. A comprehensive approach integrating clinical history, physical examination, and psychosocial assessment is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Clinical Research Necmettin Erbakan University Ethics Committee (date: January 17, 2022, number: 2022/3837). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Gray L. Chronic abdominal pain in children. Aust Fam Physician 2008; 37: 398-400.

- Niriella MA, Jayasena H, Nishad N, Wijesingha IP, Prabagar K. Abdominal migraine in adults: a narrative review. Cureus 2025; 17: e85958. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.85958

- Di Lorenzo C, Colletti RB, Lehmann HP, et al. Chronic abdominal pain in children: a technical report of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the North American Society for pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2005; 40: 249-261. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mpg.0000154661.39488.ac

- Faure C, Wieckowska A. Somatic referral of visceral sensations and rectal sensory threshold for pain in children with functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Pediatr 2007; 150: 66-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.072

- Thapar N, Benninga MA, Crowell MD, et al. Paediatric functional abdominal pain disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020; 6: 89. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-00222-5

- Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 1262-1279. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032

- Azmy DJ, Qualia CM. Review of abdominal migraine in children. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2020; 16: 632-639.

- Gajendran S, Sharma J, Sharma A. Functional abdominal pain disorders in children. Aust J Gen Pract 2025; 54: 363-366. https://doi.org/10.31128/AJGP-08-24-7369

- de Jesus CD, de Assis Carvalho M, Machado NC. Impaired health-related quality of life in Brazilian children with chronic abdominal pain: a cross-sectional study. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 2022; 25: 500-509. https://doi.org/10.5223/pghn.2022.25.6.500

- Sinopoulou V, Groen J, Gordon M, et al. Efficacy of interventions for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome, functional abdominal pain-not otherwise specified, and abdominal migraine in children: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2025; 9: 315-324. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(25)00058-6

- Uc A, Hyman PE, Walker LS. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in African American children in primary care. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006; 42: 270-274. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mpg.0000189371.29911.68

- Irwin S, Barmherzig R, Gelfand A. Recurrent gastrointestinal disturbance: abdominal migraine and cyclic vomiting syndrome. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2017; 17: 21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0731-4

- Malaty HM, Abudayyeh S, Fraley K, Graham DY, Gilger MA, Hollier DR. Recurrent abdominal pain in school children: effect of obesity and diet. Acta Paediatr 2007; 96: 572-576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00230.x

- Devanarayana NM, Mettananda S, Liyanarachchi C, et al. Abdominal pain-predominant functional gastrointestinal diseases in children and adolescents: prevalence, symptomatology, and association with emotional stress. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011; 53: 659-665. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182296033

- Dhroove G, Saps M, Garcia-Bueno C, Leyva Jiménez A, Rodriguez-Reynosa LL, Velasco-Benítez CA. Prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in Mexican schoolchildren. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2017; 82: 13-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rgmx.2016.05.003

- Vatansever G, Tanca AK, Kırsaçlıoğlu CT, Demir AM, Kuloğlu Z. Evaluation of children with chronic abdominal pain and cost analysis. J Ankara Univ Fac Med 2021; 74: 324-331. https://doi.org/10.4274/atfm.galenos.2021.93585

- Winner P. Abdominal migraine. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2016; 23: 11-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spen.2015.09.001

- Abu-Arafeh I, Russell G. Prevalence and clinical features of abdominal migraine compared with those of migraine headache. Arch Dis Child 1995; 72: 413-417. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.72.5.413

- Evans RW, Whyte C. Cyclic vomiting syndrome and abdominal migraine in adults and children. Headache 2013; 53: 984-993. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12124

- Escobar MA, Lustig D, Pflugeisen BM, et al. Fructose intolerance/malabsorption and recurrent abdominal pain in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014; 58: 498-501. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000000232

- Elron E, Davidovits M, Eidlitz Markus T. Headache in pediatric and adolescent patients with chronic kidney disease and after kidney transplantation: a comparative study. J Child Neurol 2022; 37: 497-504. https://doi.org/10.1177/08830738221086432

- Wright NJ, Hammond PJ, Curry JI. Chronic abdominal pain in children: help in spotting the organic diagnosis. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2013; 98: 32-39. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-302273

- Wilder-Smith CH, Schindler D, Lovblad K, Redmond SM, Nirkko A. Brain functional magnetic resonance imaging of rectal pain and activation of endogenous inhibitory mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome patient subgroups and healthy controls. Gut 2004; 53: 1595-1601. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2003.028514

- Van Tilburg MA, Walker LS, Palsson OS, et al. 820 prevalence of child/adolescent functional gastrointestinal disorders in a national US Community Sample. Gastroenterology 2014 ; 146: 143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(14)60508-4

- Napthali K, Koloski N, Talley NJ. Abdominal migraine. Cephalalgia 2016; 36: 980-986. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102415617748

- Aurora SK, Shrewsbury SB, Ray S, Hindiyeh N, Nguyen L. A link between gastrointestinal disorders and migraine: Insights into the gut-brain connection. Headache 2021; 61: 576-589. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14099

- LenglarT L, Caula C, Moulding T, Lyles A, Wohrer D, Titomanlio L. Brain to belly: abdominal variants of migraine and functional abdominal pain disorders associated with migraine. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021; 27: 482-494. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm20290

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.