Abstract

Background. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm of intermediate malignant potential, commonly arising in the lungs and intra-abdominal organs. Involvement of the urinary bladder is exceptionally rare, particularly in children, and may clinically and radiologically mimic malignant tumors.

Case Presentation. We report the case of a 10-year-old girl who presented with painless macroscopic hematuria and syncope, necessitating blood transfusion. Initial imaging revealed a bladder mass, and biopsy initially suggested rhabdomyosarcoma. Definitive histopathological evaluation, however, confirmed IMT. Partial cystectomy was performed, but due to positive surgical margins and recurrent hematuria, targeted therapy with crizotinib was initiated based on anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) positivity. At 12-month follow-up, the patient remained symptom-free with no evidence of recurrence on imaging.

Conclusion. Pediatric IMT of the bladder is a rare but important differential diagnosis for bladder masses. Accurate histological diagnosis is essential, as this tumor may mimic malignancy and influence the treatment plan. Complete surgical excision remains the cornerstone of treatment, while targeted therapies such as ALK inhibitors offer valuable options in cases with residual disease or risk of recurrence. This case highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach involving surgery, pathology, and oncology. Further pediatric-focused studies are warranted to refine treatment strategies and define long-term outcomes.

Keywords: soft tissue neoplasm, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, urinary bladder mass, children, crizotinib

Introduction

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm primarily affecting children and young adults, with intermediate malignant potential and variable histology and behavior.1 Because IMT can arise at multiple sites and shows heterogeneous histologic and radiologic features – with behavior ranging from spontaneous regression to local recurrence and rare metastasis – it remains incompletely understood.2 It can occur anywhere in the body, but it is most commonly detected in the lung, retroperitoneum, and gastrointestinal tract.3 Approximately 9.5% of extrapulmonary IMTs arise in the genitourinary system, most commonly in the bladder.4

Symptoms vary depending on the location and size. It is estimated that one-third of IMT patients present with systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, growth retardation, or anemia. Definitive management generally involves complete resection; however, when complete excision is not feasible, systemic therapies may be considered. Over the past decade, advances in tumor biology and molecular genetics have refined the characterization of IMT and enabled the development of targeted therapies. However, important uncertainties persist regarding optimal management.

Masses of the urinary bladder are rarely seen in pediatric age groups, which often poses significant diagnostic challenges and necessitates histological differentiation and confirmation. This case report contributes to the limited literature on pediatric IMTs of the bladder by describing a rare pediatric case successfully treated with partial cystectomy and targeted anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibition, highlighting the role of a multidisciplinary approach and the potential of organ-sparing strategies. We present a case of a 10-year-old girl with painless gross hematuria caused by an IMT of the bladder (IMTB).

Case Presentation

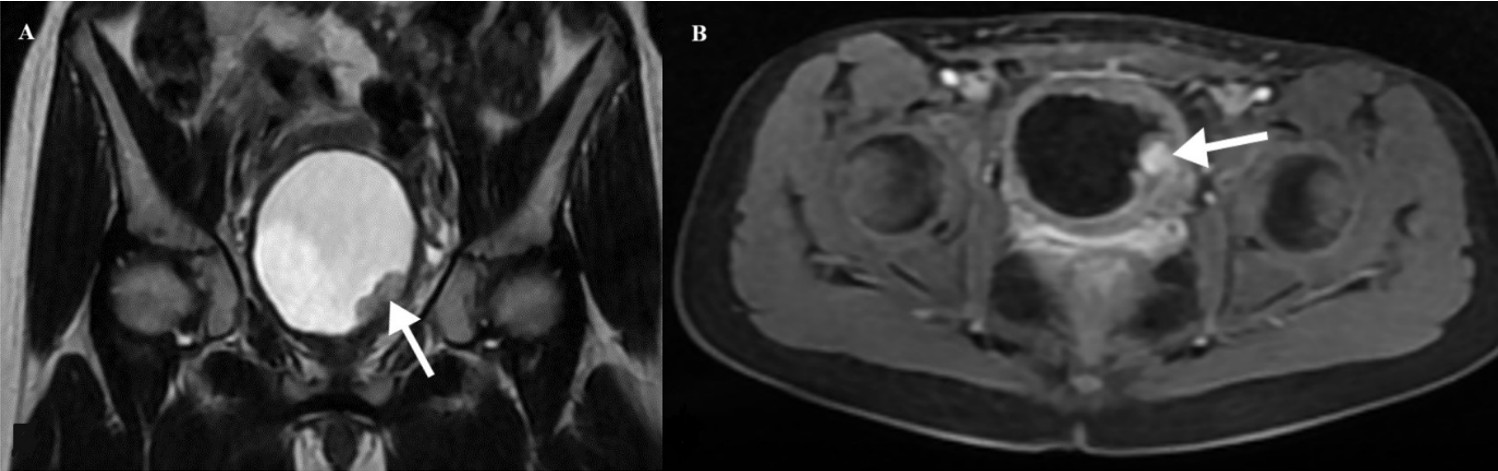

A 10-year-old girl was admitted to another hospital presenting with painless gross hematuria that led to syncope and required transfusion. Ultrasonography (US) revealed a well-circumscribed mass located at the base of the bladder. Due to uncontrollable hematuria, a palliative laparotomy was performed at another hospital. A biopsy of the bladder mass, initially suspected to represent rhabdomyosarcoma, was subsequently diagnosed as an IMT upon histopathological evaluation. The patient was then referred to our institution for further evaluation and management. The patient’s medical history was otherwise unremarkable, and both physical examination and hematologic evaluations—including complete blood count, coagulation profile, and basic serum chemistry—were within normal limits. Abdominal US showed a well-defined hypoechoic lesion measuring 30×20 mm at the bladder base, without calcification. Color Doppler imaging demonstrated mild vascularization within the lesion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a contrast-enhanced solid mass measuring 20×23×30 mm in the left posterolateral bladder wall, near the bladder neck (Fig. 1). On cystoscopy, the right ureter orifice was visualized, but the left orifice was obscured by a protruding mass on the left bladder wall extending toward the bladder neck.

The patient underwent a partial cystectomy, preserving both ureters and the trigone. Because the diagnosis had already been established by biopsy, surgical excision was performed with the goal of preserving bladder function and the left ureter. The postoperative course was uneventful, with no complications.

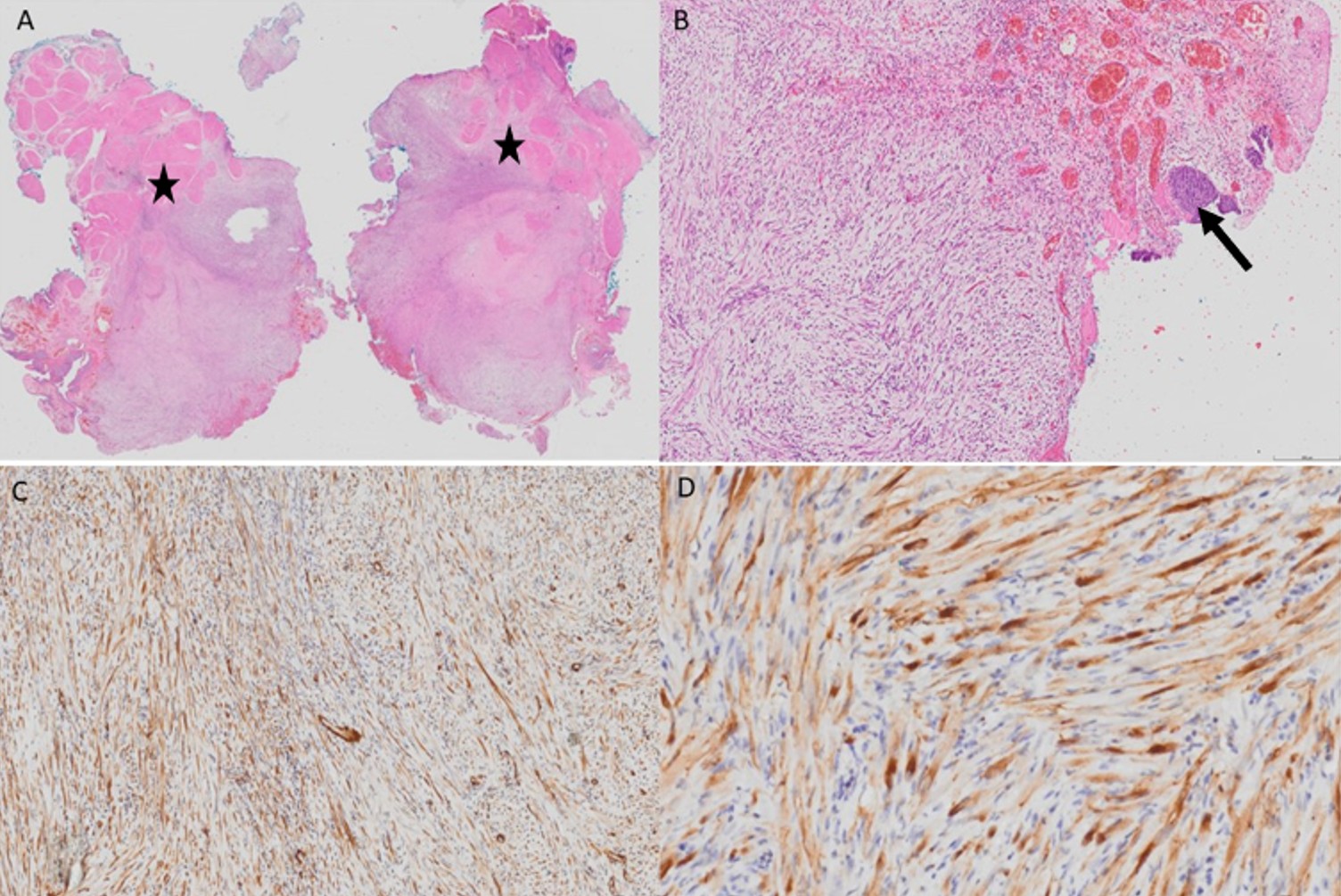

The diagnosis of IMT was confirmed by histopathological examination. Surgical margins were positive. Immunohistochemical analysis showed patchy staining with smooth muscle actin (SMA), focal weak ALK positivity, and negative staining for desmin. Immunostaining for myogenic differentiation 1 (MyoD1) and myogenin was non-specific. The Ki-67 proliferation index was approximately 5% (Fig. 2).

The patient was followed for six months without additional treatment. She later developed recurrent hematuria, prompting a repeat MRI. Minimal nonspecific bladder wall thickening was observed. There was no evidence of recurrence. Crizotinib therapy was initiated due to persistent symptoms and positive surgical margins. She received crizotinib for ten months. Hematuria resolved with crizotinib and after one year follow-up there was no evidence of disease recurrence.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian for publication of this case and accompanying images.

Discussion

IMTs are rare mesenchymal neoplasms, most commonly occurring in the lungs and intra-abdominal organs, though they can also arise in genitourinary structures such as the bladder. In children, IMTB is exceptionally rare and requires a multidisciplinary diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Their unpredictable clinical behavior - ranging from benign to locally aggressive forms - underscores the importance of comprehensive diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

The clinical presentation of IMT varies according to tumor site. In IMTB, the most common symptoms are hematuria, dysuria, and obstructive voiding complaints. Because these symptoms can mimic both benign and malignant bladder lesions, imaging and histopathological confirmation are essential. In our case, the patient presented with painless gross hematuria resulting in syncope and requiring transfusion, a rare and severe manifestation of IMTB.

Definitive diagnosis is established through histopathologic examination and immunohistochemical analysis. The hallmark histologic features of IMT include spindle cell proliferation accompanied by a prominent inflammatory infiltrate composed of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils.5 Immunohistochemical staining for ALK, smooth muscle actin, and desmin helps differentiate IMT from other spindle cell neoplasms. Our case showed patchy SMA positivity, focal weak ALK positivity, and negative staining for desmin, with a Ki-67 proliferation index of approximately 5%, findings consistent with previously reported cases of IMTB.5 The underlying etiology of IMTB remains unclear. Proposed contributing factors include infection, prior instrumentation, trauma, and immunosuppression, which may induce an exaggerated inflammatory response leading to myofibroblastic proliferation.2,4 Genetic alterations are also thought to play a key role in the pathogenesis of IMT. Recent molecular studies have shown that IMTs are associated with ALK gene rearrangements in approximately 50-70% of cases.6 In pediatric IMTBs, ALK-positivity serves as an important biomarker that guides treatment decisions. Conversely, ALK-negative tumors, tend to follow a more aggressive course and may require alternative therapeutic strategies. Other genetic alterations, including ROS1 and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRB) rearrangements, have also been identified in a subset of IMT, representing potential targets for novel therapies.7

The surgical management of IMTB differs from that of malignant bladder tumors, in which radical or extensive resections are often required. IMTB is generally regarded as a tumor of intermediate malignant potential, characterized by a propensity for local recurrence and rare metastatic spread. Consequently, organ-sparing surgery is typically favored whenever feasible. Preoperative or intraoperative biopsy plays a pivotal role in establishing the diagnosis, enabling the surgical team to tailor the procedure and avoid unnecessary radical interventions. Early histological confirmation facilitates a conservative, function-preserving approach focused on complete local excision, which is particularly important in pediatric patients, for whom bladder preservation and minimizing morbidity are key priorities.4,8,9 Surgical resection remains the primary treatment option for patients with localized IMT. Although IMT is generally considered a tumor of intermediate malignant potential, distant metastases and local recurrences have been reported in some cases. Reported local recurrence rates in large pediatric series range from 15% to 37%.8 However, as demonstrated in the present case partial excision can be appropriate option when organ involvement may compromise vitality, quality of life, and function. When surgical margins are positive or complete resection is not feasible, additional therapeutic strategies may be required. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibitors such as crizotinib and alectinib have shown promising results in ALK-positive IMT, offering an effective organ-sparing, non-surgical alternative.10 While surgical resection remains the cornerstone of treatment for IMTB, avoiding unnecessary radical or morbid procedures is of particular importance in pediatric patients. In recent years, systemic therapy with ALK inhibitors has emerged as a valuable adjunct, especially in patients with ALK-positive tumors. Preoperative use of ALK inhibitors can reduce tumor burden, facilitate less invasive, organ-sparing surgery, and minimize perioperative morbidity. This strategy has been reported to achieve good local control and preserve bladder function in selected cases.8,10,11

In pediatric IMTB, there is a growing trend toward organ-sparing surgical strategies supported by molecularly targeted therapies, rather than extensive resections that may lead to long-term morbidity. Pediatric case series have demonstrated that limited surgery combined with close follow-up or ALK inhibitor therapy, when indicated, can provide excellent local control and preserve bladder function. The preoperative or primary use of ALK inhibitors in selected ALK-positive cases may reduce tumor size, facilitate conservative surgery, and help avoid radical interventions. This underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary treatment approach that integrates pediatric surgery, pathology, radiology, and oncology to achieve optimal outcomes in this rare disease.8-11

Our patient initially underwent postoperative surveillance but subsequently developed recurrent hematuria, prompting an MRI evaluation, which revealed minimal nonspecific bladder wall thickening without evidence of recurrence. Owing to her persistent symptoms and positive margins, crizotinib therapy was initiated, resulting in complete resolution of hematuria and no evidence of disease recurrence at one-year follow-up. This observation is consistent with previous reports demonstrating the efficacy of crizotinib in achieving remission in ALK-positive IMTs.10

Although Ki-67 is not a validated or standardized criterion for guiding treatment decisions in IMTB, the proliferative index can provide valuable adjunctive information regarding tumor biology. In IMT, lower Ki-67 levels have been associated with a more indolent clinical course, whereas higher proliferative activity has been reported in more aggressive cases.12,13 Similar trends have been robustly demonstrated across multiple solid tumors: in renal cell carcinoma, prostate cancer, and bladder cancer, elevated Ki-67 expression correlates with adverse pathological features and significantly worse survival outcomes.14-16 These data collectively support the use of Ki-67 as an adjunctive marker of biological behavior, while emphasizing that it should not be used as a stand-alone criterion to guide management decisions.7,9

In addition to our case, several ALK-positive pediatric IMTB have been reported in the literature, providing valuable insights into their clinical course and therapeutic options. Beland et al. reported a three-case pediatric series in which patients demonstrated favorable responses to either targeted ALK inhibition or surgical resection, with durable disease control during follow-up.9 Similarly, Fujiki et al. reported a pediatric patient with a fibronectin 1–ALK fusion who achieved complete remission following treatment with the ALK inhibitor alectinib.11 Earlier molecular studies by Antonescu et al. identified ALK gene rearrangements as the most common molecular driver in IMTs, supporting the rationale for targeted therapy in selected cases.7 Collectively, these reports indicate that ALK-positive IMTB typically presents with localized disease and shows responses to ALK inhibitors, particularly in cases with residual or unresectable tumors, offering a potentially effective organ-sparing alternative to radical surgery.

The optimal duration of crizotinib therapy in pediatric IMTB remains undefined. Previous reports have demonstrated treatment durations ranging from 12 to 24 months, with most patients achieving clinical and radiological responses within the first few months of therapy.9,10,17 In our case, the patient achieved sustained remission after 10 months of treatment, consistent with previously reported outcomes.

While IMTs generally have a favorable prognosis, recurrence rates vary depending on tumor localization, histological features, and completeness of resection. A study on recurrent IMT reported that IMTB may recur after transurethral resection, particularly in the presence of positive surgical margins or incomplete excision, underscoring the need for long-term follow-up.18 Close post-treatment surveillance with periodic imaging is recommended to detect early recurrence and to guide subsequent management. Incorporating molecular profiling into treatment planning allows for a more personalized therapeutic approach, potentially optimizing outcomes for pediatric patients with IMT.

This case report is limited by its single-case nature and the relatively short follow-up duration of 12 months, which may not allow for a comprehensive assessment of recurrence risk. Extended clinical and radiologic surveillance will be important to detect late recurrences and evaluate the long-term efficacy of targeted therapy.

Conclusion

Pediatric IMTBs are rare tumors that require thorough clinical and pathological characterization to inform appropriate treatment strategies. The presence of ALK mutations significantly impacts therapeutic decision-making, underscoring the importance of targeted therapies in conjunction with surgical interventions. When feasible, complete excision should be pursued, otherwise, organ- and function-sparing approaches may be considered. This case highlights the critical role of early diagnosis, tailored surgical management, and targeted therapy in the setting of residual disease, illustrating the potential of crizotinib to achieve durable disease control. Advances in molecular diagnostics and targeted therapies offer promising opportunities for optimizing management, particularly in recurrent or unresectable cases. Future studies with larger patient cohorts are needed to further clarify disease pathogenesis, refine molecular classification, and define evidence-based treatment algorithms for pediatric IMTs.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardians.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Rich BS, Fishbein J, Lautz T, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a multi-institutional study from the Pediatric Surgical Oncology Research Collaborative. Int J Cancer 2022; 151: 1059-1067. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.34132

- Zhao JJ, Ling JQ, Fang Y, et al. Intra-abdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: spontaneous regression. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 13625-13631. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i37.13625

- Inamura K, Kobayashi M, Nagano H, et al. A novel fusion of HNRNPA1-ALK in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of urinary bladder. Hum Pathol 2017; 69: 96-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2017.04.022

- Montgomery EA, Shuster DD, Burkart AL, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the urinary tract: a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases, including a malignant example inflammatory fibrosarcoma and a subset associated with high-grade urothelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30: 1502-1512. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pas.0000213280.35413.1b

- Jang EJ, Kim KW, Kang SH, Pak MG, Han SH. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors arising from pancreas head and peri-splenic area mimicking a malignancy. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2021; 25: 287-292. https://doi.org/10.14701/ahbps.2021.25.2.287

- Lowe E, Mossé YP. Podcast on emerging treatment options for pediatric patients with ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Oncol Ther 2024; 12: 247-255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-024-00275-6

- Antonescu CR, Suurmeijer AJH, Zhang L, et al. Molecular characterization of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors with frequent ALK and ROS1 gene fusions and rare novel RET rearrangement. Am J Surg Pathol 2015; 39: 957-967. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000404

- Nagumo Y, Maejima A, Toyoshima Y, et al. Neoadjuvant crizotinib in ALK-rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the urinary bladder: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2018; 48: 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.04.027

- Beland LE, Van Batavia JP, Mittal S, Kolon TF, Surrey LF, Long CJ. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the bladder in childhood: a three case series. Urology 2025; 200: e72-e75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2025.02.045

- Kaino A, Niizuma H, Katayama S, et al. Two-year crizotinib monotherapy induced durable complete response of pediatric ALK-positive inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2023; 70: e30330. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.30330

- Fujiki T, Sakai Y, Ikawa Y, et al. Pediatric inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the bladder with ALK-FN1 fusion successfully treated by alectinib. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2023; 70: e30172. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.30172

- Dobrosz Z, Ryś J, Paleń P, Właszczuk P, Ciepiela M. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the bladder - an unexpected case coexisting with an ovarian teratoma. Diagn Pathol 2014; 9: 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-9-138

- Buccoliero AM, Ghionzoli M, Castiglione F, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular features of a pediatric case. Pathol Res Pract 2014; 210: 1152-1155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2014.03.011

- Xie Y, Chen L, Ma X, et al. Prognostic and clinicopathological role of high Ki-67 expression in patients with renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 44281. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44281

- Berlin A, Castro-Mesta JF, Rodriguez-Romo L, et al. Prognostic role of Ki-67 score in localized prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol Oncol 2017; 35: 499-506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.05.004

- Tian Y, Ma Z, Chen Z, et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic value of Ki-67 expression in bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0158891. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158891

- Schöffski P, Kubickova M, Wozniak A, et al. Long-term efficacy update of crizotinib in patients with advanced, inoperable inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour from EORTC trial 90101 CREATE. Eur J Cancer 2021; 156: 12-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2021.07.016

- Alene AT, Tamir KT, Melaku A, Teka MD, Desalew ED. Recurrent inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMTs) of bladder managed with transurethral resection; case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2025; 128: 110978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2025.110978

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.