Graphical Abstract

Abstract

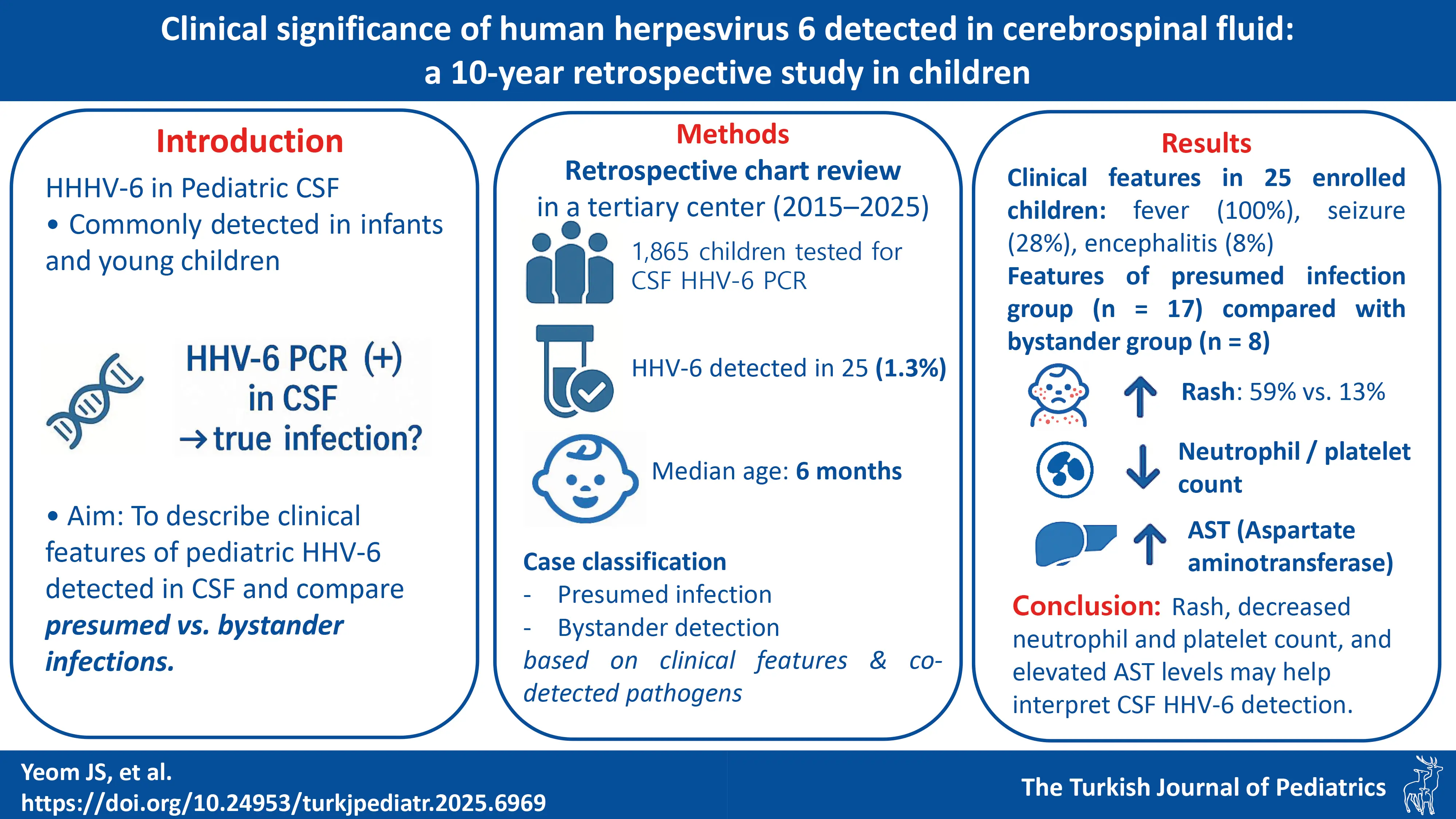

Background. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is occasionally detected in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of young children, but its clinical significance remains uncertain. This study aimed to describe HHV-6–positive cases and to explore features that may help distinguish presumed infection from bystander detection.

Methods. We retrospectively reviewed pediatric patients with CSF HHV-6 detected by multiplex polymerase chain reaction or the FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis (FA-ME) panel between January 2015 and March 2025 at a single tertiary hospital. Cases were categorized as presumed HHV-6 infection or bystander detection based on clinical features and the presence of alternative pathogens or diagnoses. Clinical and laboratory findings were compared between the two groups.

Results. Among 1,865 children tested, HHV-6 was detected in 25 (1.3%; median age, 6 months), all of whom presented with fever. Seizures occurred in seven (28%) and ataxia in one (4%). Two patients developed encephalitis; one had abnormal imaging and later developed epilepsy. Seventeen patients were classified as presumed infection. In this group, rash was more prevalent (59% vs. 13%, p = 0.04), neutrophil and platelet counts were lower at admission and declined further at follow-up (p < 0.05), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were higher (p < 0.01) than those in the bystander infection group. CSF pleocytosis did not differ significantly between groups. Two patients received ganciclovir; both had HHV-6 detected early by the FA-ME panel, and one was subsequently diagnosed with bacterial sepsis.

Conclusions. HHV-6 encephalitis was uncommon. Rash, changes in neutrophil and platelet counts, along with elevated AST levels may help interpret CSF HHV-6 detection, but these findings require validation in larger studies incorporating virologic confirmation.

Keywords: human herpesvirus 6, cerebrospinal fluid, exanthema, cytopenia

Introduction

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) infection is a common viral infection in early childhood.1 Primary infection in this age group is usually symptomatic, and children often present with high fever or seizures, requiring medical evaluation.2,3 Incidence peaks between 6 and 9 months, but approximately 20% of infections occur in infants aged < 6 months, in whom fever warrants particular clinical attention.4 HHV-6 infection in most children resolves spontaneously; however, this virus may occasionally cause serious neurological complications such as encephalitis, even in immunocompetent children.5 These observations suggest that HHV-6 infection poses a considerable clinical burden during early childhood.

The hallmark presentation of HHV-6 is exanthem subitum, characterized by several days of high fever followed by an abrupt rash.6 When this characteristic rash is absent, diagnosis can be challenging, particularly in young febrile infants.7 The recent adoption of the FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis (FA-ME) panel has enabled rapid detection within hours, which is significantly faster than traditional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods.8 While this technological advancement improves diagnostic efficiency, careful clinical judgment is required because interpreting the significance of HHV-6 detection in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) remains challenging.8 Absence of CSF pleocytosis is frequently reported in HHV-6–associated neurological presentations, including encephalitis.9 In addition, the presence of HHV-6 DNA does not always indicate a primary infection. It may instead reflect viral reactivation or chromosomal integration. HHV-6 is unique among human herpesviruses because it can be integrated into host chromosomes,10 often through germline transmission. This process can lead to persistently high levels of viral DNA in the serum, whole blood, and occasionally CSF, even without active replication.11 In a study of CSF samples from 200 children < 2 years old with suspected CNS infection, HHV-6 DNA was detected in 2.5% of cases with primary infection and in 2.0% with chromosomally integrated HHV-6.11 In that study, HHV-6 DNA was not detected in the CSF of children aged > 2 years or adults as a result of primary infection.11 These findings suggest that only about half of the HHV-6 DNA detected in the CSF of children aged < 2 years reflects true primary infection and that HHV-6 DNA detection may not indicate primary infection in older individuals.11 These results highlight the need for caution when interpreting HHV-6 detection in CSF. Furthermore, chromosomally integrated HHV-6 (ciHHV-6) can be identified through persistently high viral loads or by detecting viral DNA in hair follicles;1 however, these approaches may not be practical for clinical use. Therefore, clinical markers are required to help interpret HHV-6 detection in CSF; however, currently, such information is limited.

The aim of this study was to enhance clinical understanding by retrospectively reviewing pediatric cases of HHV-6 detected in CSF over the past decade. The primary objective was to describe the clinical features of these pediatric cases in detail. As a secondary objective, we analyzed the clinical differences between cases in which HHV-6 was presumed to be pathogenic and those in which it was considered unlikely to reflect active infection.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the authors’ institution, and informed consent was waived because of its retrospective design.

Study design

This study was conducted at the Gyeongsang National University Hospital (a tertiary center with approximately 900 inpatient beds), serving Gyeongnam province in South Korea. We retrospectively analyzed the laboratory data of children with CSF specimens sampled by lumbar puncture and tested by multiplex PCR for six human herpesviruses (herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 [HSV-1 and -2], Epstein–Barr virus [EBV], cytomegalovirus [CMV], HHV-6, and varicella-zoster virus [VZV]) or the FA-ME panel as part of standard clinical care between January 2015 and March 2025. The FA-ME panel, which was adopted by our institution in 2021, detects 14 pathogens, including six bacteria (Escherichia coli K1, Haemophilus influenzae, Listeria monocytogenes, Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus agalactiae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae), seven viruses (CMV, enterovirus, HSV-1 and -2, HHV-6, human parechovirus, and VZV), and one fungus (Cryptococcus neoformans/gattii).

Data collection

Clinical data of children with HHV-6 positive results were obtained through a medical chart review. Data regarding age, sex, clinical presentation or symptoms, fever duration, presence of rash, antimicrobial therapy, and radiographic findings were obtained. Results of additional infectious disease testing of CSF and other clinical specimens were also reviewed to determine alternative infectious etiologies. CSF parameters, including white blood cell (WBC) count, protein and glucose levels, were also collected. Other laboratory findings, including WBC count, platelet count, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, were recorded.

Investigation for HHV-6 positivity

To interpret HHV-6 positivity in CSF samples, we conducted a detailed chart review. Patients were classified into presumed HHV-6 infection or presumed bystander detection. Presumed infection cases were defined as those in which the clinical presentation strongly suggested HHV-6 as the most plausible cause of illness, while recognizing that definitive virological proof (e.g., viral load quantification or serology) was not available. Presumed bystander cases were those in which HHV-6 detection was considered incidental or better explained by another pathogen or clinical condition.

A diagnosis of presumed HHV-6 infection was made when one of the following criteria was met: 1) a typical HHV-6 illness of 3–4 days of high fever followed by a roseola-like rash or 2) in the absence of other identifiable pathogens, clinical features compatible with HHV-6 infection, such as a roseola-like rash following fever shorter than the typical 3-4 days, febrile seizures in children aged < 2 years, meningitis or encephalitis with CSF pleocytosis, or unexplained fever in infants aged < 6 months. The bystander group included patients who did not meet the above criteria, or in whom alternative pathogens more plausibly accounted for the illness. All cases were independently reviewed by a pediatric neurologist and a pediatric infectious disease specialist who were directly involved in the clinical care of these patients, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Analysis

To identify distinguishing features of clinically significant cases, we compared the infection and bystander groups by sex, age, fever duration, presence of rash, seizure occurrence, CSF profile, and laboratory findings. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test and the Mann–Whitney U test. For each variable, the relative difference (RD) was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to estimate effect size. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Patient testing and prevalence of HHV-6

Multiplex PCR testing for six human herpesviruses was performed in 1,665 patients. In addition, 232 patients were tested using the FA-ME panel, which has been implemented in clinical practice since August 2021. Among them, 32 patients underwent both tests, resulting in a total of 1,865 pediatric patients being tested. Of these, HHV-6 was detected in 25 patients (1.3%).

Characteristics of HHV-6-positive patients

Table I shows the clinical characteristics of HHV-6-positive patients (n = 25). The median age was 6 months (interquartile range [IQR], 2–18 months), and the majority were male (56%, n = 15). All patients presented with fever, and seizures occurred in seven (28%). Of these, five had recurrent seizures, and two experienced only a single event. Ataxia was observed in one patient (4%). CSF pleocytosis (≥5 WBC/µL) was identified in 11 patients (44%). HHV-6 was detected by the FA-ME panel in 5 patients and by multiplex PCR in 20. All participants were previously documented as healthy; however, no records of a systematic assessment of immune function were available. None had a history of receiving immunosuppressive therapy, including corticosteroids.

| CMV, cytomegalovirus; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; HHV-6, human herpes virus-6; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; N/d, not done; WBC, white blood cell; * Multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for respiratory viruses, including adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, human bocavirus, human metapneumovirus, human coronavirus, rhinovirus, and enterovirus; † Multiplex PCR for acute gastroenteritis pathogens, including astrovirus, adenovirus, rotavirus, norovirus, Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter coli, Clostridium perfringens, Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio vulnificus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., Bacillus cereus, Yersinia enterocolitica, Staphylococcus aureus, and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli; ‡ Cerebrospinal fluid was tested using a FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis panel, which detects Escherichia coli K1, CMV, enterovirus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, HHV-6, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV-1/2), Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus agalactiae, Cryptococcus neoformans/gattii, Haemophilus influenzae, varicella zoster virus (VZV), Listeria monocytogenes, and human parechovirus; otherwise tested with multiplex PCR for herpesviruses including HSV-1/2, VZV, EBV, CMV, and HHV-6; § presumed bystander HHV-6 | |||||||||||||

| Table I. Summary of clinical findings for patients with HHV-6 detected in cerebrospinal fluid. | |||||||||||||

| No. of patient | Sex | Age (mo) | Symptoms | Fever duration (days) | Rash | CSF WBC (/µL) |

CSF glucose (mg/dL) | CSF protein (mg/dL) | Blood HHV-6 | Other possible pathogens | Empirical / specific treatment | Brain imaging | Complication |

| 1 | F | 7 | Fever, seizures | 4 | + | 8 | 74 | 188 | + | None* | Acyclovir, IVIG, antibiotics / maintained | Focal hemorrhage, pons, midbrain and both lower thalami. | Epilepsy |

| 2 | M | 11 | Fever, seizures | 5 | + | 2 | 64 | 11 | + | None*† | None / none | Normal | None |

| 3 | F | 12 | Fever, seizures | 2 | - | 0 | 69 | 12 | + | None* | None / none | N/d | None |

| 4 | M | 18 | Fever, seizures | 4 | - | 0 | 72 | 21 | + | None*† | Antibiotics / none | Normal | None |

| 5 | M | 18 | Fever, seizures | 5 | + | 0 | 65 | 17 | + | Adenovirus* | Antibiotics / none | Normal | None |

| 6 | F | 11 | Fever, single seizure | 2 | - | 0 | 78 | 53 | N/d | None* | None / none | N/d | None |

| 7 | M | 6 | Fever, a single seizure | 3 | + | 5 | 68 | 28 | + | None* | Antibiotics / none | N/d | None |

| 8 | M | 2 | Fever, lethargy | 2 | - | 792 | 58 | 118 | + | None* | Antibiotics / none | Normal | None |

| 9‡ | M | 18 | Fever, ataxia | 4 | + | 1 | 57 | 26 | N/d | None* | Antibiotics / none | Normal | None |

| 10‡ | F | 36 | Fever, headache, lethargy | 5 | - | 23 | 54 | 24 | - | None*† | Antibiotics, IVIG / ganciclovir | Normal | None |

| 11 | M | 1 | Fever | 1 | + | 1 | 57 | 45 | - | None*† | Antibiotics / none | N/d | None |

| 12 | F | 2 | Fever | 3 | + | 6 | 64 | 27 | N/d | None* | Antibiotics / none | N/d | None |

| 13 | M | 3 | Fever | 1 | - | 0 | 62 | 24 | + | None* | Antibiotics / none | N/d | None |

| 14 | M | 5 | Fever | 4 | + | 2 | 70 | 68 | N/d | None* | Antibiotics | N/d | None |

| 15 | F | 26 | Fever | 7 | + | 0 | 53 | 31 | + | None*† | Antibiotics / none | N/d | None |

| 16 | F | 6 | Fever, lethargy | 1 | + | 1 | 65 | 23 | - | None* | Antibiotics / none | N/d | None |

| 17 | M | 1 | Fever | 1 | - | 2 | 47 | 75 | n/d | None* | Antibiotics / none | N/d | None |

| 18§ | F | 18 | Fever of unknown origin | 11 | - | 138 | 31 | 83 | + | CMV, EBV detected in CSF, none*† | Antibiotics / acyclovir added | Normal | Unknown (transfer) |

| 19§ | F | 0.7 | Fever, rash, diarrhea | 5 | + | 9 | 50 | 85 | n/d | None*†, compatible with cow milk allergy | Antibiotics / none | N/d | None |

| 20§ | F | 28 | Fever, headache, vomiting | 1 | - | 136 | 71 | 27 | n/d | Enterovirus in CSF | None / none | N/d | None |

| 21§ | M | 3 | Fever | 1 | - | 6 | 58 | 34 | n/d | Rhinovirus*, diagnosed with pyelonephritis | Antibiotics / none | N/d | None |

| 22§ | F | 4 | Fever, rhinorrhea | 2 | - | 5 | 57 | 78 | n/d | Rhinovirus* | Antibiotics / none | N/d | None |

| 23ठ| M | 1 | Fever, lethargy | 2 | - | 1 | 58 | 73 | n/d | Streptococcus agalactiae sepsis | Antibiotics / ganciclovir | Normal | None |

| 24ठ| M | 2 | Fever, rhinorrhea | 1 | - | 0 | 69 | 45 | n/d | Rhinovirus* | Antibiotics / none | N/d | None |

| 25ठ| M | 44 | Fever, headache, vomiting | 5 | none | 1000 | 45 | 76 | n/d | Enterovirus in CSF | Antibiotics, acyclovir / stop acyclovir | N/d | None |

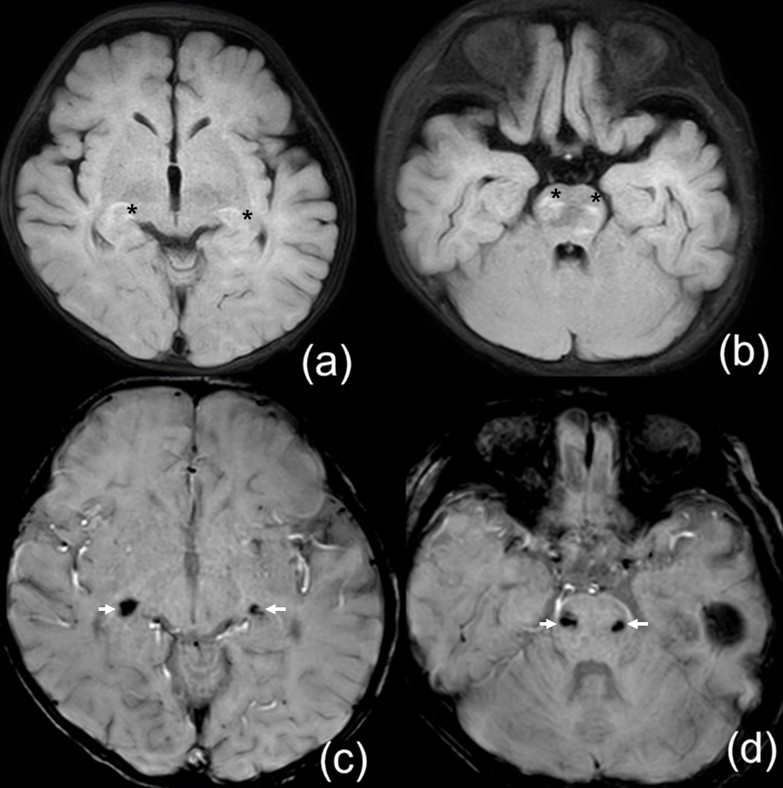

Acyclovir was administered to three patients (Patients 1, 18, 25; 16%). Only Patient 1 was classified as presumed HHV-6 infection, presenting with recurrent seizures and altered consciousness after 3 days of high fever. A rash developed on the fourth day. CSF pleocytosis was observed, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed hyperintensity in the pons, midbrain, and bilateral lower thalami, accompanied by focal hemorrhage (Fig. 1.). Empirical treatment with acyclovir, antibiotics, and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was initiated for suspected encephalitis. HHV-6 infection was confirmed on hospital day 5, when the patient was already improving; therefore, acyclovir was maintained without switching to ganciclovir. The patient recovered without acute sequelae but later developed epilepsy. Patient 25 presented with fever lasting 5 days, headache, lethargy, and CSF pleocytosis, prompting empirical treatment with acyclovir under the impression of encephalitis. Enterovirus and HHV-6 were detected, but treatment was stopped because several features indicated enterovirus infection, including the concurrent seasonal outbreak, marked CSF pleocytosis (>1,000/µL), and rapid clinical improvement within 1–2 days. Patient 18 was admitted with prolonged fever of unknown origin. EBV, CMV, and HHV-6 were detected on multiplex PCR, and acyclovir was started due to suspected EBV infection supported by serology. The patient was transferred before outcome assessment.

Ganciclovir was administered to two patients (4%), both of whom tested positive for HHV-6 using the FA-ME panel on the day of admission. They were treated empirically for lethargy and severe clinical presentation. Patient 10 had an encephalitic course with lethargy and CSF pleocytosis, and no alternative pathogen was identified; the case was therefore considered a presumed HHV-6 infection. The patient recovered fully while receiving ganciclovir and IVIG, and the brain MRI was normal. In contrast, Patient 23 was later diagnosed with group B streptococcal sepsis, and ganciclovir was discontinued.

IVIG was administered to both patients as part of empirical treatment for suspected encephalitis, and they were ultimately considered to have presumed HHV-6 infections (Patients 1 and 10).

Comparison between the infection and bystander groups

Table II shows the comparison of patients classified as presumed HHV-6 infection (n = 17) and presumed bystander (n = 8). Among the patients with presumed infection, Patient 5 had adenovirus detected in respiratory specimens. However, the case was considered presumed HHV-6 infection by consensus, based on the presentation of typical exanthem subitum—several days of high fever followed by rash—and the absence of findings suggestive of adenovirus infection, such as conjunctivitis or respiratory symptoms. Among the patients with bystander detection, Patient 19 developed fever and rash almost simultaneously, accompanied by diarrhea and a positive cow’s milk IgE. These findings were consistent with cow’s milk protein allergy, and the case was therefore considered a bystander.

| Quantitative data are presented as median (interquartile range), qualitative data as number (percentage); ALT, alanine transaminase; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; AST, aspartate transaminase; CIs, confidence intervals; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HHV-6, human herpesvirus 6; *Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, considered statistically significant. | ||||

| Table II. Comparison between the presumed HHV-6 infection group and the presumed bystander group. | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Age, months |

|

|

|

|

| Male |

|

|

|

|

| Fever duration, days |

|

|

|

|

| Rash |

|

|

|

|

| Seizures |

|

|

|

|

| Hospital stay, days |

|

|

|

|

| CSF pleocytosis, n |

|

|

|

|

| CSF WBC, /µL |

|

|

|

|

| CSF glucose, mg/dL |

|

|

|

|

| CSF protein, mg/dL |

|

|

|

|

| Initial ANC, /μL |

|

|

|

|

| Follow-up ANC, /μL |

|

|

|

|

| Initial platelets, x103/μL |

|

|

|

|

| Follow-up platelet, x103/μL |

|

|

|

|

| Follow-up interval, days |

|

|

|

|

| C-reactive protein, mg/L |

|

|

|

|

| AST, U/L |

|

|

|

|

| ALT, U/L |

|

|

|

|

| Treatment with acyclovir |

|

|

|

|

| Treatment with ganciclovir |

|

|

|

|

No significant differences were observed between the two groups in age, sex, fever duration, seizure presentation, length of hospital stay, CSF WBC count, CSF glucose level, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) at admission, CRP level, and antiviral use. In the presumed infection group, rash was more frequent (59% vs. 13%, RD = 46.3% [95% CI: 13.6 – 79.1%], p = 0.04) and CSF protein levels were significantly lower (median 28.0 vs. 74.5 mg/dL, RD = -24.8% [95% CI: -55.6 – 27.4%], p = 0.03). Follow-up studies showed significantly lower ANC (median 1,300 vs. 2,965/μL, RD = -75.3% [95% CI: -89.9% – -39.9%], p = 0.02) and platelet counts (median 186 vs. 322 × 10³/μL, RD = -41.5% [95% CI: -59.0% – -16.5%], p = 0.01) in the presumed infection group, whereas at admission the differences were smaller and only significant for platelet counts. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were higher in the presumed infection group (median 48.0 vs. 29.5 U/L, RD = 74.8% [95% CI: 21.9 – 150.8%], p < 0.01).

Discussion

This study was retrospectively conducted to assess the clinical significance of HHV-6 detected in the CSF of pediatric patients over a 10-year period. Of the 25 HHV-6–positive-cases, 17 were classified as presumed HHV-6 infection, which is commonly associated with rash and cytopenia. The findings of this study may provide insights into markers of pathogenic HHV-6 infection and assist clinicians in interpreting CSF HHV-6 results in pediatric settings.

In our cohort, HHV-6 was detected in 1.3% (25/1,865) of children who were tested, with a median age of 6 months; nearly half of the patients were <6 months, slightly below the usual peak of 6–9 months.4 This younger distribution likely reflects the frequent lumbar punctures for unexplained fever rather than clinical suspicion of exanthem subitum. A similar pattern was described by Pandey et al.,12 who found HHV-6 in 2.5% of 1,005 children, with a median age of 0.55 years. Detection at such an early age may raise concerns about immune immaturity; nonetheless, antiviral therapy was rarely required. In our series, only one infant received ganciclovir before group B streptococcus sepsis was confirmed, while in the Pandey et al.12 study, none were treated; nevertheless, all infants aged < 6 months recovered without complications. These findings suggest that, in otherwise healthy infants, HHV-6 detection alone should be interpreted with caution before initiating antiviral therapy. Pandey et al.12 exclusively used the FA-ME panel, which is reported to have a lower sensitivity for HHV-6 than the conventional PCR used in most of our cases. Therefore, the higher detection rate in their study likely reflects population differences rather than assay performance. Studies focusing on specific clinical groups have shown even higher detection rates of approximately 6% in febrile seizure cases13 and up to 33% in meningoencephalitis cases.9

All 25 HHV-6–positive patients in our cohort presented with fever; seizures occurred in seven (28%) and ataxia in one (4%). Antivirals were administered in five cases—three received acyclovir and two ganciclovir—with one patient in each group also given IVIG. These two (Patients 1 and 10) were ultimately classified as HHV-6 meningoencephalitis. While limbic involvement is typical in HHV-6 encephalitis, thalamic and brainstem lesions are also frequent in children and consistent with this case.14 Focal hemorrhages, though rarely described, have been reported in fatal cases.15 In contrast, our patient recovered without acute sequelae, though epilepsy later developed. The patient was treated with acyclovir and IVIG. However, because acyclovir has limited activity against HHV-6,16 the favorable outcome was likely driven more by the addition of IVIG than by antiviral therapy itself. Patient 10, who presented with symptoms of encephalitis and a normal MRI result, also received ganciclovir plus IVIG soon after admission and recovered fully. Because both patients with encephalitis received combination therapy, the specific contribution of each component could not be determined. However, the favorable outcomes in our study contrast with those in a nationwide Japanese report, where nearly half of 60 pediatric patients developed long-term sequelae despite treatment.17 In that cohort, 51.7% received antivirals, 55.0% steroids, and 31.7% immunoglobulins, but outcomes were not analyzed by treatment regimen.17 By contrast, in a Korean series, better results were reported in patients treated with both antivirals and IVIG than in those who received antivirals alone,18 consistent with our observations. Taken together, these findings suggest that early combination therapy, particularly including IVIG, may improve outcomes in HHV-6 encephalitis, although current evidence remains limited. Larger studies are needed to establish optimal treatment strategies. Notably, both patients in our study who received ganciclovir were diagnosed early using the FA-ME panel. While one case aligned with presumed HHV-6 encephalitis, the other was ultimately diagnosed as group B streptococcus sepsis. This contrast underscores the risk of overtreatment based on early detection alone and highlights the need to interpret HHV-6 results within the full clinical context.

Differentiating clinically significant HHV-6 infection from incidental detection remains a key challenge in interpreting CSF PCR results. In our cohort, 17 of 25 HHV-6–positive cases were classified as presumed infection, while 8 were considered bystander detections when another pathogen or a more plausible diagnosis was present. Among distinguishing features, rash was significantly more frequent in the presumed infection group (59% vs. 13%, p = 0.04)—an unexpected finding given that roseola-like rashes were part of the case definition. Ward et al.11 similarly reported rash in 67% of confirmed primary infection cases but only 10% of ciHHV-6 cases, supporting its potential role as a clinical marker. The groups were also distinguished by the hematologic findings. At admission, ANC tended to be lower in the presumed infection group than in the bystander group; however, the difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, platelet counts were already significantly lower in the presumed infection group at admission. On follow-up, both ANC and platelet counts showed clearer differences in the presumed infection group. AST levels were also higher in this group. These results are consistent with those of prior studies suggesting HHV-6–associated bone marrow suppression.19,20 Miura et al.19 observed severe neutropenia in 30% of primary HHV-6 cases, particularly between days 5 and 10, often with thrombocytopenia, AST elevation, and chemokine increases, suggesting an inflammation-mediated contribution to myelosuppression. Consistent with this finding, our cohort showed progressive declines in ANC and platelet counts. AST levels were elevated at admission in the presumed infection group, but without follow-up data this finding should be interpreted cautiously, as seizures—more frequent in this group—may also have contributed. In contrast, CSF pleocytosis did not differ between groups and was not useful for assessing clinical relevance, consistent with reports that pleocytosis is often absent even in HHV-6 CNS infections.5,12 Finally, higher CSF protein in the presumed bystander group (74.5 vs 28.0 mg/dL; p = 0.03) may reflect age-related physiology (4 vs 7 months); hence we did not rely on this finding to distinguish the groups. This interpretation is supported by our effect size analysis, in which the CI for the RD included zero (RD = -24.8% [95% CI: -55.6% to 27.4%], indicating that the difference was not statistically robust.

This study has several limitations. First, as this was a retrospective study, some clinical details were incomplete. The immune status of patients is a key factor in interpreting the clinical relevance of HHV-6 detection. However, detailed data on immune function were not consistently available because of the retrospective design of the study. Second, the number of patients, especially those with HHV-6 encephalitis, was small, limiting generalizability and precluding robust statistical comparisons. Notably, the non-significant differences between the two groups were underpowered, with post-hoc power analysis showing values ranging from 0.03 to 0.49. Third, classification into presumed infection and bystander groups was based on clinical judgment rather than virological confirmation, and this approach may be debated. However, such clinical categorization is not unique to our study. Wang et al.21 used a similar clinical classification and found strong concordance between clinical and virological definitions, noting that fever was the most reliable clinical feature distinguishing primary infection from bystander detection. Consistent with our findings, Pandey et al.12 reported that approximately half of HHV-6–positive cases occurred in infants aged < 6 months, most of them presenting with fever. They also confirmed ciHHV-6 in only a minority of tested patients, all of whom were infected with another plausible pathogen.12 These parallels suggest that, while not definitive, our classification appears clinically reasonable. Finally, we lacked confirmatory assays (viral load, serology, or ciHHV-6 testing) and long-term follow-up, limiting confirmation of active infection and assessment of late neurological outcomes. Prospective studies with standardized virological testing and longitudinal follow-up are needed to refine classification and clarify the clinical significance of HHV-6 detected in pediatric CSF.

In conclusion, HHV-6 detection in CSF may not always indicate active infection. Encephalitis was rare in our cohort, and although affected patients recovered without acute sequelae, the findings should be interpreted with caution because of the small sample size and limited follow-up. Clinical features, such as rash, together with laboratory changes like cytopenia and elevated AST, may help assess clinical relevance. Careful interpretation is especially important in young children, particularly when considering antiviral treatments.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gyeongsang National University Hospital, with a waiver of informed consent due to its retrospective design (IRB No. GNUH-2025-05-20).

Source of funding

This work was supported by the New Faculty Research Support Grant from Gyeongsang National University in 2025 (grant no: GNU-NFRSG-0054).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Dockrell DH. Human herpesvirus 6: molecular biology and clinical features. J Med Microbiol 2003; 52: 5-18. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.05074-0

- Karimi A, Sakhavi M, Nahanmoghaddam N, et al. Evaluation of viral (HHV6, adenovirus, HSV1, enterovirus) and bacterial infection in children with febrile convulsion by serum PCR and blood culture mofid children’s hospital 2016-2017. Arch of Pediatr Infect Dis 2018; 6: e63954. https://doi.org/10.5812/pedinfect.63954

- Inoue J, Weber D, Fernandes JF, et al. HHV-6 infections in hospitalized young children of Gabon. Infection 2023; 51: 1759-1765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-023-02077-w

- Hall CB, Long CE, Schnabel KC, et al. Human herpesvirus-6 infection in children: a prospective study of complications and reactivation. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 432-438. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199408183310703

- Nikolskiy MA, Lioznov DA, Gorelik EU, Vishnevskaya TV. HHV-6 in cerebrospinal fluid in immunocompetent children. BioMed 2023; 3: 420-430. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed3030034

- Okada K, Ueda K, Kusuhara K, et al. Exanthema subitum and human herpesvirus 6 infection: clinical observations in fifty-seven cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1993; 12: 204-208. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199303000-00006

- Yamamoto S, Takahashi S, Tanaka R, et al. Human herpesvirus-6 infection-associated acute encephalopathy without skin rash. Brain Dev 2015; 37: 829-832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2014.12.005

- Mostyn A, Lenihan M, O’Sullivan D, et al. Assessment of the FilmArray® multiplex PCR system and associated meningitis/encephalitis panel in the diagnostic service of a tertiary hospital. Infect Prev Pract 2020; 2: 100042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infpip.2020.100042

- Abdelrahim NA, Mohamed N, Evander M, Ahlm C, Fadl-Elmula IM. Human herpes virus type-6 is associated with central nervous system infections in children in Sudan. Afr J Lab Med 2022; 11: 1718. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajlm.v11i1.1718

- Daibata M, Taguchi T, Nemoto Y, Taguchi H, Miyoshi I. Inheritance of chromosomally integrated human herpesvirus 6 DNA. Blood 1999; 94: 1545-1549.

- Ward KN, Leong HN, Thiruchelvam AD, Atkinson CE, Clark DA. Human herpesvirus 6 DNA levels in cerebrospinal fluid due to primary infection differ from those due to chromosomal viral integration and have implications for diagnosis of encephalitis. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45: 1298-1304. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02115-06

- Pandey U, Greninger AL, Levin GR, Jerome KR, Anand VC, Dien Bard J. Pathogen or bystander: clinical significance of detecting human herpesvirus 6 in pediatric cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 58: e00313-e00320. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00313-20

- Mamishi S, Kamrani L, Mohammadpour M, Yavarian J. Prevalence of HHV-6 in cerebrospinal fluid of children younger than 2 years of age with febrile convulsion. Iran J Microbiol 2014; 6: 87-90.

- Crawford JR, Chang T, Lavenstein BL, Mariani B. Acute and chronic magnetic resonance imaging of human herpesvirus-6 associated encephalitis. J Pediatr Neurol 2009; 7: 367-373. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPN-2009-0331

- Ahtiluoto S, Mannonen L, Paetau A, et al. In situ hybridization detection of human herpesvirus 6 in brain tissue from fatal encephalitis. Pediatrics 2000; 105: 431-433. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.105.2.431

- Amjad M, Gillespie MA, Carlson RM, Karim MR. Flow cytometric evaluation of antiviral agents against human herpesvirus 6. Microbiol Immunol 2001; 45: 233-240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1348-0421.2001.tb02612.x

- Yoshikawa T, Ohashi M, Miyake F, et al. Exanthem subitum-associated encephalitis: nationwide survey in Japan. Pediatr Neurol 2009; 41: 353-358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.05.012

- You SJ. Human Herpesvirus-6 may be neurologically injurious in some immunocompetent children. J Child Neurol 2020; 35: 132-136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073819879284

- Miura H, Kawamura Y, Ozeki E, Ihira M, Ohashi M, Yoshikawa T. Pathogenesis of severe neutropenia in patients with primary human herpesvirus 6B infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015; 34: 1003-1007. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000000777

- Hashimoto H, Maruyama H, Fujimoto K, Sakakura T, Seishu S, Okuda N. Hematologic findings associated with thrombocytopenia during the acute phase of exanthem subitum confirmed by primary human herpesvirus-6 infection. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2002; 24: 211-214. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043426-200203000-00010

- Wang H, Tomatis-Souverbielle C, Everhart K, Oyeniran SJ, Leber AL. Detection of human herpesvirus 6 in pediatric CSF samples: causing disease or incidental distraction? Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2023; 107: 116029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2023.116029

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.