Graphical Abstract

Abstract

Background. Urinary tract infection (UTI) is a significant issue in childhood due to its high prevalence and potential long-term complications. Several studies have suggested that vitamin D deficiency is an influential factor in the progression of infection. This study aims to determine the value of serum vitamin D levels in predicting renal scarring among children with febrile UTIs.

Methods. This study was conducted through a census sampling method from September 2019 to November 2021, with a 6-month follow-up period to survey children with their first febrile UTI who were referred to the nephrology clinic of a tertiary academic hospital. Out of 193 referred children, 55 met the inclusion criteria. Patients were excluded if they had a previous history of UTI, recurrent or breakthrough infection, delay in treatment initiation, hospitalization, ultrasonographic abnormality, hypertension, neurogenic bladder, or renal failure. Five additional cases were excluded due to incomplete follow-up. The study was completed with 50 participants, aged between 3 and 98 months.

The main outcomes were measuring serum vitamin D levels during the acute phase of UTIs and conducting dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scans four to six months later. Logistic regression was used to determine the correlation between vitamin D levels and DMSA findings.

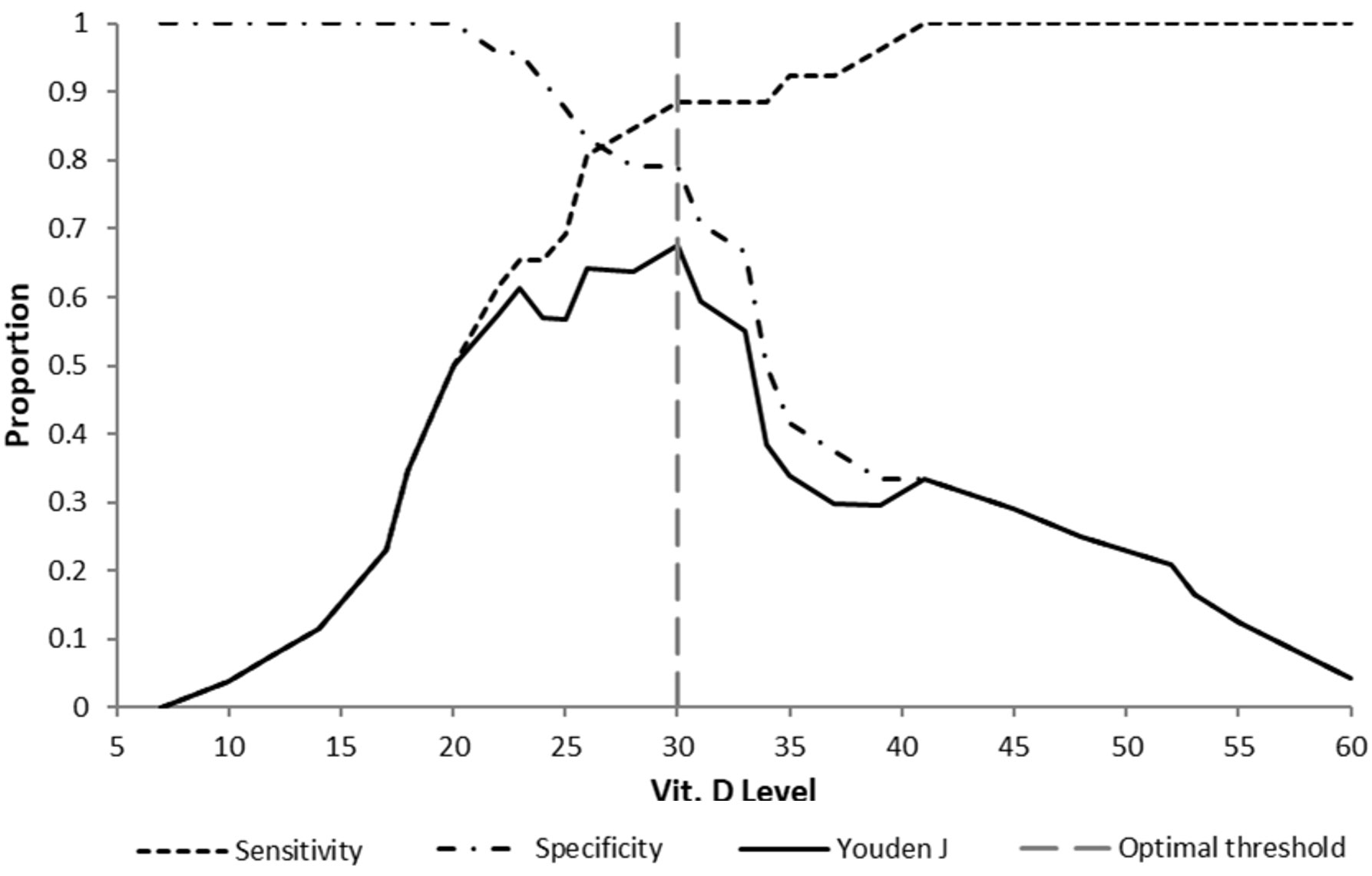

Results. Levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D were significantly associated with renal scarring (p = 0.0001); mean serum concentrations were significantly lower in patients with renal scarring (20.7 ± 7.8 ng/mL) than in those without renal scarring (37.1 ± 11.4 ng/mL). A serum vitamin D concentration of less than 30 ng/mL was determined as the best predictor of post-UTI renal scarring (positive LR 4.25, Youden’s j index 0.676).

Conclusions. The study showed a negative correlation between renal scarring and serum vitamin D levels. It has been found that serum vitamin D level is a good predictor of renal scarring.

Keywords: dietary supplements, immune system, pyelonephritis

Introduction

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common problem in childhood that can lead to kidney damage and renal scarring. Hypertension, albuminuria, and chronic kidney disease are serious consequences of long-term kidney damage and renal scarring.1,2 Several factors may affect UTI outcomes and lead to renal scarring. The severity and frequency of UTIs play a role, with more severe or recurrent infections increasing the likelihood of scar formation.1,3 Recent studies have attempted to determine whether antioxidants, micronutrients, or vitamins have a preventive effect against UTI scars and complications.4-8

Understanding the correlation between vitamin D levels and renal scarring in children with UTIs is an area of ongoing research. Vitamin D has well-known functions in bone and calcium metabolism, but newer findings show its immunomodulatory role and effect on defense mechanisms against infections.9,10 Although high-dose vitamin D supplementation is generally well tolerated in children, vitamin D deficiency is common and has been associated with increased production of inflammatory cytokines, which might exacerbate tissue damage and renal scarring.11,12 The ability of the immune system to kill pathogens may be compromised by vitamin D deficiency, leading to more severe and recurrent UTIs and ultimately resulting in renal scarring.10,12,13 This prognostic study investigates whether serum vitamin D levels can predict the development of renal scars in children with febrile UTIs.

Methods

Study design

In this diagnostic / prognostic study, a complete enumeration survey method (census sampling) was used to evaluate 193 patients aged between one month and 11 years with urinary problems and the possibility of UTI referred to the nephrology clinic of our academic hospital from September 2019 until November 2021.

Participants’ demographic information, such as age and gender, was collected and recorded from self-identified patients. Patient height and weight were recorded. Height-for-age and weight-for-age standard deviation scores (SDS) and malnutrition status were calculated using World Health Organization (WHO) growth standards. Malnutrition status was defined according to the WHO weight-for-age SDS criteria. For children from birth to 60 months, the WHO Child Growth Standards were applied using Anthro Survey Analyzer. AnthroPlus software was used for individuals from 61 months to 19 years to apply the WHO Reference 2007.14 Clinical and laboratory findings were used to confirm acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis for enrollment in the study. Laboratory examinations consisted of urinalysis and urine culture, white blood cell count, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels, serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), alkaline phosphatase, phosphorus, calcium, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels which were obtained immediately after suspicion of clinical UTI. Urine samples for urinalysis and culture were obtained via mid-stream clean catch sampling in all continent and cooperative patients. Otherwise, catheterization with a catheter of the appropriate size was used in small children or incontinent individuals. All creatinine measurements were performed using the Jaffe method. Normal renal function for patients aged over 2 years was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) greater than 90 mL/min/1.73m², calculated using the Schwartz formula.15 For children ≤ 24 months old, GFR within 1 standard deviation below the mean for age was considered normal.16 The total serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D as an index test was measured in venous blood samples using a combination of enzyme immunoassay competition method with final fluorescent detection - enzyme linked fluorescent assay - (ELFA) by the VIDAS® 25 OH Vitamin D TOTAL kit, and was expressed as nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL).17

Ultrasonographic examinations were performed for all children during the first week after diagnosis. All enrolled patients received cefixime 8 mg/kg per day orally divided every 12 hours, followed by a week of oral antibiotics based on the antibiogram results. The efficacy of treatment was confirmed by a negative urine culture 3 days after discontinuation of antibiotic therapy. Monthly urine tests and urine cultures were conducted for four to six months in all patients to ensure no recurrence of infection. A Tc-99m 2,3-DMSA scan, the current gold standard for detecting renal scarring, was performed four to six months after the onset of pyelonephritis to assess kidney involvement.18 Any DMSA scan report indicating differential renal function (DFR) out of the range of 50%±5% and/or showing the existence of scarring in the kidney, regardless of the number, severity, unilateral or bilateral involvement, was considered a subject with scarring complications.

The study followed the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) 2015 reporting guideline.19

Exclusion and inclusion criteria

According to the clinical and laboratory criteria, the conditions for entering the study as pyelonephritis were as follows: The clinical criteria consisted of eight signs, including fever, hypothermia, shivering, abdominal or costovertebral pain, weakness, nausea, and vomiting. At least three out of eight clinical criteria, together with any of the following urinary symptoms such as irritability during urination, frequency, painful urination, malodor urine, the reappearance of bedwetting, cloudy or darker urine as well as frank hematuria were considered for the clinical diagnosis of pyelonephritis.20 The laboratory criterion was a positive urine culture (a midstream urine sample with more than 105 colony forming units (CFU)/mL, a catheterized urine culture of more than 50,000 cfu/mL or a suprapubic urine sample with more than 100 colonies of one type of organism) plus at least two of three of the following laboratory findings: first-hour ESR > 15 mm/hr, CRP > 5 mg/dL, and WBC > 10,000 per microliter. For children aged 2 to 24 months presenting with fever or hypothermia, a UTI was defined by a urinalysis indicative of infection (either pyuria of >10 white blood cells per high-power field or bacteriuria) in conjunction with a positive urine culture.21

Patients were excluded from the study if they did not have urinary symptoms, were hospitalized, or had a delay in initiation of treatment of more than 5 days from the onset of clinical signs or symptoms. Patients were also excluded if they experienced breathing problems, abnormal chest sounds, abnormal ear exam, fever with known alternative cause, had any positive history of UTIs, hypertension, known cases of obstructive urinary system disease, myelomeningocele, paraplegia, urinary stones, and immunodeficiency conditions. Patients who received immunosuppressive medications or vitamin D supplementation in the last month before UTI onset and those with abnormal eGFR were also excluded.

Children with ultrasonographic results such as trabeculated bladder wall, increased renal parenchymal echogenicity, irregular kidney borders, or with a solitary or ectopic kidney, as well as those with anatomical findings such as duplicated system, horseshoe kidney, renal cyst, mass or abscess; or with pelvicalyceal dilation (maximal anteroposterior mid pelvic diameter ≥4 mm) with or without ureteral dilatation, were excluded. Children were excluded based on a significant renal length discrepancy. For those under four years of age, a discrepancy was defined as a right kidney ≥6 mm longer than the left, or a left kidney ≥10 mm longer than the right. For older children, the threshold for exclusion was a discrepancy of ≥10 mm, regardless of which kidney was larger.22

Patient categorization and statistical analysis

Differential renal function below 45% and/or a defined scar by DMSA scan was considered abnormal. Based on DMSA findings, groups with normal (no-scar) and abnormal (scar+) DMSA findings were assigned for statistical analysis. The Shapiro‒Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the data distribution. Student’s t-test was used for normal data and the Mann-Whitney test for non-normal data distribution. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to determine the serum vitamin D concentration that best predicted an abnormality by DMSA scan.23 The positive likelihood ratio, Youden’s J index, and decision threshold were used to compare various levels of serum vitamin D to determine the best cutoff for serum vitamin D concentrations for predicting the likelihood of post-pyelonephritis renal scar occurrence.24 Serum Vitamin D levels below the cut-off were considered positive index tests. Similarly, levels equal to/or above the cut-off were defined as negative index tests. By definition, the sensitivity was the proportion of those with abnormal DMSA scans who had positive index tests and the specificity was the proportion of those with normal DMSA scans who had negative index tests. The positive predictive value (PPV) was the proportion of those with positive index test results who had an abnormal DMSA scan. The negative predictive value (NPV) was the proportion of individuals with negative index test results who had a normal DMSA scan.25 A p value of less than 5% was considered significant. Logistic regression was used in multivariate analysis. Prior to multivariate modeling, univariate screening was performed to reduce overfitting risk. Variables associated with the outcome at p < 0.1 were retained to enhance model stability. The SPSS statistical software v.21.3 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and Analyse-it® 5.80.2 were used for statistical analysis.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research.26 Before implementing the plan, we obtained informed consent from the parents of all individuals included in the study. Notably, no additional costs were imposed on the patients.

Results

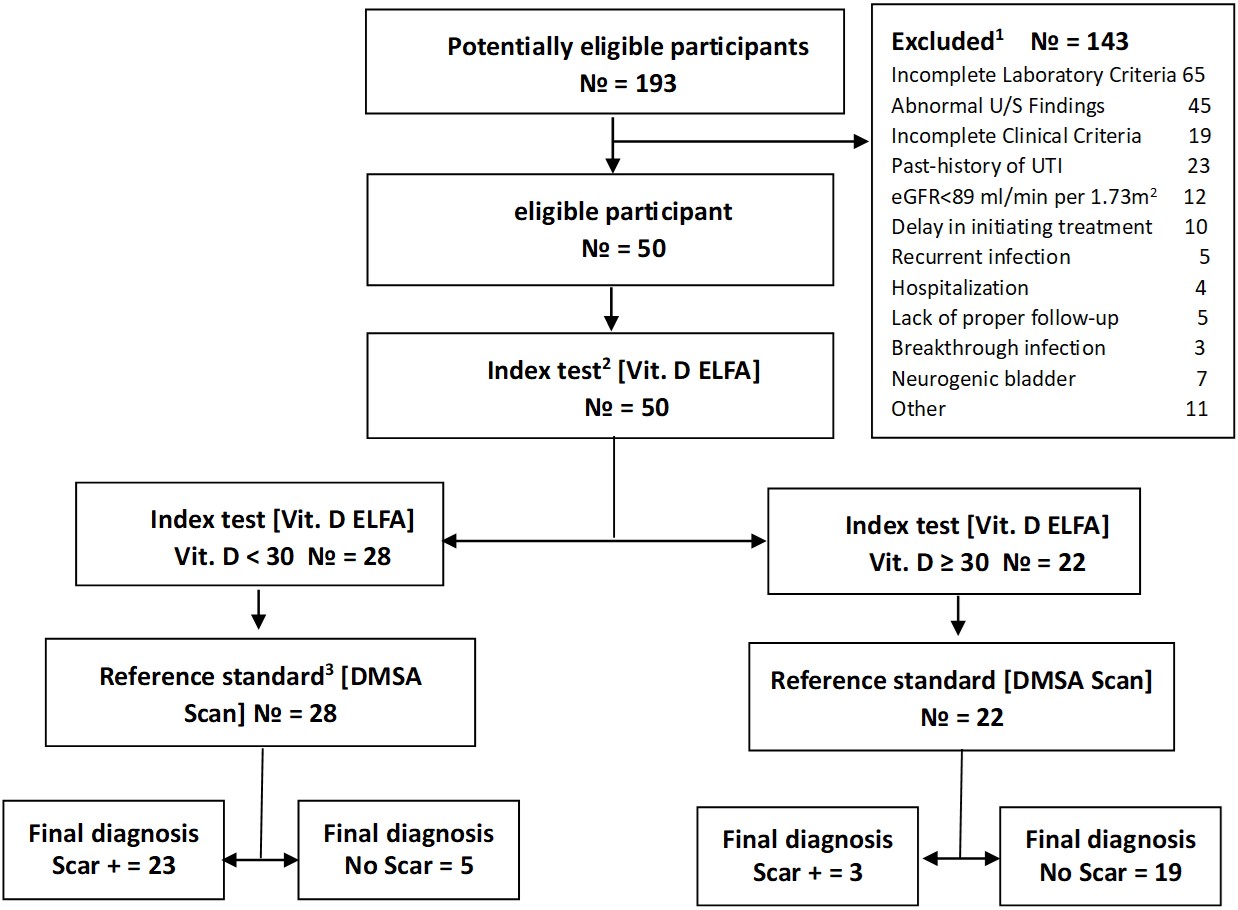

From the initial 193 referred children, 143 patients were excluded for reasons mentioned in Fig. 1. Of these, 106 had one excluded factor, 18 had two, eleven had three, six had four, and two had five involved factors. Fifty outpatients with a normal glomerular filtration rate, aged 3 to 98 months, with pyelonephritis were enrolled in the study; 28% (14 patients) were boys, and 72% were girls. The demographic and anthropometric characteristics of enrolled patients are presented in Table I. Kidney scars were revealed by DMSA scan in 26 people (52%), 17 girls (65%) and 9 boys (35%).

2Index test: Serum vitamin D level measured by Enzyme-Linked Fluorescent Assay (ELFA) at the onset of UTI.

3Reference standard: Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scan examination done 4 to 6 months later.

|

SDS: standard deviation score, * Distribution of population is not normal at the 5% significance level |

||||

| Table I. Demographic characteristics and laboratory data of the enrolled patients | ||||

| Characteristic |

|

|

|

|

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|||

| Male |

|

|

|

|

| Female |

|

|

|

|

| Age (months), mean ± SD |

|

|

|

|

| Anthropometrics, mean ± SD | ||||

| Height (cm) |

|

|

|

|

| Height-SDS |

|

|

|

|

| Weight (kg) |

|

|

|

|

| Weight-SDS |

|

|

|

|

| Malnutrition Status, n (%) | ||||

| Overweight (SDS ≥ 2) |

|

|

|

|

| Normal (SDS ≥ -2 to 2) |

|

|

|

|

| Moderate underweight (SDS ≥ -2 to -3) |

|

|

|

|

| Severe underweight (SDS < -3) |

|

|

|

|

Urine culture results showed Escherichia coli in 36 patients (72%). Non-E. coli cultures consisted of Enterobacter (5), Klebsiella (4), Pseudomonas (2), Citrobacter (1), Staphylococcus epidermidis (1), and Staphylococcus aureus (1). Renal scars occurred in 55.5% and 42.8% of E. coli vs non-E. coli patients, respectively.

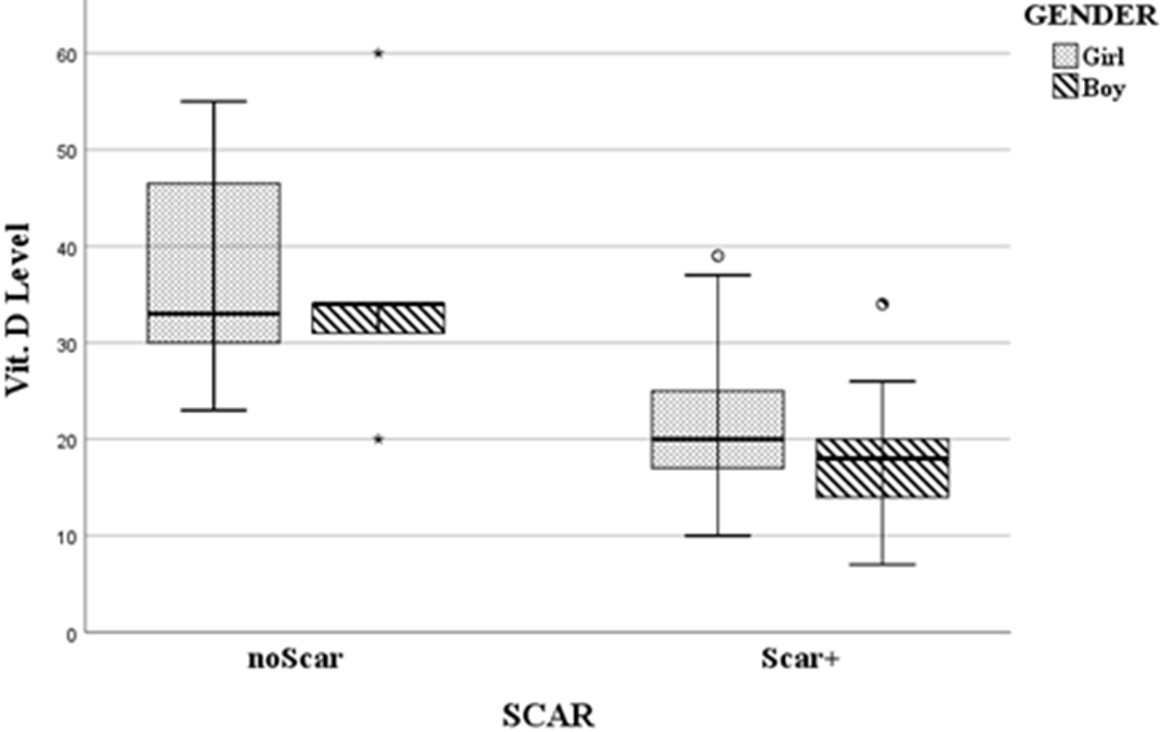

The mean vitamin D levels of patients were 28.58 ± 12.65 (7-60) ng/dL. There was no significant effect of gender regarding the average level of serum vitamin D; 30.1 ± 12.3ng/mL for girls and 24.8 ± 13.3 ng/mL for boys, respectively, t(48)= -1.33, p=0.19. Table I presents additional relevant information about ESR and CRP values, including mean ± standard deviation and median values in patients.

Correlation between the serum and urine parameters and renal scarring status

The study compared the average vitamin D, ESR, and CRP values in scar and non-scar groups among girls, boys, and all patients.

The lowest and highest vitamin D levels were 7 and 39 ng/mL in the scar group, and 20 and 60 ng/mL in the non-scar group, respectively. There was a significant difference in vitamin D serum levels between the two groups (p < 0.0001). This difference was observed when the groups were subdivided by gender (Table II, Fig. 2). The comparison of average levels of CRP and ESR in both the scar and non-scar groups and their subdivided groups showed no significant differences, as presented in Table II.

| 25(OH)D: 25-hydroxyvitamin D, CI: confidence interval, CRP: C-reactive protein, ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate, SD: standard deviation. | |||||||

| Table II. Serum levels of Vitamin D, CRP, and ESR with and without renal scarring in children with febrile urinary tract infections, categorized by sex | |||||||

| Variable |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | |||||||

| Females |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Males |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ESR (mm/hr) | |||||||

| Females |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Males |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CRP (mg/dL) | |||||||

| Females |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Males |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The impact of various factors on renal scarring was examined via logistic regression analysis. The variables of age, sex, height-SDS, vitamin D concentration, ESR, CRP levels, and type of urine culture (i.e., E. coli vs. non-E. coli) were considered. To mitigate overfitting and ensure model stability, univariate screening identified three variables (p < 0.1) for retention in the multivariate analysis: age, vitamin D concentration, and CRP. By controlling the effect of confounding variables, vitamin D level at the initial presentation of acute UTI has a significant relationship with renal scarring (β = -.135, p < .003), as detailed in Supplementary Table S1.

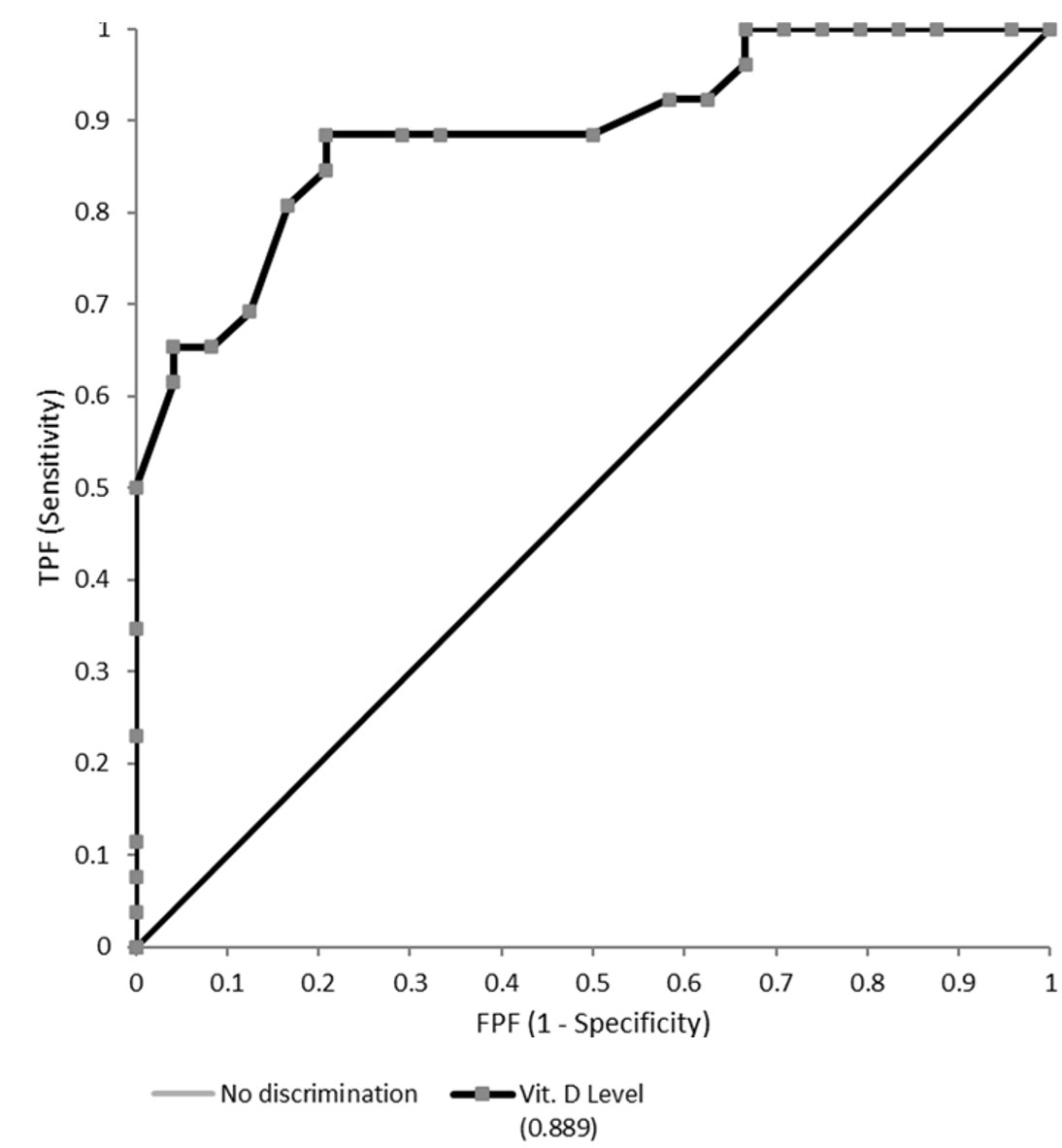

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis

The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.89 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.798 - 0.979; Fig. 3). Reporting on the increase in discrimination using the ROC curve and AUC ≥ 0.8 is relevant to obtaining insight into the incremental value of serum vitamin D levels and defining the prediction model.23 Therefore, we can reject the null hypothesis that serum vitamin D level cannot predict the occurrence of renal scarring. However, defining a decision threshold or cut-off i.e. going from a prediction model to a prediction rule, is crucial to using the prediction test for decision-making in clinical practice.27,28 The optimal threshold value or cutoff point for the serum vitamin D concentration was determined to be 30 ng/mL as shown in the decision threshold curve (Youden’s J index = 0.676, t* = 30; Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S2). At this point, the estimated specificity and sensitivity are 0.792 and 0.885, respectively.

Discussion

Childhood UTIs may lead to kidney scar formation and complications such as hypertension and renal failure.1,2 Major risk factors for renal scarring include recurrent infections, delayed treatment, young age, and immune deficiency.3 While vitamin D deficiency has been proposed as a risk factor, studies investigating the correlation between vitamin D intake and UTIs in children have yielded different outcomes.12 Our research findings suggest that a higher serum vitamin D level at UTI onset is correlated with a reduced risk of renal scarring after the first pyelonephritic attack. Although we could not find any similar research, vitamin D deficiency was found to be an independent risk factor in patients with recurrent UTIs according to Sürmeli Döven’s study.12 Most studies have focused on the correlation between vitamin D levels and the occurrence of UTIs. Sherkatolabbasieh et al. reported no significant correlation between vitamin D levels and UTIs, whereas other researchers have shown a significant negative correlation, with lower vitamin D levels associated with a greater risk of childhood UTIs.29-31

Vitamin D, a fat-soluble vitamin, plays an important role in regulating bone metabolism and cell growth, and is critical for the optimal immune system.32 Vitamin D is known as an immune response modulator and regulates innate immunity through macrophage and dendritic cell activity, as well as through an adaptive immune response via lymphocyte T cells.10 Several observational studies have shown that vitamin D influences innate immunity through the upregulation of antimicrobial peptides, such as the CAMP/LL37 peptide, which has antibacterial properties.9 Therefore, poor vitamin D status is associated with greater susceptibility to infections.

Strong laboratory and epidemiological evidence links vitamin D deficiency to increased rates of UTIs.31,33-35 Adequate vitamin D levels can decrease pro-inflammatory cytokine levels released predominantly from innate immune cells.36 Pro-inflammatory cytokine production is crucial for initiating the anti-infectious process, but their exacerbated production during severe inflammation may contribute to serious consequences. The capacity of interleukin (IL)-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) to induce inflammatory mediator expression contributes to their pro-inflammatory properties.37 IL-1 and TNF-a activate phospholipase, cyclooxygenase, and lipoxygenase leading to the release of prostaglandins, thromboxane, leukotrienes, and platelet-activating factor (PAF). Free radicals (superoxide [O2−], nitric oxide [NO]), and proteolytic enzymes are other mediators produced by target cells in response to IL-1 and TNF-a. Other cytokines, including chemokines such as IL-8 and some T-cell-derived cytokines, such as lymphotoxin-α, are also involved in the cytokine cascade.37 Insufficient vitamin D can induce an inflammatory cascade that leads to severe inflammation and additional organ damage.12

Vitamin D stimulates the synthesis of antimicrobial peptides, cathelicidins, and defensins, which exhibit broad-spectrum activity against viruses, bacteria, and fungal infections; reduce the concentration of proinflammatory cytokines; and increase the concentration of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Vitamin D is also involved in the differentiation, maturation, and proliferation of immune cells.10 Mohanty et al found tight junction proteins such as occludin and claudin-14 induced by vitamin D during E. coli infection restores the bladder epithelial integrity and can prevent bacterial invasion through the epithelial barrier.38

The WHO recommends maintaining a serum vitamin D concentration above 20 ng/ml.39 However, the National Institute of Health suggests that for certain at-risk groups, such as elderly individuals, pregnant women, and those with chronic conditions, a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level above 30 ng/mL is necessary.40 This is supported by Vieth who argues that the current tolerable upper intake level of vitamin D may be too low and that higher serum levels may be more beneficial than harmful.41

In our study, the ROC curve analysis showed an AUC of 0.89, indicating that it is a reliable measurement to predict renal scarring on the DMSA scan.23 The optimal prognostic threshold for serum vitamin D concentration was identified as 30 ng/mL, exceeding the WHO’s sufficiency guideline of 20 ng/ml.39

These findings suggest that monitoring serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels may be important in assessing the risk of renal scarring in children with febrile UTIs. Vitamin D levels are influenced by ethnicity, genetic factors, and skin pigmentation, with higher melanin concentrations requiring greater sunlight exposure for adequate synthesis.42-44 Therefore, future studies should include diverse geographic and racial/ethnic populations to enhance the generalizability of findings.

We need to acknowledge that our study has some limitations and points. First, radionuclide scans were intentionally deferred during the acute infection phase to minimize radiation exposure in pediatric patients. Instead, we relied solely on their medical history and ultrasound imaging to detect any evidence of renal scarring. Thus, previous non-obvious UTIs and related scarring or renal abnormalities from other issues could impact the selection bias in our study. Next, we attempted to eliminate all known confounding factors to assess the effect of vitamin D deficiency alone. Despite the exclusion of many patients, the net effect of vitamin D deficiency on renal scarring in pyelonephritis was ultimately analyzed. We suggest prospective studies could consider integrating early-phase imaging to better distinguish pre-existing damage from new-onset scarring.

Conclusion

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between vitamin D levels and post-UTI renal scarring in children. A reverse correlation was found between post-pyelonephritis renal scarring and serum vitamin D levels. Moreover, the results indicated that only vitamin D levels were significantly related to renal scarring. The ROC curve analysis demonstrated that serum vitamin D levels exhibit an acceptable AUC, suggesting its potential utility as a prognostic marker for renal scarring. Serum vitamin D ≥ 30 ng/mL demonstrated prognostic value for renal scarring outcomes in pediatric pyelonephritis, warranting consideration as a risk-stratification biomarker in susceptible populations.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Mojtaba Meshkat, Ph.D. in Biostatistics, contributed by critically reviewing statistical analysis. There was no financial compensation for this contribution.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad Medical Sciences of Islamic Azad University (registered by The Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran; date: May 2019, number: IR.IAU.MSHD.REC.1398.033).

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Tullus K. Outcome of post-infectious renal scarring. Pediatr Nephrol 2015; 30: 1375-1377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-015-3130-6

- Baltu D, Salancı BV, Gülhan B, Özaltın F, Düzova A, Topaloğlu R. Albuminuria is associated with 24-hour and night-time diastolic blood pressure in urinary tract infection with renal scarring. Turk J Pediatr 2023; 65: 620-629. https://doi.org/10.24953/turkjped.2022.766

- Shaikh N, Haralam MA, Kurs-Lasky M, Hoberman A. Association of renal scarring with number of febrile urinary tract infections in children. JAMA Pediatr 2019; 173: 949-952. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2504

- Allameh Z, Salamzadeh J. Use of antioxidants in urinary tract infection. J Res Pharm Pract 2016; 5: 79-85. https://doi.org/10.4103/2279-042X.179567

- Kahbazi M, Sharafkhah M, Yousefichaijan P, et al. Vitamin A supplementation is effective for improving the clinical symptoms of urinary tract infections and reducing renal scarring in girls with acute pyelonephritis: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled, clinical trial study. Complement Ther Med 2019; 42: 429-437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2018.12.007

- Jorde R, Sollid ST, Svartberg J, Joakimsen RM, Grimnes G, Hutchinson MYS. Prevention of urinary tract infections with vitamin D supplementation 20,000 IU per week for five years. Results from an RCT including 511 subjects. Infect Dis (Lond) 2016; 48: 823-828. https://doi.org/10.1080/23744235.2016.1201853

- Sedighi I, Taheri-Moghadam G, Emad-Momtaz H, et al. Protective effects of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation against renal parenchymal scarring in children with acute pyelonephritis: results of a pilot clinical trial. Curr Pediatr Rev 2022; 18: 72-81. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573396317666210909153643

- Khan DSA, Naseem R, Salam RA, Lassi ZS, Das JK, Bhutta ZA. Interventions for high-burden infectious diseases in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2022; 149: e2021053852C. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-053852C

- Ismailova A, White JH. Vitamin D, infections and immunity. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2022; 23: 265-277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-021-09679-5

- Baeke F, Takiishi T, Korf H, Gysemans C, Mathieu C. Vitamin D: modulator of the immune system. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2010; 10: 482-496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2010.04.001

- Brustad N, Yousef S, Stokholm J, Bønnelykke K, Bisgaard H, Chawes BL. Safety of high-dose vitamin D supplementation among children aged 0 to 6 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2022; 5: e227410. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.7410

- Sürmeli Döven S, Erdoğan S. Vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor for renal scarring in recurrent urinary tract infections. Pediatr Int 2021; 63: 295-299. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.14397

- Flores ME, Rivera-Pasquel M, Valdez-Sánchez A, et al. Vitamin D status in Mexican children 1 to 11 years of age: an update from the Ensanut 2018-19. Salud Publica Mex 2021; 63: 382-393. https://doi.org/10.21149/12156

- World Health Organization (WHO). Application tools: growth reference data for 5-19 years. Geneva: WHO; 2025. Available at: https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years/application-tools (Accessed on Aug 10, 2025).

- Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, et al. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20: 629-637. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2008030287

- Chapter 1: definition and classification of CKD. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney International Supplements 2013; 3: 19-62. https://doi.org/10.1038/kisup.2012.64

- Moreau E, Bächer S, Mery S, et al. Performance characteristics of the VIDAS® 25-OH Vitamin D Total assay - comparison with four immunoassays and two liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry methods in a multicentric study. Clin Chem Lab Med 2016; 54: 45-53. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2014-1249

- Moorthy I, Wheat D, Gordon I. Ultrasonography in the evaluation of renal scarring using DMSA scan as the gold standard. Pediatr Nephrol 2004; 19: 153-156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-003-1363-2

- Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. Clin Chem 2015; 61: 1446-1452. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2015.246280

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): Guidelines. Urinary tract infection in under 16s: diagnosis and management. London: NICE; 2020.

- Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management; Roberts KB. Urinary tract infection: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics 2011; 128: 595-610. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1330

- Khazaei MR, Mackie F, Rosenberg AR, Kainer G. Renal length discrepancy by ultrasound is a reliable predictor of an abnormal DMSA scan in children. Pediatr Nephrol 2008; 23: 99-105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-007-0637-5

- Nahm FS. Receiver operating characteristic curve: overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean J Anesthesiol 2022; 75: 25-36. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.21209

- Schisterman EF, Faraggi D, Reiser B, Hu J. Youden Index and the optimal threshold for markers with mass at zero. Stat Med 2008; 27: 297-315. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2993

- Santini A, Man A, Voidăzan S. Accuracy of diagnostic tests. J Crit Care Med (Targu Mures) 2021; 7: 241-248. https://doi.org/10.2478/jccm-2021-0022

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ 2001; 79: 373-374.

- Reilly BM, Evans AT. Translating clinical research into clinical practice: impact of using prediction rules to make decisions. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144: 201-209. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-144-3-200602070-00009

- Steyerberg EW, Pencina MJ, Lingsma HF, Kattan MW, Vickers AJ, Van Calster B. Assessing the incremental value of diagnostic and prognostic markers: a review and illustration. Eur J Clin Invest 2012; 42: 216-228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02562.x

- Sherkatolabbasieh H, Firouzi M, Shafizadeh S, Nekohid M. Evaluation of the relationship between vitamin D levels and prevalence of urinary tract infections in children. New Microbes New Infect 2020; 37: 100728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100728

- Li X, Yu Q, Qin F, Zhang B, Lu Y. Serum vitamin D level and the risk of urinary tract infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health 2021; 9: 637529. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.637529

- Chidambaram S, Pasupathy U, Geminiganesan S, R D. The association between vitamin D and urinary tract infection in children: a case-control study. Cureus 2022; 14: e25291. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.25291

- Hewison M. Vitamin D and the immune system: new perspectives on an old theme. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2010; 39: 365-79, table of contents. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2010.02.010

- Shalaby SA, Handoka NM, Amin RE. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with urinary tract infection in children. Arch Med Sci 2018; 14: 115-121. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2016.63262

- Mahmoudzadeh H, Nikibakhsh AA, Pashapour S, Ghasemnejad-Berenji M. Relationship between low serum vitamin D status and urinary tract infection in children: a case-control study. Paediatr Int Child Health 2020; 40: 181-185. https://doi.org/10.1080/20469047.2020.1771244

- Mahyar A, Ayazi P, Safari S, Dalirani R, Javadi A, Esmaeily S. Association between vitamin D and urinary tract infection in children. Korean J Pediatr 2018; 61: 90-94. https://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2018.61.3.90

- AlGhamdi SA, Enaibsi NN, Alsufiani HM, Alshaibi HF, Khoja SO, Carlberg C. A single oral vitamin D3 bolus reduces inflammatory markers in healthy saudi males. Int J Mol Sci 2022; 23: 11992. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911992

- Megha KB, Joseph X, Akhil V, Mohanan PV. Cascade of immune mechanism and consequences of inflammatory disorders. Phytomedicine 2021; 91: 153712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153712

- Mohanty S, Kamolvit W, Hertting O, Brauner A. Vitamin D strengthens the bladder epithelial barrier by inducing tight junction proteins during E. coli urinary tract infection. Cell Tissue Res 2020; 380: 669-673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-019-03162-z

- Rosen CJ. Clinical practice. Vitamin D insufficiency. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 248-254. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1009570

- National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Vitamin D. 2018 [updated Sep18, 2023; Jan14, 2024]. Available at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional

- Vieth R. Critique of the considerations for establishing the tolerable upper intake level for vitamin D: critical need for revision upwards. J Nutr 2006; 136: 1117-1122. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.4.1117

- Braegger C, Campoy C, Colomb V, et al. Vitamin D in the healthy European paediatric population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013; 56: 692-701. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0b013e31828f3c05

- Martin CA, Gowda U, Renzaho AM. The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among dark-skinned populations according to their stage of migration and region of birth: a meta-analysis. Nutrition 2016; 32: 21-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2015.07.007

- Bahrami A, Sadeghnia HR, Tabatabaeizadeh SA, et al. Genetic and epigenetic factors influencing vitamin D status. J Cell Physiol 2018; 233: 4033-4043. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.26216

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.