Graphical Abstract

Abstract

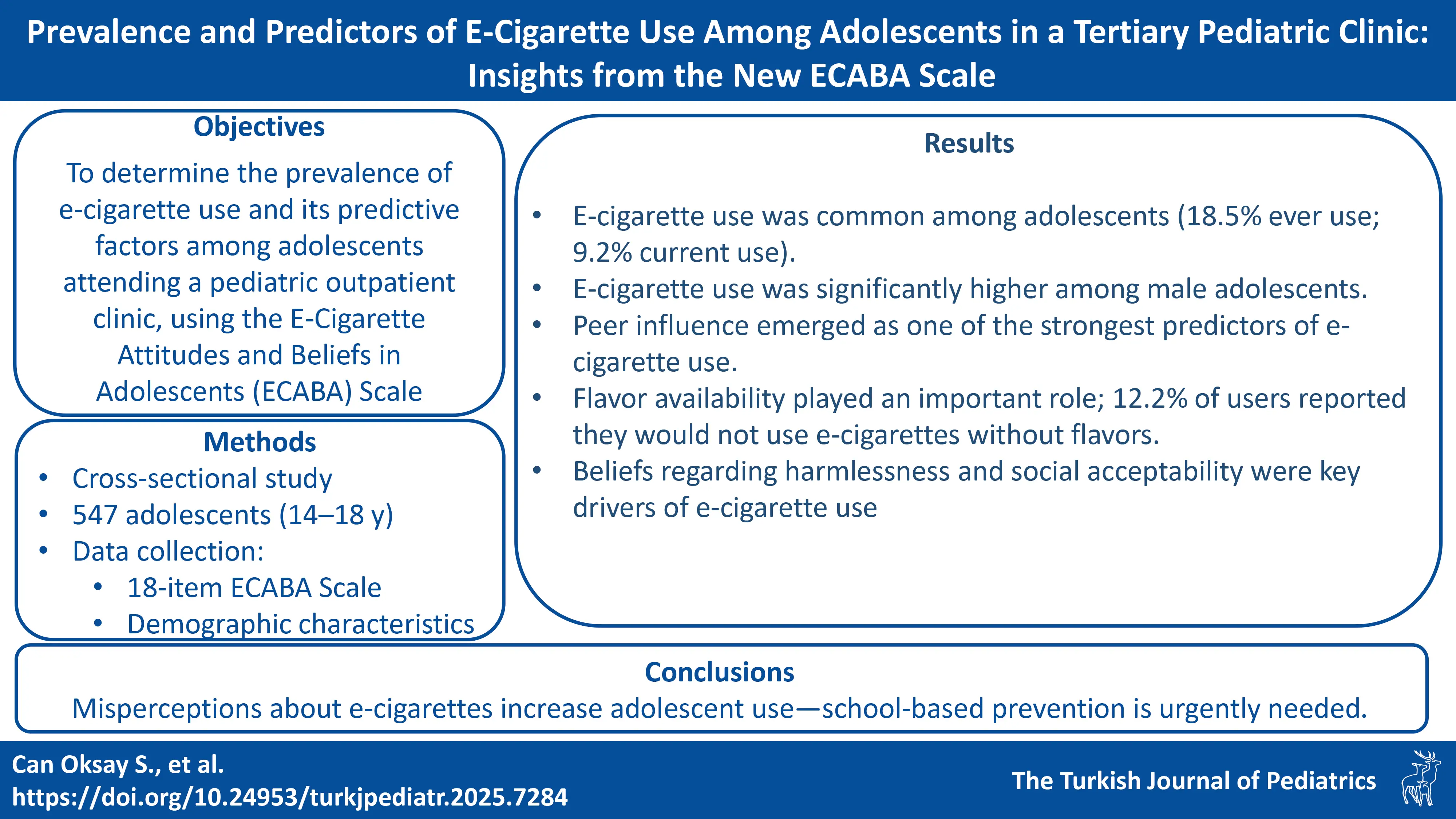

Background. Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are rapidly infiltrating youth culture under the guise of safety and social acceptance. Despite their prohibition in Türkiye, anecdotal reports suggest widespread access and experimentation among adolescents. This study aimed to determine the prevalence and predictors of e-cigarette use among adolescents attending a tertiary pediatric clinic, using the validated E-Cigarette Attitudes and Beliefs in Adolescents (ECABA) Scale to explore how beliefs shape behavior.

Methods. A cross-sectional design with consecutive sampling was employed. A total of 547 adolescents aged 14–18 years without psychological or organic illness participated. Data were collected using the 18-item ECABA Scale, along with demographic, cigarette, and e-cigarette use information. Logistic regression models were used to identify independent predictors of ever and current e-cigarette use.

Results. E-cigarette use was alarmingly common: 18.5% had ever tried, and 9.2% were current users. Males and those with peers who smoked or vaped were significantly more likely to use e-cigarettes (p<0.001). Higher ECABA total scores, reflecting more favorable attitudes, independently predicted both ever and current use (odds ratios 1.054 and 1.048 per unit increase, respectively). Subscales related to perceived physical harmlessness and social acceptance also emerged as significant predictors.

Conclusions. Adolescents who view e-cigarettes as harmless or socially acceptable are substantially more likely to use them, despite national restrictions. These findings expose a critical gap in prevention efforts and call for urgent school-based interventions to challenge the illusion of “safe vaping.” The ECABA Scale may serve as an effective early warning tool to identify at-risk youth before nicotine dependence takes hold.

Keywords: adolescents, attitudes; belief, e-cigarettes, predictors, public health

Introduction

Nicotine addiction has reinvented itself. Once confined to tobacco cigarette smoking, it now hides behind colorful flavors, sleek devices, and the illusion of safety. Worldwide, electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) have become the Trojan horse of the tobacco industry—marketing addiction as innovation, and vulnerability as freedom. Nowhere is this more alarming than among adolescents, a group deliberately targeted by advertising strategies that portray vaping as harmless, trendy, and socially acceptable.1,2 As a result of these strategies, by 2024, in the United Kingdom, 18% of individuals aged 11–17 had tried e-cigarettes at least once, and 7.2% were identified as current users. In the United States, e-cigarette use among high school students increased from 1.5% in 2011 to 16.0% in 2015.3 Although data are more limited in Asian countries, the reported prevalence of ‘ever users’ among adolescents ranges from 3.5% to 32%, reflecting regional and cultural variations.4 In Türkiye, data on e-cigarette use among adolescents are limited. Although no nationally representative study assesses the prevalence of e-cigarette use in Türkiye, a local survey of high school students reported a prevalence of 15.4%.5 The increasing prevalence of e-cigarette use among adolescents was highlighted in the 2023 report by the World Health Organization, which emphasized the urgency of taking immediate action in response to this concerning trend.6

A multinational study showed that adolescent experimentation greatly increases the risk of adult smoking.7 Among adolescents, key factors contributing to the initiation of e-cigarette use include the desire for social acceptance, curiosity, peer influence, the appeal of flavored products, and the impact of persuasive marketing strategies delivered through social media.8 However, due to cultural differences, patterns of e-cigarette use and the factors influencing such behavior may vary in our country. Against this backdrop, understanding how adolescents perceive e-cigarettes is not merely an academic exercise but a public health imperative. Beliefs about harm and social acceptance strongly influence experimentation and sustained use, yet culturally grounded data from Türkiye are lacking.

The primary aim of this study was to determine the prevalence and predictors of e-cigarette use among adolescents attending a tertiary pediatric outpatient clinic. The secondary aim was to explore the relationship between adolescents’ beliefs and attitudes toward e-cigarettes—measured by the validated E-Cigarette Attitudes and Beliefs in Adolescents (ECABA) Scale9, and their actual use behaviors.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional, scale-based study was conducted between May and September 2025 at the pediatric outpatient clinics of a tertiary hospital in İstanbul, Türkiye. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Before starting the study, it was approved by the Istanbul Medipol University Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 645, dated May 22, 2025). Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians, and age-appropriate assent was obtained from all participating adolescents.

Participants and data collection

Adolescents aged 14–18 years who presented to the pediatric outpatient clinic for non-urgent visits and were not diagnosed with chronic physical or psychiatric disorders were invited to participate. Those who agreed to take part were first provided with an information sheet outlining the study and the questionnaires involved. In line with voluntary participation principles, individuals who did not provide consent or who submitted incomplete scales were excluded from the study. No financial or other incentives were offered to participants.

Sociodemographic and Behavioral Variables: Participants completed a structured questionnaire including demographic characteristics (age, gender, academic grade level, monthly household income, parental education level), self-reported knowledge about e-cigarettes, and smoking exposure variables (household smoking, close friends who smoke or use e-cigarettes, and frequency of use). Apart from age and gender, no personal identifying information was collected. The term ‘smoking’ refers exclusively to tobacco cigarette smoking, whereas the terms ‘vaping’ and ‘e-cigarette use’ are used to describe the use of electronic cigarettes. Participants were asked to self-rate their knowledge of e-cigarettes as ‘none,’ ‘low,’ ‘moderate,’ or ‘high.’ These categories reflected participants’ perceptions of their knowledge rather than objective testing; no examples, images, or definitions were provided to avoid inadvertently educating or encouraging experimentation. ‘High knowledge’ thus corresponds to participants’ subjective assessment of being well-informed about e-cigarettes. To capture further how they learned about e-cigarettes, participants were also asked to report the source from which they first acquired this information; response options were coded as follows: friends (1), family (2), printed media (3), social media (4), online advertisements (5), and observing someone using an e-cigarette (6).

The terms ‘ever smoked’ and ‘ever e-cigarette use’ were used to describe individuals who had experimented with packaged cigarettes or e-cigarettes at any point in their lives. ‘Current smoking’ and ‘current e-cigarette use’ were defined as use within the past 30 days. In our study, academic grade level (9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th grades), monthly household income (<40,000 TRY, 40,000–60,000 TRY, >60,000 TRY; with the minimum wage in Türkiye being approximately 22,000 TRY), parental education level (illiterate, primary–middle school, high school–university), self-reported knowledge about e-cigarettes (none, low, moderate, high), and frequency of smoking or e-cigarette use (<1/week, 2–4/week, >4/week) were categorized and treated as ordinal variables.

ECABA Scale: As the data collection tool, the 18-item ‘E-Cigarette Adolescent Beliefs and Attitudes (ECABA) Scale,’ previously validated and shown to be reliable, was employed.9 This scale is the first instrument developed explicitly in Türkiye for this age group. In the “E-cigarette Attitude and Belief Scale in Adolescents: A Validity and Reliability Study”, Cronbach’s alpha values were evaluated with a tiered approach: ≥ 0.90 excellent, ≥ 0.80 good, ≥0.70 acceptable, ≥ 0.60 questionable, ≥ 0.50 poor, and ≤ 0.50 unacceptable.10 The internal consistency of the final version of the scale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. A final exploratory factor analysis, conducted after removing semantically inconsistent items, yielded a five-factor structure comprising 18 items, all demonstrating satisfactory factor loadings (>0.50) and strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.88) (Supplementary Table S1).9 The ECABA Scale is divided into five subscales: Physical Consequences of E-Cigarette, E-Cigarette versus Packaged Cigarettes (EC vs. PC), Establishing Identification, E-Cigarette Addiction, and Socialization.9 Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’), with higher scores indicating more positive beliefs and attitudes toward e-cigarettes among adolescents. To provide readers with a better understanding of each subscale, representative items include: Physical Consequences of EC: ‘E-cigarettes do not cause headache’; EC vs. PC: ‘E-cigarettes do not contain nicotine, unlike classic cigarettes’; Establishing Identification: ‘Seeing influencers use e-cigarettes makes me think more positively about them’; EC Addiction: ‘E-cigarettes do not contain harmful or addictive substances’; and Socialization: ‘There is no problem in using e-cigarettes to avoid being excluded from your circle of friends. The full 18-item ECABA Scale in English is provided as Supplementary Table S2.

Statistical analyses

The minimum required sample size for the study was calculated as 384 participants using the G*Power software (version 3.1), based on a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. Participants were recruited through a consecutive sampling method. To enhance reliability and account for potential exclusions, data were collected from a number of participants exceeding the calculated minimum requirement.

The demographic characteristics and descriptive attributes of the participants, as well as individual characteristic groups, were summarized using descriptive statistics such as frequency, percentage, and median with interquartile range. The normality of the data was assessed using graphical methods and Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality tests. Depending on the data distribution, either parametric or non-parametric tests were applied. For comparisons of total and subscale scores of the ECABA Scale across different demographic and individual characteristic groups, the independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was used for two-group comparisons, and one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test for comparisons involving more than two groups.

When a significant difference was detected in the ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests, Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests were performed to identify the source of the difference. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) was used to examine the relationships between ordinal variables and the total and subscale scores of the ECABA Scale. Our multivariable model was constructed by first including mandatory confounders identified a priori based on the literature and public health relevance (age, gender, and household income). In addition to these core variables, other potential covariates were evaluated using a change-in-estimate approach. Variables that altered the odds ratio (OR) of the primary independent variable by more than 10% upon inclusion—specifically, having close friends who smoke or use e-cigarettes, household smoking, and exposure to environments where e-cigarettes are used—were retained in the final multivariable model. Binary logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate whether ECABA scores could predict ‘current’ (currently using) and ‘ever’ (previously used) smoking and e-cigarette use. The first model (unadjusted) examined the bivariate relationship between each ECABA total and subscale score and cigarette or e-cigarette use. The analysis results were reported as OR with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

A total of 662 adolescents were invited to participate in the study. Of these, 73 were excluded due to diagnosed chronic illnesses or lack of assent/parental consent. Among the remaining 589 adolescents, 42 were excluded due to incomplete responses on the scale. Consequently, the final study population consisted of 547 adolescents. A total of 547 adolescents with a median age of 16 (min-max: 14-18) years old participated in this scale. The female population comprised 51.4% (n = 281) of the participants. The participants’ sociodemographic characteristics and environmental exposures are summarized in Table I. The most common sources where adolescents learned about e-cigarettes were, in order, friends, observing someone using them, and social media (respectively, 34.0%, 18.2%, 14.1%).

| EC: electronic cigarette, IQR: interquartile range, TRY: Turkish Liras | |

| Table I. Characteristics, features, and demographic groups of the participants (N=547). | |

|

|

|

| Age (year), median (min-max) |

|

| Female gender |

|

| Academic grade | |

| 9th |

|

| 10th |

|

| 11th |

|

| 12th |

|

| Monthly income | |

| <40000 TRY |

|

| 40-60000 TRY |

|

| >60.000 TRY |

|

| Mother educational grade | |

| Illiterate |

|

| Primary-secondary school |

|

| High school-university |

|

| Father educational level | |

| Illiterate |

|

| Primary-secondary school |

|

| High school-university |

|

| Peer and Household Exposures | |

| Close friend, EC using |

|

| Close friend, smoking |

|

| Ever exposure to EC use |

|

| Household exposure to tobacco smoke |

|

| EC self-rated knowledge level | |

| None |

|

| Low |

|

| Moderate |

|

| High |

|

| Number of smokers in the household | |

| Single smoker |

|

| Multiple smokers |

|

| E-cigarette use | |

| Ever used EC |

|

| Current EC using (past 30 days) |

|

| Frequency of EC use | |

| Once per week |

|

| 2–4 times per week |

|

| >4 times per week |

|

| Tobacco cigarette use | |

| Ever smoked |

|

| Current smoking (past 30 days) |

|

| Frequency of smoking | |

| Once per week |

|

| 2–4 times per week |

|

| >4 times per week |

|

Prevalence of e-cigarette use and smoking

Of all participants,18.5% of adolescents reported having ever used an e-cigarette, and 9.2% were current users within the past 30 days. For packaged cigarettes, the rates were slightly higher: 20.9% ever users and 14.4% current smokers. Table I presents the frequency of current e-cigarette use and smoking. Twelve point two percent of participants stated that they would not use e-cigarettes if they were not flavored.

Sociodemographic predictors of e-cigarette use

Male adolescents were significantly more likely to have ever or currently used e-cigarettes compared with females (p < 0.001). E-cigarette use increased progressively with higher academic grade levels (p = 0.023). Adolescents reporting “high knowledge” about e-cigarettes paradoxically had higher odds of use (p < 0.001). Peer influence was one of the strongest predictors: those with friends who used e-cigarettes were almost twice as likely to report ever vaping (p < 0.001).

Association between ECABA Scale scores and e-cigarette use/smoking

Table II presents a comparison of the ECABA Scale total and subscale scores according to gender, grade level, and smoking and e-cigarette use status. Male participants were more likely to believe that e-cigarettes positively contribute to socialization (p< 0.001). Participants whose close friends smoked cigarettes or used e-cigarettes demonstrated statistically significantly more positive beliefs and attitudes toward e-cigarettes across the total ECABA Scale score and all subscales (Table II). Individuals who had ever smoked or used e-cigarettes demonstrated statistically significantly more positive beliefs and attitudes toward e-cigarettes. Additionally, current e-cigarette users showed statistically significant positive responses specifically on the Physical Consequences of E-Cigarette subscale (p=0.022).

|

Scores presented as median (interquartile range). EC: electronic cigarette. ECABA: E-Cigarette Attitudes and Beliefs in Adolescents, PC: packaged cigarette. |

|||||||

| Table II. Comparison of total and subscale scores of ECABA Scale across characteristics, and demographic groups. | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Gender | Male |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Female |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Academic grade | 9th |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 10th |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 11th |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 12th |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Household exposure to smoking | No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Number of smokers in the household | Single |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Multiple |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Close friend, smoking | No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Close friend, EC using | No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ever used EC | No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Current EC using (past 30 days) | No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ever smoking | No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Current smoking (past 30 days) | No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table III presents correlations of ordinal variables with total and subscale scores of ECABA Scale. As academic grade level increased, participants demonstrated statistically significantly more positive responses to the Physical Consequences of E-Cigarette subscale items (p=0.023). As paternal education level increased, statistically significant increases in positive responses were observed in the scores (Table III). Additionally, we found that higher adolescent self-reported knowledge about e-cigarettes was associated with statistically significant more positive beliefs and attitudes across all scores (respectively, p<0.001, p<0.001, p<0.001, p<0.001, p=0.029, p=0.003). As the frequency of e-cigarette use increased, statistically significant positive beliefs and attitudes were observed in the total score, three of the subscale scores (respectively, p=0.013, p=0.006, p=0.012, p=0.019) (Table III).

|

Values represent ρ (Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient) EC: electronic cigarette. PC: packaged cigarette. |

||||||

| Table III. Correlations of ordinal variables with total and subscale scores. | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Academic grade |

|

(p=0.023) |

|

|

|

|

| Monthly income |

|

(p=0.940) |

|

|

|

|

| Mother educational level |

|

(p=0.544) |

|

|

|

|

| Father educational level |

|

(p=0.026) |

|

|

|

|

| EC knowledge level |

|

(p=<0.001) |

|

|

|

|

| Frequency of EC using |

|

(p=0.006) |

|

|

|

|

| Frequency of smoking |

|

(p=0.450) |

|

|

|

|

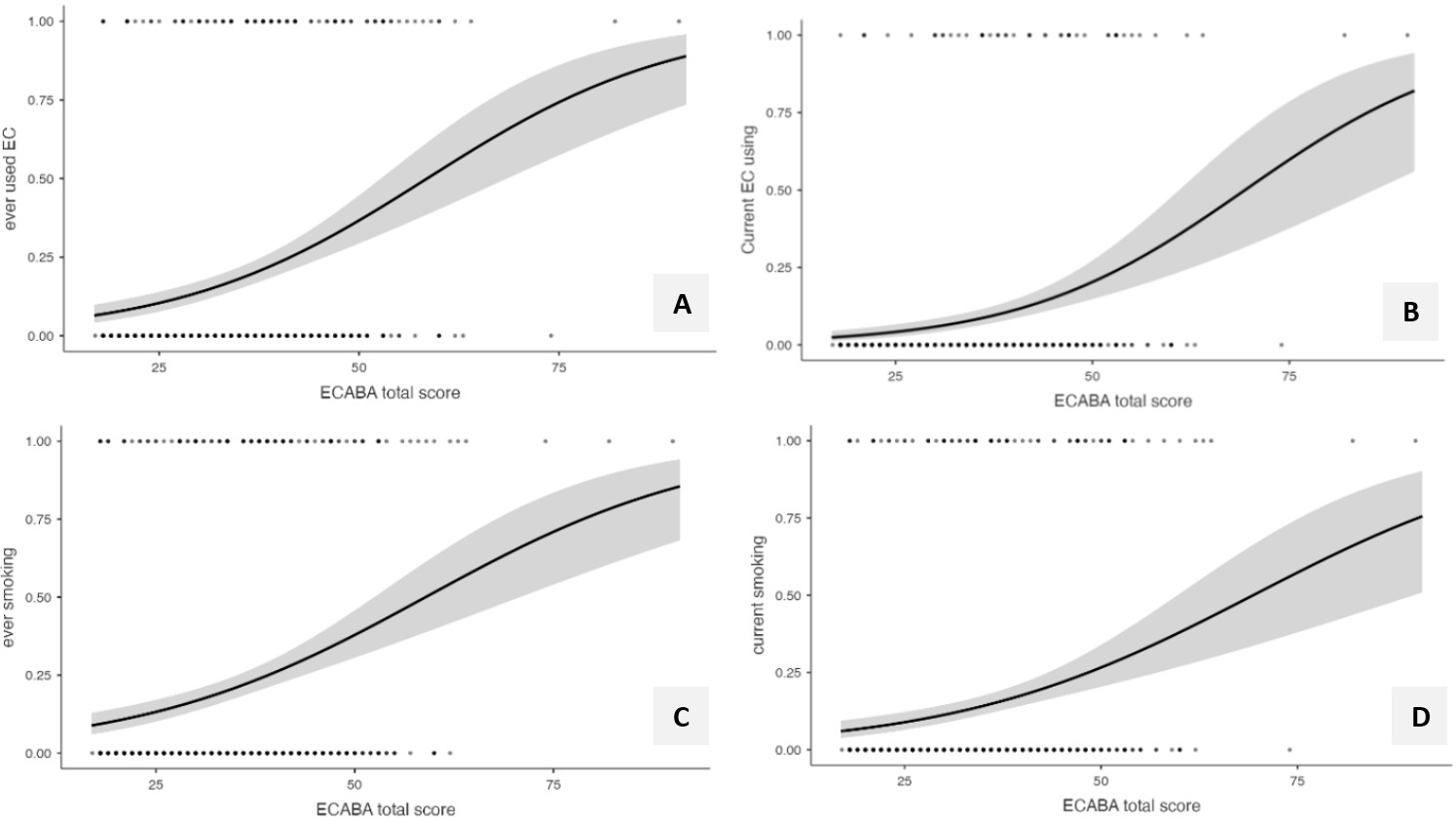

Crude and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to determine whether increases in the total and subscale scores constitute independent risk factors for e-cigarette and tobacco cigarette smoking. In the crude model, each one-point increase in the ECABA Scale total score was associated with an approximately 6.6% increase in the likelihood of ever using an e-cigarette (p < 0.001) (OR = 1.066, 95% CI: 1.045-1.087) (Table IV). In the multivariate analysis, independent of demographic and social factors, the ECABA total score remained as a significant predictor, where each one-point increase was associated with a 4.6% higher likelihood of ever using e-cigarettes (OR = 1.046, p = 0.003), a 5.4% higher likelihood of ever smoking (OR = 1.054, p < 0.001), a 4.8% higher likelihood of being a current e-cigarette user (OR = 1.048, p = 0.007), and a 5.5% higher likelihood of being a current smoker (OR = 1.055, p < 0.001).

| CI: confidence interval, EC: electronic cigarette, ECABA: E-Cigarette Attitudes and Beliefs in Adolescents, OR: odds ratio, PC: packaged cigarette. | ||||||||

| Table IV. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis for using e-cigarette / tobacco cigarette smoking. | ||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| ECABA Total or Subscale Scores |

(95% CI) |

|

(95% CI) |

|

(95% CI) |

|

(95% CI) |

|

| ECABA Total Score |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Physical Consequences |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EC vs. PC |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Establishing Identification |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| EC Addiction |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Socialization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|||||||

| ECABA Total or Subscale Scores |

(95% CI) |

|

(95% CI) |

|

(95% CI) |

|

(95% CI) |

|

| ECABA Total Score |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Physical Consequences |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EC vs. PC |

|

|

||||||

| Establishing Identification |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EC Addiction |

|

|

|

|||||

| Socialization |

|

|

|

|||||

Among the subscales, the Physical Consequences subscale independently predicted both e-cigarette use and smoking (ever e-cigarette use: OR = 1.090, p = 0.025; current e-cigarette use: OR = 1.127, p = 0.037; ever smoking: OR = 1.113, p = 0.002; current smoking: OR = 1.130, p = 0.002). The Establishing Identification subscale was significantly associated with current e-cigarette use and smoking behavior (current e-cigarette use; OR = 1.363, p = 0.035, ever smoked: OR = 1.155, p = 0.015; current smoking: OR = 1.140, p = 0.043).

Fig. 1. demonstrates the logistic regression–based predicted probabilities of e-cigarette use and smoking across the range of ECABA total and subscale scores. As shown, higher ECABA Scale scores are significantly associated with both ever and current smoking. Total scores and the ‘Physical Consequences of E-Cigarette’ and ‘Establishing Identification’ subscales independently increase the likelihood of smoking, whereas other subscales show no significant associations.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated e-cigarette awareness, prevalence, and related beliefs among a large cohort of adolescents using the ECABA Scale, a validated national instrument explicitly designed for this population. Despite strict national regulations, we found that nearly one in five adolescents had experimented with e-cigarettes and almost one in ten were current users, underscoring the growing public health impact of vaping among youth in Türkiye. Beyond documenting prevalence, our findings highlight that adolescents’ perceptions—particularly beliefs related to physical harmlessness and social acceptability—play a central role in shaping e-cigarette behavior. Moreover, higher ECABA Scale scores were identified as predictors of both ever trying e-cigarettes and current e-cigarette use, underscoring the scale’s ability to capture attitudinal patterns that directly translate into behavioral outcomes.

When examining the sources through which participants learned about e-cigarettes, they primarily reported gaining information from their peer group, followed by observing others using e-cigarettes, and, thirdly, through social media. These findings highlight the significant influence of the social environment and exposure on adolescents’ perceptions and attitudes toward e-cigarettes.11 Adolescents who had been in settings where e-cigarettes were used, or who had close friends who used them, consistently demonstrated higher ECABA scores, reflecting more favorable beliefs and attitudes. This pattern aligns with previous research showing that peer use and social exposure are among the strongest predictors of adolescent e-cigarette initiation.12,13 Dual users—those who used both cigarettes and e-cigarettes—also exhibited markedly more favorable beliefs, a finding consistent with studies such as Hanafin et al. in Ireland, where smokers perceived e-cigarettes as a harm-reducing alternative.14 This suggests that product use may actively shape perceptions, reinforcing attitudes that portray e-cigarettes as less harmful. Similar findings from South Africa further indicate that adolescent e-cigarette users tend to view the product as harmless or ‘safer’ than packaged cigarettes.15 Collectively, these results highlight the powerful role of peer modeling, observational learning, and behavioral reinforcement in forming adolescents’ perceptions of e-cigarettes.

Another notable pattern was the association between higher academic grade levels and more positive beliefs regarding the physical consequences of e-cigarettes. Several factors may explain this pattern. Previous studies report that with increasing age and grade level, students tend to perceive the potential harms of e-cigarettes as less significant and normalize their use within this group.14-16 For instance, older high school students are more frequently exposed to online content and peer environments that portray e-cigarettes as less harmful. This exposure—coupled with increased autonomy, more unsupervised time with peers, and greater access to social media platforms where vaping-related promotional messages, influencer content, and harm-minimizing narratives are widespread—may gradually reduce perceived physical risks and contribute to higher subscale scores. Moreover, as adolescents grow older, the initial drivers of experimentation, such as curiosity or social pressure, may evolve into more personal motivations, including enjoyment, stress relief, and behavioral or physical dependence, further reinforcing positive beliefs and attitudes toward e-cigarettes. Taken together, these mechanisms are consistent with previous literature indicating that older adolescents are more likely to view e-cigarettes as less harmful and to normalize their use.

In our study, no significant relationship was found between maternal education level and positive beliefs or attitudes toward e-cigarettes. However, higher paternal education was associated with increased total ECABA Scale scores and subscale scores, particularly those reflecting beliefs related to physical health and comparisons with tobacco cigarette smoking. Previous findings on this topic are inconsistent: some studies report associations with maternal education,18 while others identify paternal education as the relevant factor.16,17 These discrepancies suggest that sociocultural context may shape how parental education influences adolescents’ perceptions of e-cigarettes.

The association between self-rated high knowledge and positive ECABA Scale scores warrants careful interpretation. We found that adolescents who reported having greater knowledge about e-cigarettes scored higher on the scale, indicating more positive beliefs and attitudes. It is important to note that the ‘high knowledge’ reported by adolescents likely reflects perceived knowledge, shaped by exposure to promotional or misleading online content, rather than an evidence-based understanding. Therefore, higher self-rated knowledge may actually indicate greater susceptibility to industry-driven narratives portraying e-cigarettes as harmless, which in turn contributes to more positive beliefs and attitudes. This likely reflects the widespread presence of misleading promotional content in industry-sponsored information.

In our study, increases in total ECABA Scale scores were identified as an independent predictor of a higher likelihood of ever trying e-cigarettes. The literature supports this finding; for example, one study reported that each one-unit increase in students’ positive attitude scores toward e-cigarettes was associated with a 15% increase in the likelihood of lifetime e-cigarette use.18

E-cigarette aerosols contain harmful chemicals such as nicotine, flavoring agents, tobacco-specific nitrosamines, heavy metals (nickel, tin, lead), volatile organic compounds, and formaldehyde, which can cause both acute and chronic physical damage.19 We found a significant positive association between participants’ belief that e-cigarettes are not physically harmful and having ever used e-cigarettes, as measured by the ‘Physical Consequences of E-Cigarette’ subscale. The literature also indicates that young e-cigarette users are twice as likely as non-users to believe that e-cigarettes are harmless.1,20,21 Such misperceptions may serve as cognitive justifications that facilitate initiation, enabling adolescents to minimize or dismiss potential physical risks and align their beliefs with their behavior. These attitudes may also stem from widespread harm-minimizing messages in social media and marketing, which frame e-cigarettes as ‘safer’ alternatives and contribute to reduced risk perception among youth.

In our study, each one-unit increase in the ‘Physical Consequences of E-Cigarette’ subscale score was associated with an increased risk of current e-cigarette use. Consistent with prior research, this finding indicates that adolescents who minimize the physical harms of e-cigarettes are at greater risk of ongoing use.20,22 We also observed that higher scores on the ‘Socialization’ subscale predicted current use, indicating that adolescents who view e-cigarettes as socially facilitating may be more inclined to use them. This aligns with those of Bernat et al., who reported that 15% of high school students aged 14–17 perceived e-cigarette users as having more friends and being cooler—a proportion that increased to 25% among current e-cigarette users.23 These findings resonate with prior literature showing that risk minimization and social acceptance are key cognitive distortions among adolescent users. What is new here is that these associations were observed using a culturally adapted and validated scale, offering one of the first real-world applications of the ECABA Scale as a behavioral screening tool.

Our study demonstrated that each one-point increase in the total ECABA Scale score was associated with higher odds of both ever smoking and current smoking, suggesting that positive beliefs and attitudes toward e-cigarettes may generalize to combustible tobacco use behaviors. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that favorable perceptions of alternative nicotine products, such as e-cigarettes, can reduce risk perceptions related to tobacco cigarette smoking and potentially facilitate smoking initiation, particularly among adolescents.24 Such cross-product normalization highlights that misconceptions about e-cigarettes may have broader implications beyond vaping itself, underscoring the need for prevention strategies that address risk perception across multiple forms of nicotine use.

In our study, scores on the ‘Physical Consequences of E-Cigarette’ and ‘Establishing Identification’ subscales were significantly and positively associated with the likelihood of having ever smoked and being a current smoker. This suggests that increased beliefs in the low physical harm of e-cigarettes and greater identification with e-cigarette use are linked to higher probabilities of ever smoking and current smoking. The literature indicates that positive attitudes toward e-cigarettes may contribute to decreased risk perception of nicotine products overall among adolescents, thereby facilitating transitions to other tobacco products such as cigarettes.24 In this context, positive beliefs toward e-cigarette use may not be confined to vaping behavior alone. Still, they could also play a role in the transition to more harmful tobacco products such as cigarettes, potentially increasing the risk of dual use during this process.

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design prevents establishing causal relationships among beliefs, attitudes, and e-cigarette use. Second, data were self-reported, which may introduce recall bias or social desirability bias, potentially leading to under- or over-reporting of e-cigarette use and related behaviors. Third, the study was conducted in a single region and may not be fully generalizable to all adolescents in Türkiye. Nonetheless, the sample size was robust, and the findings provide essential baseline data for future population-based studies. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the magnitude and direction of the associations observed. The strength of the study is that this is the first study in Türkiye to evaluate adolescent e-cigarette use using a validated national-scale instrument. It has a large, well-characterized sample allowing meaningful subgroup comparisons. Unlike many prevalence studies, this research simultaneously examined behavioral prevalence and psychosocial predictors, linking beliefs directly to actual use behaviors.

Conclusion

The normalization of e-cigarette use among adolescents, even in a legally restricted setting, exposes a silent failure in tobacco control. Total ECABA Scale scores independently predicted current e-cigarette use, supporting its value in identifying at-risk youth. Beliefs in physical harmlessness and social acceptance are robust psychological gateways to nicotine initiation. The ECABA Scale proved useful in identifying these misperceptions and could serve as an early-warning tool within school or clinic settings. Future multicenter and population-based studies are urgently needed to expand these findings and guide national prevention policies. Unless preventive action keeps pace with the industry’s adaptation, we risk losing a generation not to ignorance, but to illusion—the illusion that vaping is different.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

We acknowledge that we employed ChatGPT 4 to assist us in refining the clarity of our writing while developing the draft of this original article. We always maintained continuous human oversight (editing and revising) and verified the AI-generated output.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Istanbul Medipol University Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (date: May 22, 2025, number: 645).

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Greenhill R, Dawkins L, Notley C, Finn MD, Turner JJD. Adolescent awareness and use of electronic cigarettes: a review of emerging trends and findings. J Adolesc Health 2016; 59: 612-619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.08.005

- Doherty J, Davison J, McLaughlin M, et al. Prevalence, knowledge and factors associated with e-cigarette use among parents of secondary school children. Public Health Pract (Oxf) 2022; 4: 100334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2022.100334

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette use among youth and young adults - a report of the surgeon general. 2016. Available at: https://escholarship.org/content/qt9p15c3w3/qt9p15c3w3.pdf (Accessed on July 19, 2025).

- Ko K, Ting Wai Chu J, Bullen C. A Scoping review of vaping among the Asian adolescent population. Asia Pac J Public Health 2024; 36: 664-675. https://doi.org/10.1177/10105395241275226

- Kurtuluş Ş, Can R. Use of e-cigarettes and tobacco products among youth in Turkey. Eurasian J Med 2022;54:127-132. https://doi.org/10.5152/eurasianjmed.2022.20168

- World Health Organization (WHO). Urgent action needed to protect children and prevent the uptake of e-cigarettes. 2023. Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-12-2023-urgent-action-needed-to-protect-children-and-prevent-the-uptake-of-e-cigarettes

- Chen X, Yu B, Wang Y. Initiation of electronic cigarette use by age among youth in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2017; 53: 396-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.02.011

- Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Cornelius M, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students - national youth tobacco survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Surveill Summ 2022; 71: 1-29. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7105a1

- Can Oksay S, Alpar G, Bilgin G, Tortop DM, Onay ZR, Gürler E. E-cigarette attitude and belief scale in adolescents: a validity and reliability study. Turk Thorac J 2025; 26: 290-297. https://doi.org/10.4274/ThoracResPract.2025.2025-5-5

- Mallery P, George D. SPSS for Windows step by step. United States: Allyn & Bacon, Inc; 2000. Available at: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/557542 (Accessed on December 18, 2024).

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predictiing social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980.

- Valente TW, Piombo SE, Edwards KM, Waterman EA, Banyard VL. Social network influences on adolescent e-cigarette use. Subst Use Misuse 2023; 58: 780-786. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2023.2188429

- Dilektasli AG, Guclu OA, Ozpehlivan A, et al. Electronic cigarette use and consumption patterns in medical university students. Front Public Health 2024; 12: 1403737. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1403737

- Hanafin J, Sunday S, Clancy L. Sociodemographic, personal, peer, and familial predictors of e-cigarette ever use in ESPAD Ireland: a forward stepwise logistic regression model. Tob Induc Dis 2022; 20: 12. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/144234

- van Zyl-Smit RN, Filby S, Soin G, Hoare J, van den Bosch A, Kurten S. Electronic cigarette usage amongst high school students in South Africa: a mixed methods approach. EClinicalMedicine 2024; 78: 102970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102970

- Kurdyś-Bykowska P, Kośmider L, Bykowski W, Konwant D, Stencel-Gabriel K. Epidemiology of traditional cigarette and e-cigarette use among adolescents in Poland: analysis of sociodemographic risk factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024; 21: 1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21111493

- AlMuhaissen S, Mohammad H, Dabobash A, Nada MQ, Suleiman ZM. Prevalence, knowledge, and attitudes among health professions students toward the use of electronic cigarettes. Healthcare (Basel) 2022; 10: 2420. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122420

- Vichayanrat T, Chidchuangchai W, Karawekpanyawong R, Phienudomkitlert K, Chongcharoenjai N, Fungkiat N. E-cigarette use, perceived risks, attitudes, opinions of e-cigarette policies, and associated factors among Thai university students. Tob Induc Dis 2024; 22: 10.18332/tid/186536. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/186536

- Bush A, Lintowska A, Mazur A, et al. E-cigarettes as a growing threat for children and adolescents: position statement from the European Academy of Paediatrics. Front Pediatr 2021; 9: 698613. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.698613

- Aly AS, Mamikutty R, Marhazlinda J. Association between harmful and addictive perceptions of e-cigarettes and e-cigarette use among adolescents and youth-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Children (Basel) 2022; 9: 1678. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111678

- Cornelia M, Alexandra C, Ioana-Cristina P. It´s harmless! The reasons behind vaping behavior among youth: risks, benefits, and associations with psychological distress. Psihologija. Forthcoming 2025. https://doi.org/10.2298/PSI230824013M

- Bluestein MA, Harrell MB, Hébert ET, et al. Associations between perceptions of e-cigarette harmfulness and addictiveness and the age of e-cigarette initiation among the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) youth. Tob Use Insights 2022; 15: 1179173X221133645. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179173X221133645

- Bernat D, Gasquet N, Wilson KO, Porter L, Choi K. Electronic cigarette harm and benefit perceptions and use among youth. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55: 361-367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.043

- Wills TA, Knight R, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Pagano I, Williams RJ. Longitudinal study of e-cigarette use and onset of cigarette smoking among high school students in Hawaii. Tob Control 2017; 26: 34-39. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052705

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.