Abstract

Background. Pediatric sepsis is a heterogeneous syndrome; data on early biomarker kinetics and their link to severity are scarce.

Methods. We prospectively enrolled 80 children with sepsis (March 2022 – June 2024). C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), interleukin-6 (IL-6), serum amyloid-A (SAA), and D-dimer were measured at admission (T0), 72 hours (T1) later and on Day 7 (T2). Disease severity was assessed using the pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (pSOFA); length of stay (LOS) was recorded. Baseline values, Day 7 levels, and changes Δ(T2–T0) were correlated with pSOFA and LOS.

Results. Baseline inflammatory profiles differed by etiology: median CRP and PCT on admission were roughly doubled in bacterial versus viral disease, while IL‑6 was highest in respiratory and abdominal infections. Nevertheless, all six markers decreased significantly over seven days (p ≤ 0.015) and the proportional declines were uniform across pathogens or foci (interaction p > 0.18). Higher admission CRP, PCT, IL‑6 and D‑dimer modestly correlated with greater organ dysfunction (r ≤ 0.55), whereas steeper week‑long falls in the same markers tracked with larger pSOFA improvement (r = –0.41 to –0.53; all p ≤ 0.002). SAA showed a weaker inverse association (r = –0.32, p = 0.008), whereas the decline in ESR was not significant. A pragmatic two‑step algorithm (admission CRP ≥ 60 mg/L, PCT ≥ 3 ng/mL, IL‑6 ≥ 200 pg/mL or D‑dimer ≥ 1.5 mg/L; plus a ≥ 50% drop in IL‑6 or PCT within 72 h) identified children who ultimately required intensive care unit (ICU) care or stayed ≥ 7 days with an area‑under‑the‑curve of 0.91.

Conclusions. Both initial elevations and early declines in CRP, PCT, IL-6 and D-dimer mirror organ dysfunction and hospitalization duration in pediatric sepsis. Serial monitoring of these readily available markers may improve early risk stratification and guide therapy.

Keywords: pediatric sepsis, dynamic plasma biomarkers, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, interleukin-6

Introduction

Pediatric sepsis is an infection driven systemic inflammatory response that can quickly lead to organ failure and shock. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign criteria and the pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (pSOFA) score remain the main tools for grading severity.1-3 Yet sepsis is still one of the top causes of childhood death worldwide.1,4 Age related immune maturation shapes infection risk and disease course, making early diagnosis and precise risk stratification—and therefore timely treatment—difficult.5-7.

Biomarkers underpin early diagnosis, therapy monitoring, and prognosis in sepsis, with serial measurements offering clearer views of response and disease course.8,9 In children, key analytes include C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), interleukin-6 (IL-6), serum amyloid-A (SAA), and D-dimer.7,8 Although these tests sharpen diagnostic accuracy, they often require specialized assays and may encourage antibiotic overuse.7 Composite panels can improve early screening but remain costly and unstandardized, highlighting the need for affordable, validated multimarker workflows across diverse pediatric populations.7 Biomarker work in sepsis has focused mainly on adults, where markers such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-1 (sFlt 1) reliably flag poor outcomes.10 Pediatric evidence is limited—only a handful of studies profile biomarkers in children.11-13 Even fewer link serial declines to clinical recovery.14 Comprehensive pediatric studies across illness severities are needed to sharpen risk stratification and tailor care.

The six biomarkers—CRP, SAA, PCT, IL-6, ESR, and D-dimer—represent distinct yet complementary pathways in the pathophysiology of sepsis, facilitating early diagnosis and management in pediatric patients. These biomarkers are routinely available within a 24-hour laboratory panel, with a turnaround time of less than two hours.15 Competing candidates like presepsin and pro-adrenomedullin were excluded due to the lack of robust pediatric reference ranges or higher costs.16 Studies indicate that IL-6 and PCT are particularly effective in distinguishing bacterial infections, while combinations of these biomarkers can yield high predictive values for sepsis severity.8,17

We aimed to track six biomarkers —CRP, PCT, IL-6, SAA, ESR, and D-dimer— over the first seven days of pediatric sepsis and see how their trends match pSOFA scores. We also tested whether these patterns predicted length of stay, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and major complications. We expect high baseline levels and slow declines to signal worse illness and longer hospital stays, while faster falls should coincide with recovery.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

We carried out a single center, prospective observational study in the Department of Pediatrics, Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University, from March 2022 to June 2024. Consecutive children who met consensus diagnostic criteria for sepsis were enrolled and followed prospectively. Key inflammatory biomarkers were quantified at predefined time points from admission through Day 7, alongside detailed clinical assessments. All procedures adhered to institutional pediatric sepsis pathways and local standards of care.

The protocol was approved by the Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Before enrolment, the child’s parents or legal guardians received a comprehensive explanation of the study’s objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits, and subsequently provided written informed consent. All participant data were anonymized to safeguard confidentiality.

Inclusion Criteria:

- Children aged 1 month to 14 years were considered eligible if they presented with clinical signs of sepsis, according to the International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference (IPSCC) criteria, i.e., suspected/proven infection plus ≥ 2 age-adjusted systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria (abnormal temperature or leukocyte count mandatory).18

- Children who had a documented need for inpatient care, and were able to undergo serial blood sampling at the designated time points

- Patients were included irrespective of infection source or pathogen type, as long as the attending pediatrician deemed sepsis the most likely clinical diagnosis

- Additional requirements included the ability of a parent or legal guardian to provide signed informed consent within 24 hours of admission

- Willingness to comply with the study protocol.

Exclusion Criteria:

- Children with known severe primary immunodeficiency

- Children who were receiving or had recently received high-dose immunosuppressive therapy

- Children with documented malignancies.

- Patients with an anticipated survival of less than 3 months due to terminal non-infectious illnesses

- Those whose parents or guardians declined serial blood sampling

- Any child whose clinical team anticipated transfer to another facility

- Those who were physically unable to participate.

Local pediatric sepsis pathway

The hospital implements a nurse-triggered electronic Sepsis Early-Warning System (SEWS) in the emergency department. Key steps are: 1) Recognition and first hour (ED): SEWS ≥ 4 prompts immediate senior review. Blood cultures and complete blood count are drawn before antibiotics. Broad-spectrum therapy is delivered within 60 min (third-generation cephalosporin ± vancomycin for community-acquired, piperacillin-tazobactam ± amikacin for healthcare-associated). 2) Resuscitation bundle: Isotonic crystalloid 20–40 mL/kg is infused over the first 3 h. Point-of-care lactate, glucose and electrolytes are measured; vasoactive drugs are started if fluid-refractory shock occurs. 3) Admission criteria: Children with pSOFA ≥ 6, need for vasoactive or invasive ventilation proceed directly to the 15-bed pediatric ICU (PICU). Stable children (pSOFA < 6) are admitted to a 12-bed high-dependency observation unit (HDU) within the general pediatric ward (nurse:patient = 1:3, continuous monitoring). 4) Serial monitoring (ward or PICU): CRP, PCT, IL-6, SAA, ESR and D-dimer are repeated at 72 h and Day 7. pSOFA is recalculated at the same time-points. Daily fluid balance, vasoactive-inotropic score and respiratory support level are documented. 5) Pathogen-directed de-escalation: Antibiotics are narrowed to culture-confirmed monotherapy within 72 h whenever susceptibilities allow, following local antimicrobial-stewardship guidelines. 6) Step-down or discharge: Transfer from PICU/HDU to the general ward requires pSOFA ≤ 2, lactate < 2 mmol/L and no vasoactive support for ≥ 12 h. Discharge criteria include afebrile status for 24 hours, oral intake > 60% of requirement and caregiver education.

Data collection

Upon admission (T0), demographics (age, sex, weight), clinical parameters (vital signs), and suspected infection sites (respiratory, abdominal, etc.) were recorded. Baseline blood samples were collected for CRP, PCT, IL-6, SAA, ESR, and D-dimer. Subsequent samples were drawn on Day 3 (T1) and Day 7 (T2), or at discharge if earlier. Information on interventions (antibiotics, vasopressors, mechanical ventilation), durations of hospital stay (LOS), and any complications was documented in standardized case report forms.

pSOFA was computed at admission (T0), 72 h (T1) and Day 7 (T2) using the validated pediatric adaptation of the SOFA score.19 For each time-point we assigned 0–4 points to six organ systems: respiratory (PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio), coagulation (platelet count), liver (total bilirubin), cardiovascular (mean arterial pressure and/or vasoactive-inotropic score), central nervous system (Glasgow Coma Scale), and renal (serum creatinine). When a laboratory or clinical value was missing at a scheduled time point and there was no previous abnormal value for that organ system, a score of 0 was assigned. This conservative rule has been used in prior pSOFA validation studies. The total pSOFA ranged from 0 to 24.

Biomarker sampling and laboratory methods

Each blood sample (2–3 mL) was collected from a peripheral vein and immediately transported to the hospital laboratory. Levels of CRP and D-dimer were measured by immunoturbidimetric assay, PCT was determined by chemiluminescence, IL-6 and SAA were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and ESR was analyzed by an automated analyzer. All assays followed manufacturer-recommended protocols, and results were expressed in standard units, with calibration and internal quality control checks performed daily to ensure assay reliability.

Statistical analysis

All data were entered into a secure electronic database and checked for completeness and accuracy. Descriptive statistics, including means ± standard deviations or medians (with interquartile ranges), were used to summarize continuous variables, while frequencies and percentages described categorical variables. Biomarker changes over time were analyzed by repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Friedman test, with post hoc pairwise comparisons if significant. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated to assess relationships between biomarker levels (or their changes) and pSOFA scores. Where relevant, logistic regression techniques were employed to identify independent predictors of prolonged LOS or ICU admission. To enhance clinical utility, we generated ROC curves for CRP, PCT, IL-6 and D-dimer against (i) admission pSOFA ≥ 4 and (ii) hospital stay ≥ 7 days. Optimal cut-offs were selected by the Youden index and reported with area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity and specificity. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Missing data: Biomarker measurements were complete at admission; 5% were missing at 72 h and 6% at Day 7 due to hemolysis or insufficient volume. We used pair-wise deletion for non-modelled correlations and restricted maximum-likelihood estimation for mixed-effects models, both of which are unbiased under a missing-at-random assumption. Sensitivity analyses with last-observation-carried-forward produced identical direction and significance.

Log-scale sensitivity analysis: Because plasma biomarker elimination approximates first-order (exponential) decay, we repeated all correlation and regression analyses using natural-log–transformed concentrations. The change over 7 days was calculated as Δln = ln(T2) – ln(T0) = ln(T2/T0). Spearman correlations with ΔpSOFA and multivariable linear models (adjusted for age, time-to-antibiotic < 60 min and early de-escalation) were fitted. Predictive performance for favorable outcome (Day 7 pSOFA ≤ 2) was compared with DeLong’s test.

Results

Patient characteristics

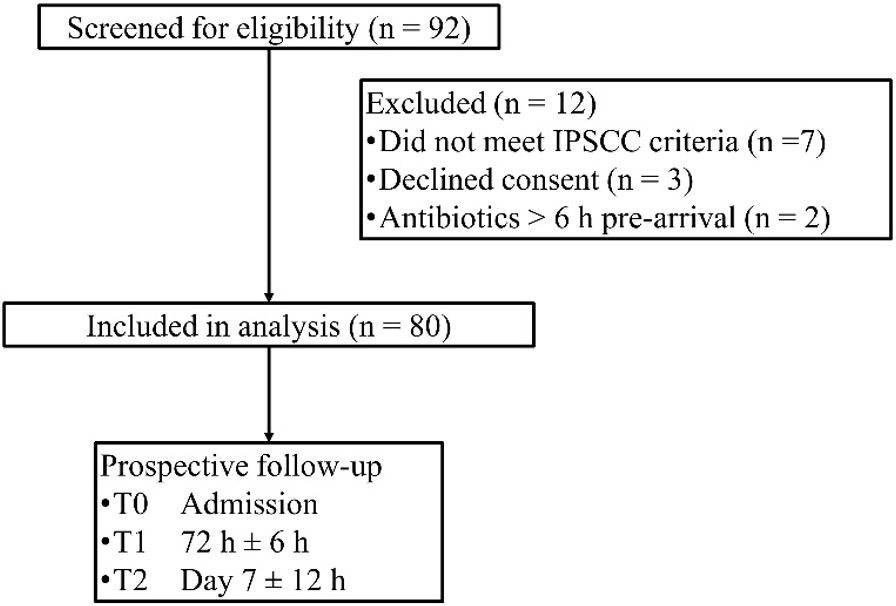

Eighty children fulfilled the enrolment criteria between March 2022 and June 2024 (Fig. 1). Their mean age was 6.2 ± 3.1 years (range 1–14); boys and girls were evenly represented. Only nine patients (11%) carried a significant underlying condition, most often congenital heart disease (5%). Respiratory (38%) and abdominal (25%) infections dominated the case-mix, and a microbiological pathogen was identified in 78% of episodes. Median time from symptom onset to hospital arrival was two days and the mean admission pSOFA score was 3.8 ± 1.5, indicating largely mild-to-moderate organ dysfunction (Table I).

| GI, gastrointestinal; IQR, interquartile range; pSOFA, Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; SD, standard deviation. | |

| Table I. Baseline characteristics. | |

| Age (years), mean±SD (range) |

|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male |

|

| Female |

|

| Weight (kg), median (IQR) |

|

| Underlying conditions, n (%) | |

| Immunodeficiency |

|

| Congenital heart disease |

|

| Others (e.g., mild asthma) |

|

| Primary infection site, n (%) | |

| Respiratory |

|

| Abdominal / GI |

|

| Urinary tract |

|

| Others / Unknown |

|

| Pathogen identified, n (%) | |

| Bacterial |

|

| Viral |

|

| Fungal |

|

| Mixed / unknown |

|

| pSOFA score at admission |

|

| Time from symptom onset to admission (days), median (IQR) |

|

Baseline biomarker concentrations varied meaningfully by both pathogen and infection focus. Children with proven bacterial sepsis entered the hospital with CRP and PCT levels roughly twice those seen in viral cases, while admission IL-6 was highest in respiratory and abdominal infections but lowest in urinary-tract disease (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Management and global outcomes

Timely adherence to the institutional sepsis pathway yielded favorable short-term outcomes. Only eight children (10%) required PICU admission and two (2.5%) underwent brief mechanical ventilation (median 2 days). The median hospital stay was nine days (interquartile range, Q1-Q3: 7–10), and no deaths occurred (Table II). These figures confirm that the cohort largely represents early-recognized, lower-severity sepsis.

| IQR, interquartile range; ICU, intensive care unit | |

| Table II. Clinical management and outcomes. | |

| ICU admission, n (%) |

|

| Duration of ICU stay (days), median (IQR) |

|

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) |

|

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (days), median (IQR) |

|

| Length of hospital stay (days), median (IQR) |

|

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) |

|

Temporal kinetics of inflammatory biomarkers

All six biomarkers decreased significantly over the first week (p ≤ 0.015 for each). Median CRP fell by 69% (65 to 20 mg/L) and PCT by 71% (3.5 to 1.0 ng/mL). IL-6 showed the steepest drop —an 82% fall from 220 to 40 pg/mL— while ESR declined more modestly (32 to 24 mm/h). D-dimer reduction mirrored clinical improvement, halving from 1.8 to 0.8 mg/L (Table III).

| Table III. Biomarker levels at different time points. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarker |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Levels are presented as mean ± standard deviation, or median (interquartile range). CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IL-6, interleukin-6; PCT, procalcitonin; SAA, serum amyloid A. |

|||||

| CRP (mg/L) |

|

|

|

|

|

| PCT (ng/mL) |

|

|

|

|

|

| IL-6 (pg/mL) |

|

|

|

|

|

| SAA (mg/L) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ESR (mm/h) |

|

|

|

|

|

| D-dimer (mg/L) |

|

|

|

|

|

Pathogen stratification revealed broadly similar kinetic patterns: regardless of whether infection was bacterial, viral or mixed, median CRP and IL-6 fell by at least 50% and 60% respectively over seven days, with no statistically significant interaction (Supplementary Table S3), demonstrating that serial rather than single measurements are needed to gauge treatment response, irrespective of microbiological etiology.

Relationship between biomarkers and organ dysfunction

Higher CRP, PCT, IL-6 and D-dimer levels at admission correlated modestly with worse organ dysfunction (Spearman r = 0.40 – 0.55; all p ≤ 0.003). Conversely, larger seven-day declines in the same four biomarkers tracked closely with greater pSOFA improvement (r = –0.41 to –0.53; p ≤ 0.002). SAA decline showed a weaker but still significant relationship (r = –0.32, p = 0.008), whereas the ESR decline was not statistically significant (r = –0.18, p = 0.11) (Table IV).

| Table IV. Correlation of biomarker levels and changes with disease severity (pSOFA). | ||

|---|---|---|

| Biomarker decline Δ(T2–T0) |

|

|

| CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IL-6, interleukin-6; PCT, procalcitonin; pSOFA, pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; SAA, serum amyloid A. | ||

| CRP |

|

|

| PCT |

|

|

| IL-6 |

|

|

| D-dimer |

|

|

| SAA |

|

|

| ESR |

|

|

Importantly, neither pathogen category nor infection focus modified these biomarker-outcome relationships; all interaction p values exceeded 0.18 (Supplementary Table S4). Overall organ failure resolved quickly: mean pSOFA declined from 3.8 at admission to 2.9 at 72 h and 1.9 by Day 7 (Supplementary Table S5).

Biomarker profiles and length of hospital stay

Children discharged within one week started with lower CRP, PCT, IL-6 and D-dimer values than peers remaining beyond Day 7, and their biomarkers fell more steeply—e.g. a median IL-6 drop of 200 pg/mL versus 100 pg/mL in the prolonged-stay group (Table V). These biochemical differences translated into a median hospital stay of five versus ten days, underscoring the prognostic value of early trajectories.

| Table V. Association of admission biomarkers and their changes with length of hospital stay. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of hospital stay |

|

|

|

|

Changes in levels are presented as median (interquartile range). Δ, Change in; CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; PCT, procalcitonin. |

|||

| CRP at T0 (mg/L) |

|

|

|

| ΔCRP (T2–T0) |

|

|

|

| PCT at T0 (ng/mL) |

|

|

|

| ΔPCT (T2–T0) |

|

|

|

| IL-6 at T0 (pg/mL) |

|

|

|

| ΔIL-6 (T2–T0) |

|

|

|

| D-dimer at T0 (mg/L) |

|

|

|

| ΔD-dimer (T2–T0) |

|

|

|

Diagnostic performance and sensitivity analyses

Natural-log transformation confirmed that larger relative (percentage) falls in CRP, PCT, IL-6 and D-dimer remained robustly associated with ΔpSOFA after adjustment for age, time-to-antibiotic and early de-escalation (Supplementary Table S6).

Receiver-operating-characteristic analysis identified pragmatic admission cut-offs —CRP ≥ 60 mg/L, PCT ≥ 3 ng/mL, IL-6 ≥200 pg/mL and D-dimer ≥1.5 mg/L— that predicted either pSOFA ≥4 or hospital stay ≥7 days with AUCs between 0.75 and 0.86 (Supplementary Table S7). Combining the admission thresholds with a ≥50% fall in IL-6 or PCT by 72 h yielded a composite C-statistic of 0.91 for ICU admission or prolonged stay, suggesting a practical two-step algorithm for early risk stratification.

Discussion

In our cohort of children with moderate sepsis, concentrations of all six biomarkers—CRP, PCT, IL 6, SAA, ESR, and D dimer—declined significantly during the first week of hospitalization. Higher baseline levels correlated with greater disease severity, while larger week long reductions were associated with shorter hospital stays and fewer ICU admissions.

Our data corroborate earlier pediatric studies: CRP, PCT, IL 6 and the remaining biomarkers fell sharply between admission and Day 7, and higher initial levels signaled greater disease severity.20-22 Although these analytes are standard in adult sepsis, developmental differences alter their kinetics and diagnostic thresholds; adult cohorts therefore require different cut offs.23,24 Direct comparisons confirm distinct temporal profiles of biomarker elevation in children, highlighting the need for age adjusted criteria.25 Pediatric series also report higher ICU admission rates and more frequent acute kidney injury than adult counterparts.26 The concordance of our findings with child focused investigations strengthens the evidence that PCT, in particular, is a sensitive marker for early diagnosis and prognosis in pediatric sepsis.16,27,28 Beyond classical inflammatory markers, a 2025 study from our region showed that plasma thiol/disulfide imbalance—a surrogate of oxidative stress—distinguishes septic from non septic PICU patients and independently predicts organ failure.29 Integrating such redox indices with the cytokine acute phase panel we report could further refine early risk assessment.

IL 6 peaked at admission and showed the strongest correlations with both pSOFA scores and length of stay. A prospective PICU study recently identified an IL 6 threshold of 178 pg/mL that predicted new onset multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) with 97% sensitivity.30 Mechanistically, this early cytokine surge activates the canonical Janus kinase / signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK/STAT3) pathway, amplifying hepatic acute phase protein synthesis and promoting endothelial injury, thereby predisposing patients to coagulopathy.31 PCT rose rapidly in our cohort as well but normalized sooner than CRP, a kinetic profile consistent with the BATCH randomized trial, where a PCT guided algorithm safely shortened intravenous antibiotic exposure compared with CRP based usual care.32 The slower decline of CRP reflects its IL 6–dependent hepatic production and clearance dynamics.33 SAA exhibited the highest admission spike yet maintained a prolonged plateau in children with extended hospitalization, mirroring evidence that high affinity binding to HDL stabilizes circulating SAA and delays catabolism.34 Finally, persistently elevated D dimer through Day 3 independently predicted longer stays, echoing a 2025 pediatric study that linked raised D dimer to micro coagulopathy and MODS.35 Concurrently, an elevated lactate/albumin ratio (LAR) predicted a 28 day mortality in hospitalized children with nosocomial infection.36 Because LAR reflects metabolic perfusion rather than inflammation, combining it with our inflammatory biomarkers could yield a more holistic bedside risk score.

The pronounced, time dependent declines in our biomarker panel illustrate the superiority of serial measurements over single snapshots: real time data enable earlier risk stratification and timelier therapeutic adjustments.12,14 Children whose CRP or PCT levels remain elevated, or fall only slowly, may therefore require closer surveillance or intensified support, a strategy reinforced by threshold based algorithms that individualize care according to biomarker trajectories.8,37,38 Embedding these trends into routine protocols allows clinicians to judge antibiotic response more accurately and to detect complications earlier, an approach now increasingly advocated for pediatric units, particularly those with constrained ICU capacity.39-42 Collectively, our findings support dynamic biomarker monitoring as a cornerstone of personalized management, with the potential to improve outcomes in children with mild to moderate sepsis.

Pediatric mortality prediction still relies largely on physiology‐based scores such as Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) III/IV, Pediatric Index of Mortality (PIM) 3 and Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction (PELOD) 2, each calculated from the worst values in the first 24 h after PICU admission and each demanding a substantial laboratory and monitoring footprint.43-46 In high resource settings PRISM III/IV discriminates mortality with an AUC around 0.8447; Chinese validation work reported a slightly lower AUC of 0.76 for PRISM IV but a comparable 0.80 for PELOD 244, underscoring real world variability. The newer pSOFA, which adapts SOFA thresholds for age, requires similar data volume yet achieved an AUC of 0.82 and out performed SIRS in multicenter Chinese cohorts.48 Within our early recognition, ward based cohort the median admission pSOFA was 4 and fell to 2 by Day 7, mirroring the moderate severity case mix described in those national studies. Importantly, the two step kinetic rule we propose (a four marker admission panel plus IL 6 or PCT decline by 72 h) predicted ICU stay or prolonged LOS with a C statistic of 0.91, doing so before the 24 h data window that PRISM/PIM/PELOD require. Because the kinetic rule relies on assays already drawn for routine care, it offers a rapid, low cost triage adjunct that can flag low risk responders for early de escalation or identify children whose physiology has yet to deteriorate enough to trigger the traditional scores. Future multicenter work should test whether combining ΔpSOFA with this biomarker trajectory further boosts discrimination across the full spectrum of pediatric sepsis severity.

This was a single-center study conducted in a tertiary referral hospital; results may not apply to district hospitals or low-resource settings. Our cohort was drawn exclusively from a high-dependency observation unit that sits between the emergency department and the PICU. Although this model is increasingly common in tertiary centers, it is not universal. The resulting case-mix (moderate severity, zero mortality) may therefore under-represent the sickest pediatric sepsis phenotypes. Prospective validation in higher-acuity settings will be essential before our two-step biomarker algorithm can be generalized. The total sample size limited power for subgroup analyses, particularly the fungal subgroup. We enrolled patients under the 2005 IPSCC definition; although 94% also met the 2023 Phoenix criteria on admission, future studies should adopt Phoenix criteria prospectively. We adjusted for time-to-antibiotic and early de-escalation, but could not control for all potential confounders such as cytokine-directed therapies because none were used. Finally, advanced biomarkers like presepsin and pro-adrenomedullin were not measured; their additive value remains unknown.

In this prospective cohort of 80 children with early-recognized sepsis, four readily available admission biomarkers —CRP, PCT, IL-6, and D-dimer— identified the sickest quartile (pSOFA ≥4) with an AUC of 0.84. Fall in IL-6 or PCT within 72 h predicted rapid organ recovery with 85% sensitivity and 78% specificity. The combination of these admission cut-offs plus the 72-h reduction index achieved a C-statistic of 0.91 and a negative-predictive-value of 0.92 for ICU admission or length-of-stay ≥ 7 days. Taken together, this two-step algorithm can (i) support early de-escalation or shortening of antibiotic courses in low-risk responders, (ii) flag non-responders who may need escalation or adjunctive therapies, and (iii) provide an objective criterion for safe transfer from high-dependency care to the ward or for hospital discharge.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University (date: 08.06.2021, number: yz202134).

Source of funding

The authors declare that the study is supported/funded by Maternal and Child Health Research Project of Jiangsu Province, grant number: F202071; Maternal and Child Health Outstanding Talent Project of Jiangsu Province, grant number: SWBFY 2021-9.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Bracken A, Lenihan R, Khanijau A, Carrol E. The aetiology and global impact of paediatric sepsis. Curr Pediatr Rep 2023; 11: 204-213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40124-023-00305-3

- Vaughn LH. Sepsis. In: Pediatric Surgery. Cham: Springer; 2023: 85-95. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81488-5_8

- Plunkett A, Tong J. Sepsis in children. BMJ 2015; 350: h3017. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h3017

- Molloy EJ, Bearer CF. Paediatric and neonatal sepsis and inflammation. Pediatr Res 2022; 91: 267-269. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01918-4

- Wheeler DS. Introduction to pediatric sepsis. Open Inflamm J 2011; 4: 1-3. https://doi.org/10.2174/1875041901104010001

- Wheeler DS, Wong HR, Zingarelli B. Pediatric Sepsis - Part I: “Children are not small adults!”. Open Inflamm J 2011; 4: 4-15. https://doi.org/10.2174/1875041901104010004

- Esposito S, Mucci B, Alfieri E, Tinella A, Principi N. Advances and challenges in pediatric sepsis diagnosis: integrating early warning scores and biomarkers for improved prognosis. Biomolecules 2025; 15: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15010123

- Leonard S, Guertin H, Odoardi N, et al. Pediatric sepsis inflammatory blood biomarkers that correlate with clinical variables and severity of illness scores. J Inflamm (Lond) 2024; 21: 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12950-024-00379-w

- Sumra B, Abdul QS. Pediatric sepsis: early detection, management, and outcomes - a systematic review. Int J Multidiscip Res 2020; 2: 1-15. https://doi.org/10.36948/ijfmr.2020.v02i06.12104

- Whitney JE, Silverman M, Norton JS, Bachur RG, Melendez E. Vascular endothelial growth factor and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor as novel biomarkers for poor outcomes in children with severe sepsis and septic shock. Pediatr Emerg Care 2020; 36: e715-e719. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001638

- Z Oikonomakou M, Gkentzi D, Gogos C, Akinosoglou K. Biomarkers in pediatric sepsis: a review of recent literature. Biomark Med 2020; 14: 895-917. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm-2020-0016

- Lanziotti VS, Póvoa P, Soares M, Silva JR, Barbosa AP, Salluh JI. Use of biomarkers in pediatric sepsis: literature review. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 2016; 28: 472-482. https://doi.org/10.5935/0103-507X.20160080

- Wang X, Li R, Qian S, Yu D. Multilevel omics for the discovery of biomarkers in pediatric sepsis. Pediatr Investig 2023; 7: 277-289. https://doi.org/10.1002/ped4.12405

- Downes KJ, Fitzgerald JC, Weiss SL. Utility of Procalcitonin as a biomarker for sepsis in children. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 58: e01851-e01819. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01851-19

- Silman NJ. Rapid diagnosis of sepsis using biomarker signatures. Crit Care 2013; 17: 1020. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13137

- Zhu S, Zeng C, Zou Y, Hu Y, Tang C, Liu C. The Clinical Diagnostic Values of SAA, PCT, CRP, and IL-6 in Children with Bacterial, Viral, or Co-Infections. Int J Gen Med 2021; 14: 7107-7113. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S327958

- Boenisch S, Fae P, Drexel H, Walli A, Fraunberger P. Are circulating levels of CRP compared to IL-6 and PCT still relevant in intensive care unit patients? Laboratoriumsmedizin 2013; 37. https://doi.org/10.1515/LABMED-2013-0029

- Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A; International Consensus Conference on Pediatric Sepsis. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2005; 6: 2-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PCC.0000149131.72248.E6

- Matics TJ, Pinto NP, Sanchez-Pinto LN. Association of organ dysfunction scores and functional outcomes following pediatric critical illness. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2019; 20: 722-727. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000001999

- Tyagi N, Gawhale S, Patil MG, Tambolkar S, Salunkhe S, Mane SV. Comparative analysis of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin as biomarkers for prognostic assessment in pediatric sepsis. Cureus 2024; 16: e65427. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.65427

- Kumar V, Neelannavar RV. Serum levels of CRP and procalcitonin as early markers of sepsis in children above the neonatal age group. Int J Contemp Pediatr 2019; 6: 411-415. https://doi.org/10.18203/2349-3291.IJCP20190037

- Murthy GRR, Pradeep R, Sanjay KS, Kumar V, Sreenivas SK. Acute-phase reactants in pediatric sepsis with special reference to C-reactive protein and procalcitonin. Indian J Child Health 2015; 2: 118-121. https://doi.org/10.32677/IJCH.2015.v02.i03.005

- Onyenekwu CP, Okwundu CI, Ochodo EA. Procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and presepsin for the diagnosis of sepsis in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 4: CD012627. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012627

- Aneja RK, Carcillo JA. Differences between adult and pediatric septic shock. Minerva Anestesiol 2011; 77: 986-992.

- Marassi C, Socia D, Larie D, An G, Cockrell RC. Children are small adults (when properly normalized): transferrable/generalizable sepsis prediction. Surg Open Sci 2023; 16: 77-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sopen.2023.09.013

- Stanski NL, Gist KM, Hasson D, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of children and young adults with sepsis requiring continuous renal replacement therapy: a comparative analysis from the Worldwide Exploration of Renal Replacement Outcomes Collaborative in Kidney Disease (WE-ROCK). Crit Care Med 2024; 52: 1686-1699. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000006405

- Baldua V, Castellino N, Kadam P, Avasthi B, Kabra N. Is procalcitonin a better option than CRP in diagnosing pediatric sepsis? RGUHS J Med Sci 2016; 6: 73-78. https://doi.org/10.26463/rjms.6_1_11

- Plesko M, Suvada J, Makohusova M, et al. The role of CRP, PCT, IL-6 and presepsin in early diagnosis of bacterial infectious complications in paediatric haemato-oncological patients. Neoplasma 2016; 63: 752-760. https://doi.org/10.4149/neo_2016_512

- Arı HF, Arı M, Ogut S. Oxidative stress and anti-oxidant status in children with sepsis. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 2025; 26: 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-025-00895-2

- Mohamed Said Abdelfattah WA, Hafez MZ, Ahmed ME, et al. Interleukin (6, 10): can be used as a prediction tool for multiple organ dysfunction syndrome in critically ill pediatric patients? Journal of Clinical Pediatrics and Mother Health 2024; 2: 019.

- Hirano T. IL-6 in inflammation, autoimmunity and cancer. Int Immunol 2021; 33: 127-148. https://doi.org/10.1093/intimm/dxaa078

- Waldron CA, Pallmann P, Schoenbuchner S, et al. Procalcitonin-guided duration of antibiotic treatment in children hospitalised with confirmed or suspected bacterial infection in the UK (BATCH): a pragmatic, multicentre, open-label, two-arm, individually randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2025; 9: 121-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(24)00306-7

- Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Invest 2003; 111: 1805-1812. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI18921

- Sack GH. Serum amyloid A - a review. Mol Med 2018; 24: 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10020-018-0047-0

- Shrikiran A, Palanichamy A, Kumar S, et al. D-dimer as a marker of clinical outcome in children with sepsis: a tertiary-care experience. Journal of Comprehensive Pediatrics 2025; 16: e152358. https://doi.org/10.5812/jcp-152358

- Arı HF, Keskin A, Arı M, Aci R. Importance of lactate/albumin ratio in pediatric nosocomial infection and mortality at different times. Future Microbiol 2024; 19: 51-59. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb-2023-0125

- Alder MN, Lindsell CJ, Wong HR. The pediatric sepsis biomarker risk model: potential implications for sepsis therapy and biology. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014; 12: 809-816. https://doi.org/10.1586/14787210.2014.912131

- Wong HR. Pediatric sepsis biomarkers for prognostic and predictive enrichment. Pediatr Res 2022; 91: 283-288. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01620-5

- He RR, Yue GL, Dong ML, Wang JQ, Cheng C. Sepsis biomarkers: advancements and clinical applications-a Narrative review. Int J Mol Sci 2024; 25: 9010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25169010

- Smith KA, Bigham MT. Biomarkers in pediatric sepsis. The Open Inflammation Journal 2011; 4(Suppl 1-M4): 24-30. https://doi.org/10.2174/1875041901104010024

- Iragamreddy VR. Innovations in pediatric sepsis management: from biomarkers to bedside monitoring. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 2025; 24: 38-39. https://doi.org/10.9790/0853-2401013839

- Schuetz P, Plebani M. Can biomarkers help us to better diagnose and manage sepsis? Diagnosis (Berl) 2015; 2: 81-87. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2014-0073

- Arı HF, Reşitoğlu S, Tuncel MA, Şerbetçi MC. Comparison between mortality scoring systems in pediatric intensive care unit: reliability and effectiveness. Pamukkale Med J 2024; 17: 664-673. https://doi.org/10.31362/patd.1479595

- Zhang Z, Huang X, Wang Y, et al. Performance of three mortality prediction scores and evaluation of important determinants in eight pediatric intensive care units in China. Front Pediatr 2020; 8: 522. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.00522

- Angurana SK, Dhaliwal M, Choudhary A. Unified severity and organ dysfunction scoring system in pediatric intensive care unit: a pressing priority. Journal of Pediatric Critical Care 2023; 10: 181-183. https://doi.org/10.4103/jpcc.jpcc_50_23

- Zhang L, Wu Y, Huang H, et al. Performance of PRISM III, PELOD-2, and P-MODS scores in two pediatric intensive care units in China. Front Pediatr 2021; 9: 626165. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.626165

- Shen Y, Jiang J. Meta-analysis for the prediction of mortality rates in a pediatric intensive care unit using different scores: PRISM-III/IV, PIM-3, and PELOD-2. Front Pediatr 2021; 9: 712276. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.712276

- Liu R, Yu ZC, Xiao CX, et al. Different methods in predicting mortality of pediatric intensive care units sepsis in Southwest China. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 2024; 62: 204-210. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112140-20231013-00282

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.